Reef Rescue

Season 48 Episode 4 | 54m 6sVideo has Audio Description

Scientists race to help corals adapt to warming oceans through assisted evolution.

If oceans continue to warm at the current pace, coral reefs could be wiped out by the end of the century. But scientists from around the globe are rushing to help corals adapt to a changing climate through assisted evolution.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Additional funding is provided by the NOVA Science Trust with support from Margaret and Will Hearst and Roger Sant. Major funding for NOVA is provided by the David H. Koch...

Reef Rescue

Season 48 Episode 4 | 54m 6sVideo has Audio Description

If oceans continue to warm at the current pace, coral reefs could be wiped out by the end of the century. But scientists from around the globe are rushing to help corals adapt to a changing climate through assisted evolution.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch NOVA

NOVA is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

NOVA Labs

NOVA Labs is a free digital platform that engages teens and lifelong learners in games and interactives that foster authentic scientific exploration. Participants take part in real-world investigations by visualizing, analyzing, and playing with the same data that scientists use.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Coral reefs have captured the human imagination for as long as we have ventured beneath the waves.

ALANNAH VELLACOTT: Towering, romantic, strong, resilient, but very ornate and, and delicate at the same time.

There really is nothing else like it.

NARRATOR: Beyond their beauty and brilliance, coral reefs support a quarter of all marine life and are crucial for ocean health and human survival.

But now these precious creatures are in crisis, as ocean heat waves are bleaching corals of all color and life.

♪ ♪ By the end of this century, coral reefs could be lost.

RUTH GATES: Can we help them?

Can we accelerate natural selection?

Can we accelerate adaptive rates?

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: On tropical reefs around the globe, scientists are fighting a desperate race against time.

♪ ♪ Unlocking the secrets of millions of years of coral evolution and trying to speed it up.

JULIA BAUM: If we are going to save coral reefs, we have to start intervening.

NARRATOR: Their ideas are new and experimental.

And for the first time, their daring research will be put to the test.

GATES: I think science and scientists are being asked to solve problems.

ANDREW BAKER: Honestly, we don't know whether it's going to work.

The risk of doing nothing is the risk of risking every reef on the planet.

NARRATOR: "Reef Rescue," right now on "NOVA."

♪ ♪ ANNOUNCER: Sailing a river through the heart of cities and landscapes with Viking brings you close to iconic landmarks, local life, and cultural treasures.

On a river voyage, you can unpack once and travel between historic cities and charming villages, experiencing Europe on a Viking longship.

Viking-- exploring the world in comfort.

Learn more at Viking.com.

♪ ♪ GATES: I will often describe it as my cathedral.

If you could imagine a cathedral with all of the stained-glass windows, all of that color is splashed across the landscape, with the fish darting in and out.

It's the place I go where I feel awed by the complexity of the architecture around me.

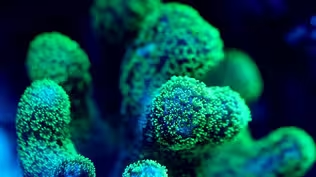

GREG ASNER: Coral reefs have been compared to tropical rainforests, and what I mean by that is the diversity of the species and how they're packed in together, how they create this kaleidoscope of color and function.

VELLACOTT: When I go underwater, each coral head is like its own little city.

When you get to a massive spur and groove system, it's like downtown Atlanta, super busy, bustling, characters everywhere, different sounds, clicking and popping and bubbling.

And it reminds you that we are all one piece of a community, or ecosystem.

NARRATOR: Corals appeared 500 million years ago.

They may look like rocks, but corals are in fact animals.

Each tiny coral creature is called a polyp.

The polyp is essentially a mouth with tentacles used to trap floating food, but most corals also have another source of nourishment.

GATES: Inside the cells of the animal, there is a tiny plant cell and they, as all plants do, are able to use the energy of the sun, capture it, to combine carbon dioxide and water into a small food molecule and oxygen.

NARRATOR: These microscopic plant-like organisms are algae.

The algae feed the coral animal, and the coral gives the algae a home.

It's a dynamic symbiotic relationship.

So much so that the algae are called symbionts.

♪ ♪ Reefs begin when coral polyps secrete a thin layer of calcium carbonate to create a skeleton.

Hundreds and hundreds of identical coral polyps create a colony.

And over thousands of years of growth, coral colonies build the reef.

So animal, vegetable, mineral.

