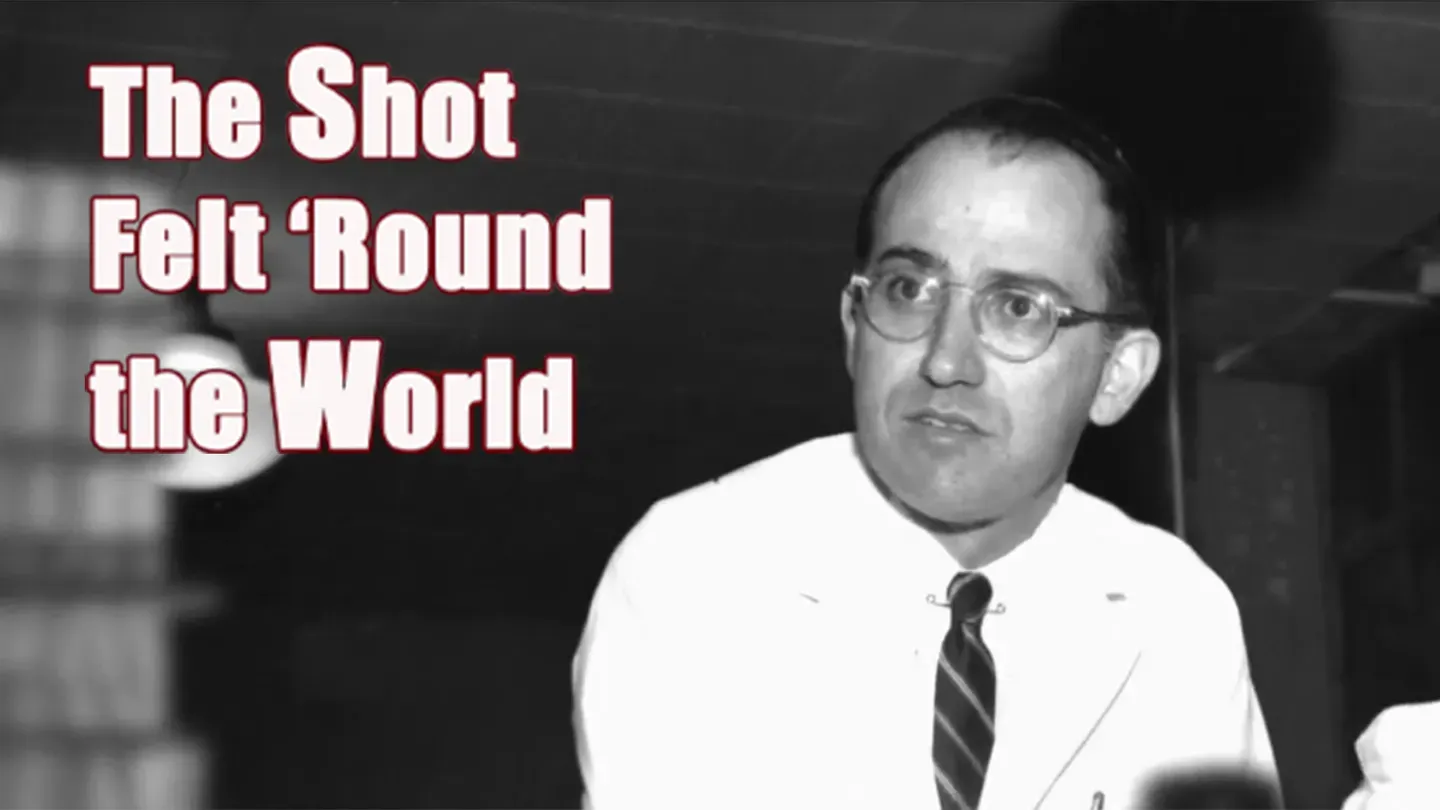

The Shot Felt 'Round the World

Special | 57mVideo has Closed Captions

How Dr. Jonas Salk and his team developed a vaccine that saved the lives of millions.

Polio held 20th century Europe and America in a state of terror — a virus that sought out mainly children each summer season. Pools and movie theaters became arenas of fear that this crippling and fatal disease would leave many in a dreaded "iron lung." A then-unknown Dr. Jonas Salk and his team would develop a vaccine that would save the lives of millions.

The Shot Felt 'Round the World: How the Polio Vaccine Saved the World is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television

The Shot Felt 'Round the World

Special | 57mVideo has Closed Captions

Polio held 20th century Europe and America in a state of terror — a virus that sought out mainly children each summer season. Pools and movie theaters became arenas of fear that this crippling and fatal disease would leave many in a dreaded "iron lung." A then-unknown Dr. Jonas Salk and his team would develop a vaccine that would save the lives of millions.

How to Watch The Shot Felt 'Round the World: How the Polio Vaccine Saved the World

The Shot Felt 'Round the World: How the Polio Vaccine Saved the World is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

(dramatic music) ♪ (projector clicking) ♪ (clicking stops) (dark music) ♪ (Paul) During the past century, we have increased our lifespan by 30 years.

Most of that increase is due to vaccines.

Before vaccines, pertussis, or whooping cough, routinely killed 8,000 people a year, mostly children.

Rubella, or German measles, would cause birth defects in as many as 20,000 children every year.

