“The Homeless, Tempest-Tossed” (1942 - )

Episode 3 | 2h 10m 51sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

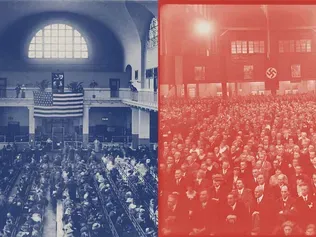

As the Allies liberate German camps, the public sees the sheer scale of the Holocaust.

A group of dedicated government officials fights red tape to finance and support rescue operations. As the Allied soldiers advance, uncovering mass graves and liberating German concentration camps, the public sees for the first time the sheer scale of the Holocaust and begins to reckon with its reverberations.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate funding provided by Bank of America. Major funding provided by David M. Rubenstein; the Park Foundation; the Judy and Peter Blum Kovler Foundation; Gilbert S. Omenn and Martha A....

“The Homeless, Tempest-Tossed” (1942 - )

Episode 3 | 2h 10m 51sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

A group of dedicated government officials fights red tape to finance and support rescue operations. As the Allied soldiers advance, uncovering mass graves and liberating German concentration camps, the public sees for the first time the sheer scale of the Holocaust and begins to reckon with its reverberations.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch The U.S. and the Holocaust

The U.S. and the Holocaust is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipAnnouncer: Funding for "The U.S. And the Holocaust" was provided by David M. Rubenstein, investing in people and institutions that help us understand the past and look to the future; and by these members of the Better Angels Society: Jeannie and Jonathan Lavine; Jan and Rick Cohen; Allan and Shelley Holt; the Koret Foundation; David and Susan Kreisman; Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder; the Fullerton Family Charitable Fund; the Blavatnik Family Foundation; the Crown Family Philanthropies, honoring members of the Crown and Goodman families; and by these additional members.

By the Park Foundation; the Judy and Peter Blum Kovler Foundation, supporting those who remind us about American history and the Holocaust; by Gilbert S. Omenn and Martha A.

Darling; by the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, investing in our common future; By the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and by viewers like you.

Thank you.

♪ Daniel Mendelsohn: There are already people who think that every Jew who died in the Holocaust died at Auschwitz, died in a concentration camp, died in a gas chamber.

No.

There's whole chapters of this story.

Narrator: As hard as Shmiel Jaeger had tried, he had been unable to get himself, his wife Ester, and his 4 daughters out of occupied Poland to America.

German troops had reached his hometown of Bolechow in the summer of 1941.

Within weeks, his daughter Ruchele was murdered.

That was only the beginning.

Mendelsohn: There was another roundup, which was the biggest roundup in my family's town, 2,500 people, and my great-aunt Ester and the youngest girl, Bronia, who was 13 at the time.

They kept them, this huge group of people, in the square outside of the city hall, and there were a lot of atrocities that took place, mostly against children.

There were some Soviet documents that had come to light, including a report, and they listed all the children who had been shot, and actually, Bronia was the first child on the list.

This was in September of 1942.

You know, they were throwing children off the balconies of the city hall, really terrible stuff.

Whoever survived the couple of days of the roundup were shipped to Belzec, and that's where my great-aunt Ester died in the gas chambers.

I was able to find out that Shmiel was hiding with his second daughter, Frydka, and that was because there was a Catholic Polish boy, who was in love with her.

And he was helping to hide her in the home of this local school teacher.

And that for some unknown amount of time, they were being successfully hidden, the father and the daughter, in an underground dugout until someone betrayed them.

And they found them, and they took them, and they shot them both, and then they killed the school teacher, too.

The oldest daughter Lorka joined a partisan group that operated with some Polish partisans in a nearby forest.

She was killed when the whole partisan group was wiped out.

Except for my poor great-aunt Ester, nobody was killed in a camp.

They were killed in all different ways, in all different manners, and I think that already is being erased, the particularity of what happened.

Woman: Here's the tragedy.

Millions of people could not be rescued.

They're in the hands of the Germans.

They're deep into Eastern Europe.

They're in Germany and Austria and France, Belgium, Netherlands.

But there were people who had gotten to Portugal, who had gotten to Spain.

There are people who eventually get to North Africa.

If you had taken more people from those places, maybe more refugees could have come in, maybe more people escaping could have come in.

Are we talking of rescues of hundreds of thousands?

No.

But if it's your family, it doesn't matter if it's one.

♪ Narrator: Just before the United States entered the Second World War, Germany had barred the emigration of Jews from any country it had captured.

For them, occupied Europe had now become a prison to which Adolf Hitler held the key.

Americans were still in no mood to welcome immigrants.

The anxiety about alien subversion that preceded Pearl Harbor only intensified afterward.

FDR declared the West Coast a "military zone" and forced 120,000 persons of Japanese descent who lived there into internment camps.