That is what a coral is.

NARRATOR: Christmas Island is an atoll in the Pacific Ocean made entirely of coral.

Julia Baum is a Canadian marine biologist.

For more than a decade, she's studied the reef's unique ecosystem and the threats it faces.

It always feels great to be back.

It's a bit of a mix of emotions; there's, there's so much invested in every single trip.

Always a little bit of excitement about an adventure that's about to begin, and also maybe a little apprehension just to make sure, is everything going to go okay?

Hey!

(laughs) Hi!

I think that it's actually, I know it sounds crazy... And then I think that... but I think it's actually you're gonna, you're gonna drop there.

MAN: And that's... NARRATOR: It's Julia's first day out on the reef this year.

Oh, did you... NARRATOR: The team dives down to take stock of the coral.

(splashing) ♪ ♪ BAUM: When I first started doing research on the ocean, I had been so focused on sharks and fish, and at some point, I think I kind of looked down and saw the coral and realized, "Hey, the coral are the whole foundation of this ecosystem."

And if we're worried about this ecosystem, we really have to be worried about the coral themselves.

We have hundreds of corals tagged all around the island, and we take tiny tissue samples from them.

We can take the photos to identify individual coral colonies themselves and get a sense of who's there in the community.

A brain coral is one of the main types of corals that we've been working with.

There's also branching corals and flat corals, so lots of different shapes, and those are important because they provide different types of habitat for fishes.

NARRATOR: Each year, Julia and her team meticulously tag, sample, and photograph 40 plots of coral, building a timeline of how the reefs are changing.

During the 2015 and 2016 El Niño, water temperatures here increased by four degrees Fahrenheit.

The heat set itself down on this island and just got a chokehold on it, and it just kept going and going for ten straight months.

And what we saw was a complete ecological meltdown.

By the time we came back in March 2016, almost everything was dead.

It was like a graveyard.

It's just hard to believe that a whole island can die in less than a year.

(diver panting) SCIENTIST: How'd it go?

Okay?

Tough, a lot of stuff going on there.

I want to look at both of those dive slates and compare the corals, photo for all of them, tissue for all of them, and growth for some of them.

Yeah.

Okay.

BAUM (voiceover): It's pretty devastating, being down there, because I just remember that being my favorite site, and it just feels, like, how did this happen?

And even though, obviously, intellectually I know exactly what happened, but emotionally it still feels like... it's just really, um... it's a pretty sad remnant of what it was.

It's gone, really.

NARRATOR: Tropical reefs around the globe were severely impacted by the deadly ocean heatwave.

And scientists have been mobilizing-- led by the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology-- a research station perched on an island surrounded by coral reef.

Guiding this enormous effort is visionary scientist Ruth Gates.

(laughing) You have a couple of options: you move, you adapt, or you die.

Obviously corals are dying, they can't move, so their only option is to adapt.

NARRATOR: Corals have a natural ability to adapt to changes in their environment and have done so for millions of years.

But now, the oceans are heating up too fast.

GATES: So, can we help them?

Can we accelerate natural selection?

Can we accelerate adaptive rates?

NARRATOR: Ruth is a revolutionary thinker in a new area of coral science.

It's called assisted evolution.

GATES: It is our responsibility to take our science and activate things that can make a difference, try to solve the problem instead of just describe that it exists.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: And to take a closer look at the problems corals are facing, researchers use a powerful laser microscope to generate images of living corals.

(machinery whirs) (lens winding) Fluorescence highlights the algae partners in red.

This is a most beautiful coral.

It's completely healthy, it's showing, it's extending its polyps away from the skeleton.

Kind of out there, waving.

It's just dynamic and beautiful.

Each polyp looks like it's got a different personality and it's blowing me a kiss.

It's this one that's blowing me a kiss.

(laughs) (microscope lens winding) NARRATOR: But what happens to the symbiotic algae when waters warm?

GATES: This is actually a partially bleached coral.

It's starting to lose its symbionts.

You can see there's a lot more black space in between the corals.

NARRATOR: When heat stresses the corals, they expel their algae.

These dots of red are the plant cells that the animal has essentially spat out.

They're no longer serving the animal.

It's no longer moving anywhere near as dynamically.

It's kind of gone very quiet.

NARRATOR: Without the algae, corals lose their color.

And this is coral bleaching.