Measles would commonly cause between 500 and a thousand to die every year.

Diphtheria was the most common killer of teenagers.

All this before vaccines.

But I think you could argue that no vaccine captured, I think, the emotions certainly of the American public as much as the polio vaccine did.

I mean, you looked at these children walking down the street as if they had gone to war.

I mean, it was as if they were veterans of a foreign war, and it was young children.

I think it was just a very, very emotional disease for this country.

(soft music) ♪ (President Eisenhower) Dr. Salk, before I hand you this citation, I have no words in which adequately to express the thanks of myself, all the people I know, and all 164 million Americans, to say nothing of all the other people in the world that will profit from your discovery.

I am very, very happy to hand this to you.

(flashbulb popping) (somber music) ♪ (horns honking) ♪ (shouting) ♪ (David) When we look back upon polio today, you look back upon what was really a summer plague.

It came every year.

It came like locusts.

And newspapers would have almost baseball box scores of the numbers of kids who would come down with it in that week.

It would start around late May, and go up in June, and higher in July, and spike in August, and, then, by Labor Day, the summer plague would be over.

It would hit this kid and not this kid, and nobody knew why.

It would descend on Denver but not on San Francisco, and no one knew why.

All you knew was that every summer, thousands of very unlucky kids would come down with this insidious disease that usually left them incapacitated and often killed them.

(woman) People had all kinds of theories about it.

You shouldn't take your kids to a public pool.

Nobody should give birthday parties.

I mean, it was like a phantom enemy, this illness, and I was scared to death as a young mother.

(man) Polio would spread silently and then pick out its victim and continue to spread silently, pick out another victim.

(shouting) ♪ (man) It was known by then that it was virus disease, but there was no way to treat it.

And it wasn't really sure how it was transmitted.

People weren't sure.

(David) One of the great ironies of polio is that it appears to be a disease of cleanliness.

It begins in the United States in epidemic form early in the 20th century at the very time we are becoming increasingly antiseptic, germophobic.

Advertising is telling us that germs are very, very deadly, that we don't see them, but they are killers.

And the more cleanliness becomes kind of a way of life in the United States, the less likely young kids are to have immune systems that fight off disease easily.

There was a tremendous amount of myth and misinformation that surrounded the disease.

People thought that the disease was spread by cats.

They thought it was spread by fleas.

They thought it was spread by organ grinders' monkeys.

They thought that it was spread by bananas that had been imported from South America.

They thought that it could be cured by ox blood or sassafras or wood shavings.

There were just all kinds of myths.

(man) Every day when I went out to play, my grandmother would take a cloth bag with a piece of solid camphor, which they used to use it for mothballs, and she would put this little bag on a string and put it around my neck and send me out to play.

She was sure till the day she died that she had kept me from getting polio.

My mother, at that time, would actually not let me play with new kids.

The logic being that I had the germs of my older friends and there was no reason for me to get near new kids, because they may spread the polio germ.

And it was really that kind of fear that was felt by every parent in this country.

There was no prevention.

There was no cure.

There was no protection.

You could be a good parent, a bad parent, an indifferent parent, and you still had no way of protecting your child against polio.

♪ Polio is transmitted from person to person.

A child with polio infection comes in contact with another child and transmits that infection.

The virus reproduces in the mouth, it reproduces in the intestine, gets into the blood and invades the nervous system.

And what it does is it kills a particular cell in the nervous system called the anterior horn cell, and this cell tells the muscles what to do.

It's like cutting the wires to a light bulb.

The light goes off.

(cymbals fade) Well, I had a bad headache and went to the doctor the next day, and the following day, I collapsed.

And they figured I had polio and shipped me off to Municipal Hospital.

I got polio when I was 21 months old back in 1952.

(melancholic music) Our house was immediately quarantined.

A lot of people from the health department came to the house to interview my parents to find out where we've been, what we did, try to find out where we may have contracted the disease and everything, and meanwhile, we were all sent to Municipal Hospital.

♪ I started showing signs of paralysis.

And at that time, you got in an iron lung.

That was what happened when you went there and you had breathing problems.

And I was in an iron lung for approximately 11 days.

♪ (Sidney) That they couldn't swallow and get all the secretions in their throat and down into their lungs, and then they couldn't breathe, that was a deadly combination.

And so, they put 'em in an iron lung which would give positive and negative pressure to expand the chest so they could breathe.

That would pull air into the chest and push air out of the chest.

It was a nightmare.

It was a total nightmare both for the patients and for the doctors.

(woman) We would get these children coming up and they would be screaming, and the anxiety level was unbelievable.

You'd try to comfort them.

And how do you comfort a four- or five-year-old?

He didn't even have his teddy bear.

He could take nothing with him.

And I remember the faces on some of these kids, you know, in agony.

Just picture your own two-year-old, you know, can't breathe, and it's just dreadful.

(crying) (woman) Danny was probably, oh, my most favorite patient.

He was a little five-year-old and he had bulbar polio, so he was in a respirator.

I would tell Danny little jokes and read him stories and everything, and it was a beautiful relationship.

So I came on duty and I pick up my clipboard, and I look down and I don't see Danny's name, and I said to someone, I said, "Why don't I have Danny today?"

It was the loudest silence I ever heard in my life.

So I dropped my clipboard and I ran.

I'm sorry.