Most of them were citizens.

The Justice Department also interned thousands of so-called "enemy aliens"-- German and Italian immigrants suspected of fascist sentiments.

"This war can end in two ways," Hitler insisted in early 1942.

"Either the extermination of the Aryan peoples or the disappearance of Jewry from Europe."

Within a few months, the first reports reached the American public that the Nazis had begun systematically murdering every Jewish man, woman, and child on the continent.

Jewish-Americans and their supporters pleaded that somehow, something be done to stop the killing.

But President Roosevelt and his commanders were convinced that only by crushing the Nazis and winning the war as soon as possible could the Allies put an end to it.

Lipstadt: The mantra was, we'll rescue these people by winning the war.

The problem was, and many people knew this, and certainly within government circles, by the time the war would be won, very few of these people would be alive.

[Sizzling] But the dominant idea in the American government is any act of rescue will be a diversion from the war effort.

Both could've been done at the same time.

But clearly nobody wanted these people.

It's not one of the things that will go down in the long annals of good things America did.

It goes in a different book.

♪ Girl: Writing in a diary is a really strange experience for someone like me.

Not only because I've never written anything before, but also because it seems to me that later on neither I nor anyone else will be interested in the musings of a 13-year-old schoolgirl.

Oh, well, it doesn't matter.

I feel like writing, and I have an even greater need to get all kinds of things off my chest.

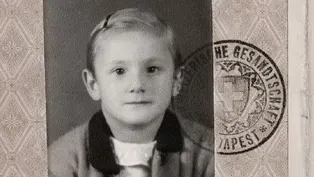

Narrator: In Nazi-occupied Amsterdam, Otto and Edith Frank struggled to provide as normal a life as possible for their family.

June 12, 1942 was their younger daughter Anne's 13th birthday.

Among her gifts was a diary that she was soon filling with profiles of her classmates at the Jewish Lyceum the Germans now required her to attend-- the girls she liked and those she didn't, and the boys she liked and those who seemed to like her.

For the Franks and other Jewish families-- including their neighbors, the Geiringers, refugees from Austria-- life under the Nazis was now anything but normal.

Woman: The first few weeks, nothing had much changed.

And, so, we thought, "Oh, well, perhaps they don't want to do anything in Holland."

The Dutch people were very typical, you know, they said, "You are--you belong to us.

"We are going to protect you.

You don't have to worry about anything."

But they didn't really count on the measures which the Germans were going to take gradually.

And the first year, it became a nuisance.

It interfered with our way of life, but it was not dangerous.

We were not allowed on public transport, for instance.

But we all had bicycles.

But then you had to hand in your bicycle.

And then we had to wear the yellow star, which means that people walk in the street and are recognizable as Jews.

And that started to become really dangerous because people just disappeared.

I didn't want to wear it.

I was stubborn.

I said, "Well, I know I'm a Jew, why do I have to wear a star?"

But everybody had ID cards.

And on Jewish people ID card, it did say you were a Jew, or sometimes there was even a "J" stamped on it.

So, if you would have been stopped without wearing a star, and they asked for your papers, you would have been deported immediately.

Girl as Anne Frank: July 5, 1942.

A few days ago, as we were taking a stroll around our neighborhood square, Father began to talk about going into hiding.

He sounded so serious that I felt scared.

"Don't you worry.

We'll take care of everything.

Just enjoy your carefree life while you can."

That was it.

Oh, may these somber words not come true for as long as possible.

♪ Narrator: The Frank family was in constant danger, and so, they had been slowly moving their belongings to an annex in the warehouse at 263 Prinsengracht in which Otto Frank's business was located.

A few trusted Gentile employees had agreed to help the Franks survive in hiding when the time came.

"We'll leave of our own accord and not wait to be hauled away," Frank said.

But then a registered letter arrived.

Anne's older sister Margot--just 16-- was to be included in the first group of Jewish refugees in Holland to be sent to work in a German labor camp.

The Franks went into hiding the next morning.

Since Jews were now forbidden to ride on streetcars or own bicycles, they were forced to carry their remaining household items through the streets.

[Rain falling, thunder] Girl as Anne Frank: So, there we were, walking in the pouring rain, each of us with a satchel and a shopping bag filled to the brim with the most varied assortments of items.

The people on their way to work at that early hour gave us sympathetic looks; you could tell by their faces they were sorry they couldn't offer us some kind of transport; the conspicuous yellow star spoke for itself.

[Thunder] Narrator: The two floors that Anne would call their "Secret Annex" were accessible only by a single door blocked by a bookcase and cramped even before they were joined by 4 more Jews in need of a hiding place.

The same week the Franks disappeared, their friends the Geiringers did, too-- and for the same reason.

Eva Geiringer's older brother Heinz, like Margot Frank, had been called up for what the Nazis called "labor service."