(waves lapping) (birds chirping) NARRATOR: Alannah Vellacott is a diver and coral restoration specialist who understands this problem firsthand.

They can always use a bit of fanning.

Oh, sorry, buddy.

I keep knocking you.

NARRATOR: Alannah works at Coral Vita, a coral farm in the Bahamas that grows corals to revitalize dying reefs.

VELLACOTT: Currently, 80 percent of corals are dead in the Caribbean.

That is especially sad and especially troubling because we cannot afford to lose our coral reefs.

NARRATOR: Reefs are highly diverse ecosystems.

Fish shelter, find food, and rear their young in their many nooks and crannies.

Fewer reefs means fewer fish, but it's not just the marine ecosystem that's at risk.

People depend on reefs for food and income.

(fishing reel winding) VELLACOTT: Bahamians are very intimately tied to our waters, because it is our livelihood.

Whether you work in a hotel, whether you're a dive operator, whether you're a fisherman, whether you just enjoy having a conch snack at the end of the day, we all depend on these coral reefs.

If the world continues to go in the direction that it's going in, ignoring what our reefs are trying to tell us, it very well is the end of our livelihoods here in the Bahamas.

NARRATOR: Bahamas and beyond, some three billion people rely on fish as a source of protein, and the overall economic value of reefs is estimated at tens of billions of dollars annually.

(car door closes) Almost 90 percent of the corals surrounding Christmas Island bleached, and Julia wonders if the reef and the biodiverse habitat it provides could be lost.

Okay, so I have 2015 loaded.

Mm-hmm.

This is just five months before the heat stress started to hit.

So, the reef is looking really healthy.

So then let's load the 2017 on top of that and take a look at that one overlaid.

Kind of shows how much the structure is breaking down.

Just-- all the height is eroding.

NARRATOR: Devoid of living corals, the reef is crumbling and falling apart.

BAUM: Oh, God, this is horrible.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Can a damaged reef regenerate?

(bubbling) Each year, Julia's team anchors new clay tiles to the reef and retrieves tiles from previous years.

Normally, baby corals will settle on these, and the team will document any signs of new growth.

BAUM: It feels like a waiting game to see-- is this gonna turn the corner and recover, or is it gonna decline and die?

(camera clicking) I still need the white light to look at it though.

(camera clicking) We have a baby coral from one of the degraded sites.

We hoped for it, but we didn't really expect it.

So, yeah, that's exciting.

NARRATOR: This first evidence of new life is a tentative sign of regeneration.

But how could this happen?

After bleaching, researchers feared the reef was lost.

BAUM: In the midst of all this devastation, we found a glimmer of hope.

NARRATOR: Julia discovered life among the ruins-- baby corals struggling to rebuild.

This meant some of the parent corals withstood the heat.

BAUM: The corals here had been sitting in essentially a hot water bath for ten months, so they had been stressed out more than any coral on the planet, and yet, here they were, looking perfectly healthy.

NARRATOR: Here, while water temperatures remained high, a small percentage of the corals recovered, making these the only corals ever observed to have been exposed to such extreme temperatures for so long and survive.

So, to me, this was almost like a miracle.

What is it that's so special, that's so unique about these corals that healed themselves while they were still under stress.

What is it about them?

NARRATOR: Why do some corals survive when others perish?

What is the secret of these super corals?

And what can we learn from these survivors to help save the rest?

(indistinct radio chatter) MAN: Traffic, traffic.

(indistinct radio chatter) NARRATOR: Greg Asner's Airborne Observatory is a custom-designed plane equipped to create a picture of how reefs are changing.

How many passes through here?

MAN (on radio): We're going to do... five more.

(radio chatter) NARRATOR: Using a spectrometer and LiDAR lasers, Greg can analyze the corals from above, measure their chemistry, and create a 3D image.

ASNER: This region here, in the pinks, that's the live coral.

These corals are all a mix of dead and live.

The system gives us a very unique view of coral reefs, an understanding of where the live coral is located.

That's really critical, especially nowadays where we're looking for surviving corals in literally... in a sea of a lot of dead coral.

Yeah, we're over the big island now.

Like many other reefs, they've gone through a lot of change.

(propellers humming) NARRATOR: The burning of fossil fuels has increased the concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide, raising the Earth's overall average temperature.

ASNER: You raise the total temperature of the planet and you've changed literally the fundamental heat flow over the earth's surface.

You're causing heat waves in the oceans.

You're causing droughts on land.