And I ran down to his respirator and it was empty.

(glockenspiel music) (rhythmic whooshing) ♪ (man) Polio, no treatment.

You just try to keep 'em alive with artificial breathing and physical therapy, and, then, try to equip 'em with some kind of gear that would help them walk again if you managed to save their lives.

♪ (rhythmic whooshing) (piano music) ♪ (David) Really, when you talk about polio infantile paralysis, you must, in the United States, begin with FDR, with President Roosevelt.

He got it at the age of 39 in 1921 and spent the rest of his life really trying to find the cure and the prevention.

He never found the cure.

He died in 1945 still having polio.

But what Roosevelt did was to put together a voluntary organization that was absolutely extraordinary.

In the past, philanthropies are a few millionaires giving money and throwing it at some project.

What the March of Dimes did was to turn this on its head.

(conductor) One, two, one, two, three four!

(upbeat music) (announcer) Each year, his birthday was celebrated with mammoth parties on behalf of the March of Dimes.

♪ Back when it started it was called the Mothers March, and its goal was to collect money to do research to conquer children's diseases, and polio was its primary target.

The name was then changed to the March of Dimes because a dime was the currency at the time that was a meaningful contribution from a child.

(announcer) Fight polio tonight.

Let the marching mothers know you're waiting for them.

(man) I remember going out with my mother on the Mothers March, and you would go around the neighborhood, and if the light were on on the front porch, then I would go to the house and collect a little cardboard thing that had inserts for coins to go in.

And we would gather those and ship those literally to the White House.

(Lucille Ball) There are a lot of parents whose children are healthy and happy now who live in fear.

I know I do.

The fear, my friends, is polio.

(David) What made the March of Dimes such an extraordinary organization was that, for one thing, they used the latest techniques in advertising and public relations.

They got celebrities like Mickey Rooney and Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley and, I mean, I have a picture in a book of a very uncomfortable Richard Nixon pumping gas for polio.

(man) They interrupt the serials in the motion picture house.

"We will now have a collection of March of Dimes."

And all the kids go, "I want to see the movie!"

Upon the quarters and dimes and dollars that you give now in this theater depends the happiness of some child somewhere tomorrow.

(David) They also used poster children.

You know, "Give me your money and help me walk."

And it was dime by dime by dime.

Everyone would give whatever he or she could.

It would be a crusade involving tens of thousands of people, and you would really make it into a national crusade.

These were Americans pulling together.

And they were pulling together to some degree because this was a children's disease.

And having a visual disease where you saw leg braces and you saw crutches and you saw iron lungs was something that was simply intolerable to the American conscience, and they united as a people to do away with it.

(lively music) I like it!

(applause, cheering) (somber music) ♪ (Jonathan) I grew up in a family where there was a sense, you know, that my dad was a scientist and that he did science, and he actually would talk about how he used to really, as a child, pray that he could do something good for humanity.

♪ He chose research, and he said this throughout his life: "I chose to do research because I asked myself, 'What can I do that's gonna do the greatest good for the greatest number of people?'"

♪ (David) Jonas Salk is brought to the University of Pittsburgh from Michigan not to work on polio but to work on influenza.

And what Salk understands very early on is that, you know, you sort of go where the money is, and the money was coming from the National Foundation with very, very large grants for polio.

(Peter) My father had an opportunity to participate in the complete drudgery of the polio virus typing program.

And that's something that no budding scientist at the beginning of his or her career would want to take on, but this was an entree.

Here was a place he could get started.

I mean, the good news was that there was a philanthropical base that was gonna support him here.

The bad news was it was Pittsburgh which at the time was the backwater of science.

♪ Jonas Salk was enormously well-organized, he was very hard-working, and he basically could run a laboratory much as one would run a laboratory in industry.

He had a lot of people that worked for him, and he was very good at being able to do difficult and arguably boring tasks quickly and well.

And so, one of his original tasks was to try and determine how many different types of polio viruses there were, because if there were many types, then all of them would need to be included in a vaccine.

In order to do anything towards a vaccine, one had to make sure that there were only three types of polio.

They knew that there were three types, but what if there were more?

(man) It was essential.

I mean, prior vaccines may have failed because they didn't have a representative of the three types.

So, it requires an intense effort to collect meaningful information.

Then, you can analyze it and get meaningful results.

Dr. Salk and his research team were in the basement.

They were looking for the live polio virus.

And so, when a patient has to have a bowel movement, we would cover the bedpan with a sterile towel and run to the door.

And sitting out in the hall on wooden benches would be Pitt medical students.

Kind of cute, too.

And that was their primary job, was to grab that bedpan and have it down in the lab probably within a minute or two.

And that's where Dr. Salk isolated the live polio virus from a young male patient at Municipal Hospital.

(David) This was the job that prominent researchers, prominent virologists would not do.

This was a job that an Albert Sabin would give to a graduate student.

It was scut work.

It was hard work.

It was uninteresting work.

But what Jonas Salk intuitively understood was that it was the kind of work that would get him on the March of Dimes bandwagon.

He was the miracle worker in the white coat on the one hand, but he was also an incredibly hard-working, devoted scientist for whom people were willing to sacrifice.

And Jonas Salk at the University of Pittsburgh put together an extraordinary team of researchers.