Geiringer: Heinz was 16, and my father called us together one evening, and he said, "We are not going to send Heinz.

It's too dangerous."

Narrator: Members of the Dutch Resistance had provided them with false papers and places to hide.

But the constant dread of raids by the Gestapo forced the Geiringers to temporarily split up.

Eva was to hide with her mother, Heinz with their father.

Geiringer: I started to cry.

I didn't want to be separated 'cause I was very much attached to my brother and father.

And my father explained, "If we're in two different places, "the chance that two of us will survive is bigger.

So, survive."

So, that was really, you know, the first time that I really realized it's a matter of life and death.

And that's quite scary when you are 13 years old.

I said, "What do you mean?

Will we be killed?"

[Soldiers marching] About once a week, in the night, there was a knock on the door and people had to open up and let them search their homes.

A story had been going around that in another house, the beds were still warm.

They felt the beds.

So, they demolished the whole apartment till they found the people.

And, of course, hosts were taken away as well.

So, of course, when you hear stories like that, people said, "You know, we can't take this tension any longer.

You have to move."

So, we moved about 7 times, my mother and me, to different places.

My mother, she used to be in Austria as a lamb, but suddenly, she became like a tiger, protecting her children.

My father, when we went into hiding, he said, "Don't worry.

It won't be long.

By Christmas, the war will be finished," end of '42.

But, of course, it wasn't.

Girl as Anne Frank: It's the silence that makes me so nervous during the evenings and nights, and I'd give anything to have one of our helpers sleep here.

I'm terrified our hiding place will be discovered and that we'll be shot.

That, of course, is a fairly dismal prospect.

Lipstadt: The "Chicago Tribune" in late June of '42 reports the mass killing of Jews.

Like many other newspapers, the "Tribune" puts it on page 6 or 7 in a tiny, little article.

You either missed it, or if you saw it, you would say the editors don't think this is true.

If they thought this was true, this would be on the front pages.

Narrator: Some papers did put the story on the front page, including the "Pittsburgh Courier," an African American newspaper, which said, "the Nazis could teach even southern whites a few lessons."

3 years after their aborted voyage to Cuba aboard the "St. Louis," Sol Messinger and his parents finally made it to America in June of 1942, aboard the "Serpa Pinto," the same ship that had brought Susie and Joe Hilsenrath 10 months earlier.

Messinger: Our sponsor was a man in Buffalo who had a furniture store.

And he was a relative of a relative whom we knew in Berlin.

He was the one who sponsored us.

It was great to be in the United States, not to be afraid of, you know, policemen.

To be with relatives whom I never knew, but who obviously loved us.

And you could feel or see how people were more or less relaxed, you know, they weren't worried about being picked up by the police and so on.

It just was amazing.

Narrator: As he settled into life in Buffalo, Sol worried about Leon Silber, a friend he had made aboard the "St. Louis" whose family had fled to the same village he had escaped to in the south of France.

Messinger: 6 weeks after we had left, his parents must have heard that something was about to happen.

They went to the teacher and they asked her to hide Leon and she did.

And the next day, the police came and they took the parents away.

Then the second day that he was hidden in the school, he decided he wanted to join his parents.

He left the school and went to the police and said who he was, and he wanted to join his parents.

And he did.

He was killed in Auschwitz.

[Sigh] He was one of one and a half million kids who were killed by the Germans.

Including all my cousins.

Narrator: On July 29, 1942-- a little over 3 weeks after the Frank and Geiringer families went into hiding in Amsterdam-- a well-connected German businessman named Eduard Schulte boarded a train for Zurich in neutral Switzerland.

He had told his staff he would be away on business.

But he had another, secret goal in mind.

From the first, Schulte had seen the Nazis as "a band of criminals;" their war would end only in disaster for Germany, and he had already made this dangerous trip several times to speak with Polish and Swiss agents about likely German troop movements.

Now he had learned from an employee with Nazi contacts that 12 days earlier, Heinrich Himmler had made a formal visit to the concentration camp in occupied Poland now called Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Himmler had spent two days there, had watched the first trainload of 2,000 Jews from Holland arrive, observed the selection of those deemed fit for labor, and looked on impassively as 447 people deemed unfit were immediately put to death, using a new method of which Rudolf Hoess, the commandant, was especially proud.

Instead of relying on carbon monoxide produced by internal combustion engines that frequently broke down, the SS at Auschwitz had begun using commercially available pellets of Zyklon, a powerful vaporizing cyanide-based pesticide that reduced the cost of killing to roughly one U.S. penny per victim.

The same method would be adopted at Majdanek, one of the 6 killing centers in occupied Poland.

Lipstadt: Gas chambers serve one purpose and one purpose only: to murder as many people as you can as efficiently as you can.