You're causing a rebalancing of the entire thermal portfolio or profile of the earth's system, and that's the thing that we're dealing with as biologists.

NARRATOR: These changes may have deadly consequences.

So Greg is taking his airborne research one step further... teaming up with Ruth Gates to find corals that are resistant to bleaching.

ASNER: We're going to be getting in the water to look at the corals that we flew over yesterday.

And this is key for linking the aircraft data to what's going on in the coral itself.

That's how we make the connection.

(splashing) NARRATOR: Underwater, Greg will use a small spectrometer specifically designed for diving.

♪ ♪ Tools in hand, Ruth and Greg set out to find the specific corals identified by the airborne observatory as survivors of heat stress.

(bubbling) They need to confirm that the data from the plane reflects the reality on the reef.

By monitoring the reef over several years, Ruth has already identified corals that have resisted bleaching.

And sure enough, Greg's spectral data from the air matches Ruth's observations underwater, bringing them one step closer to identifying super corals at a scale and speed previously unimaginable.

So, the dark brown coral in the bucket right now, we affectionately term "super corals," and we call them that because they are unaffected by the conditions or the stress that is causing other corals immediately adjacent to them to pale and whiten and show signs of very severe stress.

So once we can understand what is different between the super corals and the weak corals, our goal is to develop or breed more super corals that we can use to restore damaged reefs.

♪ ♪ (water churning) NARRATOR: Now Ruth's team prepares to breed the super corals that have survived bleaching events.

Corals here are spawning tonight and researchers will act as matchmakers.

GATES: If we've got a really good performer over here and over here, let's not leave it to chance that their eggs and sperm would meet.

Let's bring them together and make sure they do.

So that's accelerating a natural process, really having a slight human intervention to make sure we breed the best moving forward.

(indistinct chatter) NARRATOR: As night falls, Ruth's team prepares for one of the most phenomenal events in all of nature.

Each coral species spawns at a very specific moment, timed with seasonal temperatures and the moon.

GATES: Corals can sense the moon, and they will release their eggs and sperm within five minutes of a particular phase of the moon, it's an astonishing thing.

(boat motor humming) NARRATOR: Once spawning begins, it won't last long.

Researchers use red lights, so they won't disturb the corals' ability to sense lunar cues.

Then move it across... NARRATOR: The team must work quickly to collect the precious sperm and eggs.

(splashing) An entire year's work is on the line.

♪ ♪ Corals are fixed in place, so they release gamete bundles containing their egg and sperm into the water column.

These buoyant bundles rise towards the surface, creating an underwater blizzard where fertilization begins.

♪ ♪ The gametes from selected coral are caught in the nets.

Lids secured, researchers head back to the boat.

Yeah, we have everything!

NARRATOR: The team combines the coral gametes according to a predetermined plan, breeding them for their strengths.

(bucket contents shifting) (boat motor humming) Time will tell if tonight's efforts were successful, but past years of collecting, breeding, and observation have already paid off, as lab-reared "super corals" can tolerate warmer temperatures.

How do we move the needle and scale to many different places?

Because the corals that do well in Hawaii don't all live, say, in the Great Barrier Reef.

NARRATOR: In Australia, hopes are high that assisted evolution could help save one of the seven natural wonders of the world.

The Great Barrier Reef has been hit hard by successive ocean heat waves, resulting in severely bleached coral along its entire 1,400-mile length.

Researchers here are taking the next big step, moving assisted evolution out of the lab and into the ocean.

And there is no better place to prepare super corals for this journey than in the state-of-the-art National Sea Simulator.

Here, Ruth Gates' long-time collaborator, ecological geneticist Madeleine van Oppen, is soon to embark on a groundbreaking trial.

MADELEINE VAN OPPEN: Ruth and I met, I think maybe 2005.

I think the idea was already starting to happen that we should use the knowledge that we had gained over the past decades on how corals adapt and acclimatize, to actually harness those mechanisms to help corals evolve further.

NARRATOR: Researchers here can set the temperature and acidity levels of individual aquariums to match those predicted for the ocean in the years ahead.

And Madeleine is creating a new kind of super coral: a hybrid.

A hybrid is a cross between two entirely different species.

VAN OPPEN: Hybridization does happen in nature, in corals and also in other plants and animals, but it doesn't happen frequently.

NARRATOR: When it does, hybrids have proven to be more resilient.