And what Salk did was sort of direct this team and whip this team and move it in a single direction, and that direction was to put out a killed virus polio vaccine as quickly as possible.

(Jonathan) He very much inspired a level of loyalty and devotion in people.

People had a sense that they were doing something of value, that there was a higher purpose to what they were doing, and that was a tremendously powerful thing.

But when he was tracking down something, when something needed to be done, it had to be done.

And he really did not tolerate delays very well.

(man) He had recruited two professionals, Byron Bennett and Jim Lewis, who were already here.

Jim Lewis was doing all the monkey-- most of the monkey work.

Then Byron Bennett was in charge of the mouse work and the preparation of all the samples that came from the monkeys.

(man) We had our own animal colonies on the second floor.

We had rhesus monkeys and, then, later on, cynomolgus monkeys.

And by the way, we made all our own food for the monkeys.

That food was made in our basement.

It had vitamins and supplements that we purchased.

(woman) When we were on the night shifts, we knew exactly when we had one hour to go.

The monkeys would wake up at 6:00 a.m. and they would grab their food pans and they would clang 'em against the bars of their cages.

What a racket!

And we would look at each other and smile and say, "We have one hour to go."

You know, so we called it "monkey time."

(moody music) ♪ (Jonathan) Elsie Ward did the tissue culture work, and she was superb at it.

She could get cultures to live and transfer that other people couldn't.

And she was really one of these people that-- she kind of talked to them.

She had this relationship with her tissue cultures that nobody else did.

She was like a gardener.

The cells, they were personalities to her, they were like flowers.

She cultivated them, she nursed them, she took care of them.

You know, Elsie had the special touch.

Jonas Salk and his team had to figure out a way to take three types of polio virus and to kill it with formaldehyde, but to kill it in such a way that it could still be juiced up to trick your immune system into producing antibodies.

(Paul) What he showed was that if he took polio virus, an infectious, live, dangerous polio virus, at, say, a million infectious particles per teaspoon, that he could then treat it with formaldehyde at a certain temperature, at a certain level of acidity, at a certain concentration of formaldehyde, and that he could reproducibly over, say, three days, go from a million infectious particles to one infectious particle.

So he would have a millionfold reduction over a period of three days.

He then reasoned that if he continued to do that, he would have another millionfold reduction over the next three days and another millionfold reduction over the next three days.

So for all intents and purposes, he had completely inactivated the virus.

Now, you had to have faith in this because-- because although you could test to see whether there was a thousand infectious particles per dose or one infectious particle per dose, you can't really test to see whether there's one infectious particle in a million doses, 'cause you're not gonna test a million doses.

(whooshing) (hissing) (spirited music) ♪ (man) He was challenging medical orthodoxy.

All of the ordained ministers of virology said, "You have to have a live virus in the vaccine to stop polio."

And Jonas kept saying, "No, I think we can fake the body into manufacturing these protective antibodies by giving 'em killed vaccine.

Don't have to have to worry about a tamed virus going wild again."

He loved the idea.

It's like, God, if you can prevent people from getting a disease without putting them at risk, why not?

And it was, you know, there was a certain sort of humane spirit to it.

Salk suffered what were two experiences that occurred in the 1930s.

One was made by an NYU researcher named Maurice Brodie who took brains of monkeys that were infected with polio, ground them up, and treated it with formaldehyde.

By doing it that way, there were many polio virus particles which sort of hid in that brain tissue and, therefore, he really gave children a live, fully virulent polio virus as a vaccine which obviously had a tragic result.

There was another researcher named John Kolmer, who worked at Philadelphia General Hospital, who believed that you could take polio virus and weaken it with an agent called ricinoleate, which is derived from the castor bean plant.

That, too, was a horribly flawed concept and resulted in a horribly flawed vaccine that, too, caused polio in some children.

So this was the mid-1930s, and I think it cast a pall over polio research for a solid 20 years, because you knew that in the mid-1930s, there were researchers that gave a polio vaccine that caused polio.

(Peter) He was well aware of the early vaccine failures.

The first attempt with an inactivated polio vaccine killed kids.

So, the way was clear what not to do, in a sense.

Jonas was the one who fought all those outside battles.

He fought the immunization committee that was almost unanimously opposed to a killed vaccine with Sabin leading the charge.

(dramatic music) (Paul) Albert Sabin was the vaccine orthodoxy.

I mean, he had bought into the notion that the only way to make a polio vaccine or, frankly, any vaccine was to take a virus and weaken it.

And I think he pooh-poohed Salk because he felt that Salk's notion of taking a polio virus and completely inactivating it with formaldehyde as a way to make a lifelong vaccine was ridiculous.

(Jonathan) Once he understood it and saw that it was right, he figured, well, that was good enough.

Everybody else should understand it.

He used to tell a story of when he was in medical school, somebody saying to him, "Dammit, Salk, can't you just do it the way everybody else does it?"

Um, and he couldn't.

It's like he couldn't.

We didn't have to really be stimulated very much by what was going on around us, because up on the third floor was the polio ward where they had all the iron lungs.

All you had to do was go and look in there and you didn't need much more incentive.

(woman) That's a very sobering experience, you know, just--just to have walked through all those iron lungs.

And the rocking beds, I think, were almost as impressive because to think that you just don't stop doing this all day, you know?