VAN OPPEN: This is a hybrid coral that we've actually created in the lab in 2015, and actually we put it through seven months of exposure to future ocean conditions, so warmer and more acidified oceans, and it survived those conditions.

NARRATOR: Now that Madeleine has achieved success with lab-reared hybrids, she needs to find out if newborn hybrids can grow and survive in real ocean waters.

♪ ♪ To create these new hybrids, Madeleine needs eggs from one species and sperm from another.

There is no better time to gather these ingredients than when corals spawn.

VAN OPPEN: So, this cup is full of the bundles of eggs and sperm that are collected outside which I will now pour over this mesh.

And the mesh is of a size that the sperm will go through, and the eggs will stay on top.

NARRATOR: With egg and sperm from two selected coral species separated, Madeleine can now bring these together to create the hybrid.

Even though we have a fabulous sea simulator, it still is an aquarium and it's not exactly the natural environment, so we need to test those results, validate those results in the field.

NARRATOR: For the first time ever, these babies are headed to the Great Barrier Reef.

VAN OPPEN: The biggest challenge is the really high mortality we tend to see in the field.

NARRATOR: These lab-reared babies have never experienced real ocean waters before, and the transition could be deadly.

VAN OPPEN: We might get a cyclone that all of a sudden pulls down the water, or we might get a lot of cloud formation during summer that will reduce the amount of light.

NARRATOR: The baby corals grow on tiles and are transported on trays to a designated site alongside the reef.

VAN OPPEN: We really need to have these field results before the regulators will allow us to actually implement these interventions in reef restoration.

NARRATOR: After three months, scientists from Madeleine's lab oversee the infant hybrids' first checkup.

ANNIKA LAMB: So, right now we're cleaning the tiles, which we just brought up from the ocean, so that they'll be ready for the photographer to get a clean shot of.

KATE QUIGLEY: I'm just going through each tile, trying to find the babies, which are still quite small, they're kind of, adolescents, I guess you could say now, about six months old, and so we just find them, and then I circle them, we take a photo, and that allows us to look at survival, and then it also allows us to measure growth.

NARRATOR: There are more than a thousand tiles with different genetic combinations.

It will take over a week to examine and photograph every one individually.

(indistinct chatter) QUIGLEY: So we've just taken all these photos outside, so now we're going to start analyzing them, and the first thing we do is just look at alive or dead.

Yeah, so no... No pencil marks on this one.

Maybe try the next one?

QUIGLEY: I don't see anything on that one, some dead ones, yeah, long dead.

LAMB: Yeah.

QUIGLEY: A lot of dead guys.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Early observations are concerning.

Many of the baby hybrids did not survive the journey from lab to sea.

But hope is not lost.

There are more tiles to examine in the week ahead.

VAN OPPEN: Climate change has affected the Great Barrier Reef quite dramatically in recent years.

We lost half of the coral present.

As soon as populations start to lose genetic diversity, the capacity to adapt further and respond to environmental change also diminishes.

It can become a downward spiral very, very quickly.

GATES: Let's think about how we actually react instead of just watching our system die before our eyes and then asking ourselves 20 years from now, "God, I really wish I'd done something."

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: During the filming of this documentary, Ruth Gates is diagnosed with brain cancer.

Like the coral reef she loves, her life hangs in the balance.

♪ ♪ Laetitia Hedouin is a scientist who studied under Ruth Gates.

On the island of Mo'orea in French Polynesia, Laetitia is "conditioning" or "training" corals to survive ocean heat waves.

Her recent graduates are growing in this coral nursery.

HEDOUIN (speaking French): ♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Laetitia aims to train large quantities of corals to make them more resilient.

So her work begins in the crucial first hours of a coral's life.

HEDOUIN: NARRATOR: Laetitia will expose these coral embryos to increasing amounts of heat stress.

Like young athletes on a treadmill, they will be conditioned to become "super."

NARRATOR: The goal is to increase their thermal tolerance by subjecting them to an exercise regime similar to what they may experience in an ocean heat wave.

HEDOUIN: NARRATOR: The embryos have grown quickly into tiny larvae.

This is the only time in a coral's life that it will ever swim.

(rooster crowing) HEDOUIN: NARRATOR: Once settled, the coral polyp begins to grow.

Soon it should be moved to the coral nursery in Mo'orea's lagoon.

But now, Laetitia finds trouble brewing on the reef.