It was very sobering.

♪ (crying) (Peter) He saw what was needed.

He was aware of the suffering that was taking place.

He was aware of the fear.

He just had to get this done.

(man) He did not make people think that it's tomorrow.

And he kept saying, "We have to find out how many doses to give, how far apart.

There's a long road here yet."

But everybody was pushing him.

"Okay, we'll get it done faster."

(moody music) ♪ (gurgling) ♪ (man) After a while, it became seven days a week.

When we became convinced that we were on the verge of being able to solve this problem from the monkey data, just from the monkey data, this was high, high excitement.

I mean, it was kind of-- took you over.

(man) Jonas said to me at one time he felt like he was riding a horse and being whipped all the time 'cause O'Connor wanted to get it done, get it done.

Jonas says, "We're talking about a vaccine.

I don't even know if we have a vaccine.

I'm talking about an experimental preparation."

O'Connor said, "Jonas, you have a vaccine.

Now we got to use it.

There's no sense of saying it's five years away or ten years away.

Let's get moving and have it sooner rather than later."

(man) It was amazing even to us how rapidly things were going and how positive everything was turning out.

We were on a run that was unbelievable and couldn't be duplicated today.

We never could have worked the way we did.

The lab would've not passed inspection.

We would've had to have a much more elaborate-- elaborate setup.

(man) Our lab conditions were rather primitive.

We worked on open lab benches.

And on the lab benches, we put down towels which were soaked in mercuric chloride, so in case anything would drop onto 'em, the heavy metal in the mercury would destroy the virus.

We didn't have laminar flow hoods.

We didn't wear masks.

We didn't wear gloves.

There was no plastic.

Nothing was disposable.

(woman) The real volume was in what we called the kitchen, where all these test tubes had to be cleaned and sterilized.

And, I mean, it got to be the kitchen finally went to the basement and they had these huge centrifuges and all kinds of staff down there.

We made a lot of our own equipment even.

I made special types of pipettes to use.

Nothing more than a rubber tubing with a filter on the end of it that you could put in your mouth and suck the stuff up in the pipettes.

(woman) And you suck up on it and the fluid comes up in it, and then you stop it with your finger.

And then you put it in a test tube and lift your finger just enough until the right amount comes out.

(man) And if you're doing mouth pipetting with viruses, you may give an extra slurp, and you don't want that virus coming in your mouth.

So got up to one point and you expelled it.

(woman) You know, it didn't happen often that we sucked too hard.

If we did, we just ran to the sink and tried to wash it out as best we could and hope for the next two weeks.

Every time you have aches or pains, you figure, "Well, let's see, what's the incubation period of this and when do I start feeling it?"

But, uh, it's something you have to work with and that you're very careful all the time.

(exuberant music) ♪ (man) I'd bump into Jesse Wright.

Dr. Wright was the medical director at the D.T.

Watson Home.

And I knew that she was involved with kids and trying to restore their limbs.

And I used to say, "How are things going?"

She says, "Um, looking pretty good out our way."

She emphasized that.

And, suddenly, it hit me.

"On our way," that's where Salk is going to test the kids, D.T.

Watson Home.

But I couldn't confirm it with anyone.

Salk wouldn't tell me.

(man) Jesse Wright took a liking to me as they did at Municipal Hospital.

I must have been one heck of a kid.

But she took a liking to me, and I was one person in the first group of polio victims who they had tried the polio vaccine on to see how it would react to people who had already contracted polio.

(somber music) ♪ (man) And then I thought, "Oh, boy, this is great.

I'm gonna get the shot, I'm gonna be able to run around and walk again and go play ball."

The doctor said, "No, it's not gonna prevent what happened.

It's gonna prevent it happening to other people like your brother."

I said, "Fine."

(Peter) What he was looking for was what would happen to the antibody levels in those children who had already been exposed to that type of polio virus when they were injected with this experimental vaccine preparation.

(Paul) He showed that you can induce the immune response that clearly was a memory response, and that broke the orthodoxy.

It broke the orthodoxy.

Finally, it was established by the leading virologists at the time.

And he was, in that sense, a good decade ahead of his time, and he proved it, and still people didn't believe it.

(Peter) When my father saw that injecting these kids caused an increase in their antibody levels, that was the moment that the whole thing was done for him.

He knew that it was possible to immunize humans effectively with this inactivated preparation.

(David) Is he nervous when he begins human testing?

Of course he's nervous.

He literally goes to those places every night to see how the kids are doing.

But they had tremendous faith in Jonas Salk.

He was a father.

He tested the vaccine on himself.

He tested the vaccine on his children.

(man) I asked Donna, his wife.

She says, "Oh, yeah, he gave the kids the shots and they screamed."

There's a picture of me getting a vaccination that's clearly a setup shot.

I mean, it's just a wonderful, quintessential '50s photograph, but I'm there with a white shirt and a bow tie, and my father has this arm, staring intently as was his wont.

I mean, if he was involved in a procedure, it was like he was completely focused on that, giving me the injection.

My mother is gazing admiringly at him.

And I'm looking at the camera with this, you know, tears welling up in my eyes and my lower lip out just essentially saying, "Can somebody get me out of here?"

Doesn't anybody know I'm here kind of--kind of look.

I mean, it wasn't fair to go ask other people to take the vaccine when we didn't take it ourselves.

So we vaccinated one another.

We vaccinated our children before we went to the world.

Researchers invariably test it on their own children if they have children.

I tested our rotavirus vaccine on my then infant son, Will, in 1992 for a vaccine that was licensed in 2006.

I mean, so, it's not a leap for the scientists, because the scientists fully believe that this is safe and effective.

(spirited music) ♪ (whirring) ♪ (man) One of the big obstacles was to scale up what we were doing 'cause we were making home-brewed batches of vaccine.

And that's why, first of all, Bazeley was recruited, because he had experience in Australia making large-scale production of penicillin during the war.

(clanking) (man) We converted egg incubators, putting stainless steel shelves in there.

So they'd put a rotator on to get the shelves moving up and down.

We could put our big bottles on there to rock 'em.

(woman) He bought big jugs and big flasks, whereas, you know, we had used test tubes.

And they figured one monkey could supply six thousand doses of vaccine.

♪ So that was a lot because of the way the tissue was used and grown.

(David) After Salk ran successful tests in the Watson School, the March of Dimes felt that before he began his huge public health experiment, that he was gonna have to run a small study in the schools in surrounding Pittsburgh, and I think there was a tremendous pride that it was being done in their city with their money, involving people in their community.

(man) Once the word started getting around about some progress being made, there was no lack of volunteers.

I mean, parents were willing to turn their kids right over.

They were convinced long before Salk this is gonna work, this is it.

(uplifting music) ♪ (indistinct chatter) ♪ (David) And what is just amazing is how easy Salk found it not only to round up the 7,500 kids, but to round up pediatricians who were willing to give the shots, nurses who were willing to stand by, people who were willing to chauffeur these kids back and forth, record-keepers.

No one was being paid for this.

It was all done voluntarily.

And I think there was a sense in Pittsburgh that they were on the cusp of history.

(man) People responded by the hundreds, and there were accounts of people bringing their grandchildren in from out of state to get the vaccination because they wanted to make sure that they were protected.

(man) Dr. Salk would not tell the parents which school he was going to be at the next morning.

He says, "I want them to go to school like they're just going to class 'cause then they'd be uptight all night, they wouldn't sleep, the parents would be anxious."

He says, "And I don't want the parents there.

It's easier to give a kid a shot when the parent isn't standing over the kid's shoulder."

(woman) Well, they had us lined up and they called the name, and then they said it to you and you were supposed to verify it.

And, then, we were called into the area behind the screen and given a little Steiff bear to hold onto while we got the shot.

The needle was very long and very thick-looking and basically fearsome, which is why I spent a lot of time squeezing the bear and looking at the windows and the books.

(man) It was sort of a reddish fluid I remember.

And I remember trying to be brave and not crying.

And I remember how delighted my mother was.

My mother used to say, "Better you should cry than I should cry," and in essence, it sort of said it all.

This was viewed as a miracle.

(woman) We would help hold the children, calm them down.

And he would talk to them too.

He was very, very good with children.

And I think he was a comforting person.

(Jonathan) That concern, that relationship, that joy in some sense that he took interacting one-on-one with people, he really enjoyed when he got to do that.

That was really a quality that he had that showed everywhere.

My brother, Tommy, oh, he hated it.

They would try to corner him, and he'd run under tables, under chairs, screaming-- screaming his head off.

And he didn't care about the cookies and the orange juice.

He just didn't want to get a shot.

My sister, my oldest one was a fighter.

She fought them tooth and nail.

They had to actually put her on a prone cart and hold her down to give her the shot.

It turns out later that it wasn't the fear of the needle.

She thought they were giving her polio, what I had already had, and she didn't want it.

Parents were lining up their kids for a vaccine that no one could assure them was safe and no one could assure them it would work, but they had tremendous faith in Jonas Salk and his team.

They had tremendous faith in his humanity, and they had tremendous faith in his scientific ability.

It's not only a national crusade, it's really-- it's a humanitarian crusade, and generations of kids afterwards are gonna benefit from this.

(woman) He said he was glad that our kids could participate in the vaccine trials.

I was a nervous wreck, frankly.

I was scared to take them and scared not to take them, so I had to take them.

But, you know, we weren't sure what-- This whole thing was an experiment at that point, the vaccine.

(somber music) ♪ (Peter) I think with my father there were two parallel things going on: complete and absolute confidence in what he was doing.

I don't think there was a doubt in his mind.

And, yet, at the same time, there's always doubt, there's always the question, "Is it gonna work?"

(children shouting) (Paul) As a virologist and a researcher, it's interesting to watch how this plays out.

When you first start to work on a vaccine, you're trying to understand it.

You're trying to understand what part of the virus makes you sick, what part of the virus induces an immune response which protects you but not cause disease.

And now you think you've got it.

But, then, as--I think this is an old Chinese expression, you know, when the gods are really angry, they grant you your wish, you get your wish, which is now it's going to be tested in a big phase three trial.

And so you hold your breath.

♪ It's a tremendous leap.

Until you put them into children, you're not going to really know whether or not something is effective and, frankly, more importantly, safe.

And it's a testament to his courage and resolve that he could inoculate children with something that he knew started out as live, dangerous polio virus.

And although you can do studies in cells and mice, you never really know that's true until you put it in people.