HEDOUIN: NARRATOR: An impending ocean heatwave threatens the reef, and her research.

NARRATOR: As the summer heat intensifies, so do warnings from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

About 1900 to present, that basically represents a degree Celsius of warming.

REPORTER: With one and a half degrees, 70 to 90 percent of coral reefs are lost, but at two it's virtually all of them.

It's very clear that half a degree matters.

I think this report is alarming, it should make us act.

IPCC and other reports now coming out are just getting to the level where they're saying, "Look, this is happening faster and, and more extreme than we thought."

The urgency of this cannot be overstated.

The changes are real, the changes are rapid, and they can be quite extreme.

NARRATOR: And if we lose reefs, there will be dramatic consequences.

(waves splashing) Coral reefs provide safe harbor for our coastlines.

They buffer waves, helping to prevent erosion, property damage, and loss of life.

So, if you look out just in front of the horizon, there's a line there, a line of, of, of waves, a line of foam, and that is the reef crest, and that is our first line of defense when it comes to storms and hurricanes.

NARRATOR: When natural ecosystems that protect coastlines are in poor condition, people are vulnerable.

(wind whipping) (water splashing) When Hurricane Dorian hit, it was the worst tropical cyclone on record to reach the Bahamas.

The damage was catastrophic.

VELLACOTT: So, September last year, the islands of Abaco and Grand Bahama were absolutely devastated by Hurricane Dorian.

Sixty percent of Grand Bahama was underwater, and thousands and thousands of people lost their homes.

Hundreds of people are still missing today.

My childhood home where my dad lives was completely destroyed.

For the first time I experienced what it was like to be a climate change refugee.

And as much as we'd like to think of climate change refugees as people of the future, the future is today.

It's happening right now.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: And what happened in the Bahamas could happen to coastal communities anywhere.

Billions of people live within 60 miles of a coastline.

♪ ♪ The east coast of Florida is lined with coral reefs that have protected people here for thousands of years.

But now, these reefs are crumbling.

♪ ♪ The Sustain Laboratory at the University of Miami is one of the few places in the world designed to measure the impacts of a Category 5 hurricane.

(wind whipping, water rushing) Here, Andrew Baker and his team are working to quantify how corals mitigate the impacts of extreme storms.

Is there any wind going on this?

MAN: Now there is, now there is, yeah.

BAKER: That's pretty good, it's breaking right on the coral.

Because of climate change, we're seeing rising seas, we're seeing more powerful storms, we're seeing storm surge and other kinds of flooding impacts.

Coral reefs have been shown to reduce wave energy in some cases by 94, 95 percent.

(water flowing) NARRATOR: Without reefs to protect its shoreline, storm surges could devastate Miami.

BAKER: How do we make coral reefs more climate ready, more climate tolerant, more thermally tolerant, and how do we protect our coastlines from the damaging effects of storms?

So, what we're trying to do is not only use coral reefs to build natural breakwaters, but make the very corals that we're using to build those reefs themselves more thermally tolerant.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Andrew and his team are trying to make reefs more climate-ready by helping corals switch their algae to ones that can take the heat.

The researchers use a technique called "controlled bleaching," attaching the corals to a raft, then raising them up toward the surface where they'll receive more sunlight.

After a few hot days under clear skies, the coral stress, eject their algae, and bleach.

And without the nourishment the algae provide, the corals will soon die.

But Andrew has a plan to save them from this fate... BAKER: This partnership between the coral and its algae dates back over a hundred million years.

We have different types of corals, but we also have many different types of algae, and in fact they can sometimes switch from one type of alga to another, and that's exactly what we think we're seeing under climate change.

NARRATOR: And some of these algae are more tolerant to heat.

BAKER: If corals are able to flexibly associate with different types of algae, perhaps they could switch to these more heat tolerant ones and that might help them survive.

NARRATOR: Heat-tolerant algae are less likely to be expelled by the coral, and the coral won't bleach.

If the corals bleached on the raft recover with heat-tolerant algae, they may survive the next ocean heat wave.

And this could be a big step forward for assisted evolution.

BAKER: This is a test-- we're hoping that this is going to be something that proves successful, that is easily scalable, cost effective, and we can roll it out and apply it to the restoration efforts that are going on all over the place.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Today, Andrew's team plants the corals that bleached on the raft out on the reef.

Standard corals act as a control group.