(David) Jonas Salk, for all of his self-confidence, cannot possibly say that there is no chance of a kid getting polio from my vaccine.

Vaccines are always a matter of risk versus reward, and nothing is perfect.

Nothing is perfect.

♪ (woman) These were his neighbors' children he was sticking with this dead virus.

♪ That's not like inoculating someone in another continent.

♪ It was very real.

They were children who played Little League with his sons.

They were children whose parents he saw walking in the streets of Squirrel Hill or in Oakland, worked at the university.

So if he had harmed them, he would've been in a very, very difficult situation.

♪ (man) Mrs. Roosevelt, may I present this little bottle to you as a symbol of our hope that victory over infantile paralysis is almost here.

(cheering) (beeping) (announcer) It's time, America.

Time for Walter Winchell, the man who gives America the news.

Walter Winchell of the New York Daily Mirror and The Washington Post.

(Jonathan) On the eve of the field trials, Walter Winchell opened up his broadcast: "Mothers and fathers of America, they're preparing coffins for your children, because they're gonna be doing this experiment on them and some of your children are gonna die."

Walter Winchell was a yellow journalist of his time.

He believed, as he said, that the way to become famous is to throw a brick at people that are famous.

And that's what he did to Jonas Salk.

But I think that when Jonas Salk chose to make a vaccine that was funded by the March of Dimes, he signed up for being responsive to the American public.

And so, when people raised false concerns, I think it was his obligation to stand up and fend off that concern by trying to explain science to the public.

Not an easy thing, but I do think that was his obligation, and he saw that as his obligation.

(Jonas Salk) The studies that my associates and I have been doing at the University of Pittsburgh have indicated clearly that it is possible to induce antibody formation in children by suitable injections with a killed virus vaccine.

Uh, more than that, it appears that there are no harmful ill effects accompanying these inoculations.

That didn't hurt, did it?

-Okay.

-O'Connor said, "You have to do this.

In order to get your vaccine done, Jonas, there's certain things you need to do."

And, again, he was able and willing to do the necessary things to get things done, even if it wasn't exactly in his line of work.

Scientists are a reticent lot.

I mean, they--they generally avoid the light.

They work quietly in their rooms and try and come up with something new.

Salk was unique in the sense that he was put forward, I think, by a very large public relations group that was funded by the March of Dimes as a scientist who was going to help save our lives.

And I think scientists were jealous of that.

(Peter) When peers were critical, when there were attempts to derail what he wanted to do, I imagine that he would've had a sense of aggravation and frustration.

But my father had a sense of what was right in nature.

And it was that that he cleaved to.

What anyone else said, whatever dogma there was made absolutely no difference to him.

(rattling) (man) I remember asking Jule Youngner, I says, "Is this safe enough?"

Jule, he says, "Hey, this is like saying, 'Is the pregnant woman pregnant enough?'"

He says, "If it's safe, it's safe.

If she's pregnant, she's pregnant."

I says, "Okay.

I take your word for it."

(dramatic music) (man) In April 1954, field trials of the Salk polio vaccine begin in dozens of selected communities throughout America.

In the largest such test ever conducted, 1,800,000 children volunteer to participate.

The vaccine which has obsessed Jonas Salk for years now begins to pass out of his hands.

(Paul) When Thomas Francis was put in charge of the field trial that would ultimately become the largest field trial of a vaccine ever performed and I think will remain the largest field trial of a vaccine ever performed, there was a question about how to do it.

Can you do a trial where you give half the children, say, the vaccine and don't give vaccine to the other half and then watch what happens?

I mean, Salk believed in his vaccine, but the only way to know whether it was safe was to have a group that hadn't been inoculated.

Now, Salk didn't want these controls.

He thought it was morally reprehensible to give some kids the vaccine and knowingly withhold it from some others.

(man) The fact that he did agree to a placebo-controlled trial was a major, major plus in the evaluation, and that has become the gold standard for testing vaccines both for effectiveness and safety.

(indistinct chatter) ♪ (somber music) ♪ (man) In the early months of 1955, final tabulation of the Salk field trial results is being completed at the University of Michigan.

(man) A big announcement was gonna be made on April 12th.

So the pitch was going up in terms of press coverage of this as a seminal event in medical history.

(David) It takes a full year for the results to be analyzed.

Everybody is nervous.

Jonas Salk is confident but doesn't know.

No one tells him.

(man) This is Tuesday, April 12th, 1955, a day which may well mark the most significant event in all of medical history.

During the past few months, the results of last year's mass trial of Dr. Jonas Salk's anti-polio vaccine has been evaluated.

The world will very soon know whether the battle against the disease that has twisted hundreds of thousands of young bodies has been won.

(Peter) My father was deeply concerned.

When the field trial was being planned, it was decided that it was going to be necessary to add methylate, a preservative, to the vaccine.

Whereas my father knew the polio vaccine was gonna work, I don't know how confident he was that this large-scale field trial was going to come out with the results he had anticipated.

(Paul) Salk feared that that preservative would actually damage the vaccine viruses and render them less effective, and that really upset Salk.

I mean, he took this seriously.

I mean, it was called the Salk vaccine.

It wasn't just called the inactivated polio vaccine.

He knew his name was on it, and his heart was in it.