BAKER: We're hoping that the corals that we've bleached on these rafts are going to recover with different symbionts that we hope are more thermally tolerant and that help these corals resist bleaching in the future.

NARRATOR: The corals may now have the ability to survive bleaching, and the next ocean heat wave.

But what about the one after that?

BAKER: If climate change is still ongoing past 2100, then nothing we're doing is going to help solve that.

Ultimately, we have to get carbon emissions under control and try to prevent this runaway warming event.

NARRATOR: And in the midst of this planetary crisis, coral scientists receive devastating news.

At age 56, Ruth Gates, pioneer of assisted evolution, dies.

Yeah, it's difficult to talk about it, but, um... (sighs) I just, it's so hard to believe that she's gone, right?

♪ ♪ HEDOUIN: Ruth was a very inspiring person.

She was always smiling and laughing, and... and so I think, um... yeah, sorry.

She always find a good word and, and the time to be here when you need it.

(laughs) I think that I, I've never laughed so much, um, doing science than I have with Ruth Gates.

It was, we had a great time, and to lose her, it's like a huge piece of the, of the science machine, but also the leadership machine just disappeared.

What she did do was instill so much spirit and motivation to keep going.

HEDOUIN: VAN OPPEN: We wanted to really send out the message that assisted evolution is an important approach to explore, and Ruth, of course, played a very big role in sending that message out across the world and I think we have succeeded.

We've been able to convince the community that this is important.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: When Madeleine van Oppen's team first checked the experimental hybrids, the results were discouraging.

But they didn't give up.

There it is.

(laughs) I knew it was on here, I saw it.

NARRATOR: Tiny young corals are alive on the tiles, signs that these heartier hybrids are surviving life outside the lab, a first for the team.

Well, we still have to take a good look at the data, but we're seeing corals popping up here and there.

Is Grant gonna take it down?

They're gonna take them back out onto the reef, and we'll be keeping those guys out there for another few months until we check up on them again in October.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Back at the sea simulator, researchers share their documentation with Madeleine.

I see some kind of...

Yes, it looks like there's some structure still there, rather than the whole, isn't it?

And it's smooth texture.

QUIGLEY: That is clean.

VAN OPPEN: That one is quite pale, isn't it?

Yeah.

I saw a lot of variability in color.

When we first bred coral recruits in the sea simulator five years ago, everything died between Christmas and New Year.

We had a huge effort, and then the year after we had a little bit longer survival, and so we learned as we went.

These are the baby steps that we have made, but small steps in the right direction.

It gives me hope and I just pray that it's gonna be enough.

NARRATOR: Assisted evolution is now a growing movement around the globe.

Scientists are finding successful solutions that might give corals the chance they need to make it through the coming decades.

Coral Vita is expanding its farming operations beyond the Bahamas, aiming to provide resilient corals to reef rescue operations worldwide.

We can make choices to help our environment, to help our coral reefs, to bring them back to life.

♪ ♪ We are growing corals to be more resilient to the effects that climate change is having on our oceans.

NARRATOR: Super corals tested and planted by the Gates Coral Lab are now being used to restore the protective reef around Oahu.

Andrew Baker's corals bleached and recovered, but did not switch to the heat-tolerant algae.

However, back in the lab, different species have successfully made the swap and are now being planted on reefs off Miami to see if these corals remain resilient in warming ocean waters.

Julia Baum discovered that the corals that survived the mass bleaching on Christmas Island did so because they switched to a heat-tolerant algae naturally.

♪ ♪ Tragically, the reefs around the island of Mo'orea experienced a massive ocean heat wave.

Fifty percent of the corals raised in the nursery perished.

But those that made it proved their resilience and Laetitia Hedouin is optimistic that she will learn from the survivors.

♪ ♪ GATES: We need to know more, so we can harness that knowledge.

I mean, what could be better than that?

Being a part of a solution that will help the world.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S48 Ep4 | 28s | Scientists race to help corals adapt to warming oceans through assisted evolution. (28s)

Scientists Breed a New Generation of "Super Corals"

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S48 Ep4 | 4m 45s | Coral reefs are in crisis as ocean heatwaves are draining them of life. (4m 45s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Science and Nature

Capturing the splendor of the natural world, from the African plains to the Antarctic ice.

Support for PBS provided by:

Additional funding is provided by the NOVA Science Trust with support from Margaret and Will Hearst and Roger Sant. Major funding for NOVA is provided by the David H. Koch...