And he didn't want to watch what he had to watch, which was stand back and see the government allowing for a less effective vaccine.

♪ If the results from the observed study areas are employed, the vaccine could be considered to have been 60% to 80% effective against paralytic poliomyelitis.

There is, however, greater confidence in the results obtained from the strictly controlled and almost identical test populations of the placebo study areas.

On this basis, it may be suggested that vaccination was 80% to 90% effective against paralytic poliomyelitis.

(cheering) (Paul) And so, when Jonas Salk had his moment, he could've stepped up there and done what Neil Armstrong did, which was to say, "One step for man, one giant leap for mankind," something obviously that was practiced.

Jonas Salk had plenty of time to practice his speech.

He could've done that, but he was so obsessed with the notion of trying to make the best, perfect vaccine that all he could talk about were ways in which the vaccine could be made better.

It tells you a lot about the man, and I think that more than anything else tells you why he was so successful at making the vaccine because he was always restless, never satisfied, because like any scientist, he knew that there really isn't that moment of just sheer sort of joy that is unalloyed with pain or at least unalloyed with doubt.

(dramatic music) (shouting) (flashbulb popping) (indistinct chatter) ♪ (man) The guy gets off the elevator and he hits the runway, he never got into the room.

Everybody is yelling, "Give me one!"

A fella from the university service stands up on this table and he's just throwing them.

"Give me one, Lynn," or whatever his name was.

"It works, it works," they were yelling.

(Paul) There were newspaper reporters that ran to telephones to quickly get this as a front-page headline on probably every newspaper in this country.

This was his moment.

(David) It was a mob scene at Ann Arbor.

I can remember that day so well.

Television sets were set up in our school.

Kids ran out into the street.

School was called.

You know, factory whistles went off.

Church bells tolled.

People were crying.

It was in a way as if a war had ended, and in a way, a war had ended.

(cheering) (woman) It was like...

It was like something just being lifted, like you just thought, "Oh, you know, my God, I just can't believe that it's over.

I mean, it's over for millions and millions of children."

(woman) You can't describe it.

We were part of this, we helped, we helped, we helped.

And everybody was joyous and glad.

Dr. Wright, the staff.

The staff was ecstatic.

(woman) After that, the mailbags poured in.

I mean, we had mailbags like you wouldn't believe.

Letters and money.

(David) And movie offers began to come in.

Three studios were very interested.

And there are rumors that Marlon Brando was going to play Jonas Salk.

(applause) (uplifting music) ♪ When the vaccine was declared safe, potent, and effective, Jonas Salk became a national hero.

You know, he was on the cover of Time.

Newsweek called him "one of the greatest Americans."

He got the Congressional Medal of Freedom.

President Eisenhower invited him to the White House and actually broke down.

Few people had ever seen Ike do this.

He said, "I just don't have the words to thank you."

Ike was a grandfather.

This is a sign of how great medicine is and particularly how great American medicine is at this time.

It is an extraordinarily wonderful, optimistic moment.

Okay?

And there is reason to be proud.

(applause) (whistling) ♪ (rattling) (somber music) ♪ (tapping of typewriter keys) (clanking) ♪ When the vaccine became successful, Salk did what the best scientists do and what the most moral of them do and what the most humanitarian of them do, and he said, "This is a vaccine for the people.

You know, this is not a vaccine for my personal profit."

And he made the famous statement: "You can't patent the sun.

The sun is for the people.

This vaccine is science's gift to the people."

It was an extraordinary act.

(whirring) ♪ (Peter) It was an absolutely extraordinary moment in time, and there were so many streams that fed into this.

I think it really has to be remembered this wasn't the work of one person.

Everyone else in the laboratory, Dr. Youngner, Jim Lewis, Byron Bennett, Val Bazeley, these people were remarkable in terms of their flexibility, their dedication, their willingness just to roll up their sleeves, plunge in, do whatever was necessary to get this done.

(Jonathan) What happened with the vaccine involved a particular kind of optimism, a particular kind of understanding and belief in science, a particular kind of-- we have heroes.

We have people who can do this.

And I think my dad asked himself every day of the rest of his life, "Why can't this happen about other things?

Why can't this happen about poverty?

Why can't this happen about public health in a whole lot of ways?"

We have so many answers.

(Paul) Yeah, the Salk vaccine was unique.

It was unique in the sense that it was a decision really made by the American people to try and defeat a disease.

And so, everyone was part of this 'cause it was our vaccine.

And I do think it's in us.

I absolutely believe it's in us.

When you see moments like 9/11 happen or any tragedy happen, our instinct, I think, is always to act as a group.

And it's refreshing, I think, to--to see what we could do.

We'll never have a public health experiment like that again for all kinds of reasons.

I think we would hope, though, that we would have moments like this again.

The beauty of polio was that it was a disease that could be conquered by enormous human effort.

I mean, it is just a story of an extraordinary success, a success that involved tens of thousands of Americans working, really, overtime to find a way to fight a horrific disease.

And the beauty of Jonas Salk is that he was the man who sort of crystallized this.

♪ He is the people's scientist.

Whom do we remember?

Sigmund Freud, Albert Einstein, Jonas Salk.

It's perfect.

♪ (dramatic music) ♪ (uplifting music) ♪

The Shot Felt 'Round the World: How the Polio Vaccine Saved the World is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television