Narrator: Himmler was so impressed he promoted Hoess to Lieutenant Colonel and urged him to enlarge the camp as fast as he could.

The "program of extermination will continue," he said, "and will be accelerated every month."

[Train's horn blows] Schulte was determined to get the explosive information to Jewish leaders in Britain and the United States, hoping that they could persuade their governments to do something before it was too late.

In Zurich, Schulte told what he knew to a Jewish banker friend who eventually passed his story on to a 30-year-old representative of the World Jewish Congress, a refugee named Gerhart Riegner.

Woman: Riegner hears third-hand that the Nazis have a plan to gather the Jews together in the East and murder them before the end of the year.

He obsesses over this.

This keeps him up at night.

And, finally, on August 8th, 1942, he decides that he is going to spread this to the world.

He is going to get the Allies to do something about this.

So, he goes to the U.S. Consulate in Geneva and explains what he's learned to the Vice Consul there.

Narrator: Riegner was "a serious and balanced individual," the Vice Consul wrote in his memorandum.

But his boss was dismissive and added a covering note before sending it on to Washington, warning that Riegner's story had all the "earmarks of a war rumor."

That the Nazis persecuted the Jews was undeniable, but the notion that the Nazis were now preparing to kill them all was simply impossible for many in the State Department to believe.

Erbelding: State Department officials decide that this is not good information, and this is crucial, they say, "Even if this were true, there's nothing that we could do about it."

They believe that they are doing all they can to assist the Jews and that any sort of rally or petition or protest asking them to do more would be diverting resources from the war effort.

Many of these people were also racist and antisemitic and nativist.

And, so, you have to wonder whether some of their concern, some of their annoyances have to do with the fact that they're being asked to help Jews.

Narrator: But Riegner had also told his story to a British consular official, who passed it on to a Jewish member of Parliament, who passed it on to Stephen Wise, the best-known rabbi in the United States.

Wise took it to Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles, who asked him to say nothing until he could find out how much truth there was in it.

Wise was nearing 70, exhausted from overwork and in declining health.

He told a friend that these were the unhappiest days of his life.

They have "left me without sleep," he wrote, and "I am almost demented over my people's grief."

Over the next two months, reports from the Vatican, the Red Cross, and from other witnesses supplied by Riegner suggested that the horror he described was real.

Welles summoned Wise back to Washington again and gravely told him that the evidence justified his "worst fears."

Wise called the Associated Press.

There could be no doubt now.

Two million Jews were already dead, he told reporters, which would eventually turn out to have been a gross underestimate-- 4 million had already been killed-- and the Nazis intended to go on killing Jews as long as there were Jews to kill.

♪ The story finally made the front page of the "New York Herald-Tribune," where it appeared with another story, credited to the Polish government-in-exile in London, which described Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto being loaded into freight cars and transported to Treblinka, Belzec, and Sobibor, where, it said, they were being "mass-murdered."

Erbelding: Riegner's message, when it finally reaches the American people in November, 1942, is the first information that the American people really have verified that the Nazis have a plan to murder all of the Jews of Europe.

Narrator: The news was widely circulated by the Associated Press, though its impact was lessened by reports about the fighting in North Africa, where American troops had just landed, and from Stalingrad, where the Soviets had finally broken the German siege.

CBS Radio correspondent Edward R. Murrow, perhaps the country's most respected reporter, was unsparing in his broadcast.

"What is happening is this," he said, "millions of human beings, most of them Jews, "are being gathered up with ruthless efficiency and murdered."

Jewish organizations worldwide declared December 2, 1942 a "Day of Mourning."

On December 8th, Stephen Wise and 3 other Jewish leaders met with the president.

"Unless action is taken immediately, the Jews of Europe are doomed," they told him.

Roosevelt said he was aware of the Nazi "horrors" but had no remedy at hand.

"We are dealing with an insane man," he said.

"Hitler and the group that surrounds him are psychopathic.

That is why we cannot act toward them by normal means."

Roosevelt: The first is freedom of speech... Narrator: Even before the United States entered the war, Roosevelt had made one of his over-arching goals the "freedom of every person "to worship God in his own way, everywhere in the world."

Roosevelt: ...in the world.

Narrator: And he had repeatedly denounced Nazi crimes and promised that those who committed them would be punished once victory was won.

But he had always been careful to maintain that Hitler's victims included all sorts of people, not specifically Jews.

Erbelding: The War Department does not want American soldiers to even know very much about the persecution of Jews because they feel like the soldiers won't fight hard if they think that they are secretly being sent to save the Jews.

And Jewish organizations are obviously very sensitive to this.

They don't want to have Americans perceive this as a war for the Jews.

[Explosion] Narrator: Still, 9 days after Roosevelt met with Rabbi Wise, the United States joined in an Allied declaration issued simultaneously in Washington, London, and Moscow.

The statement condemned "in the strongest possible terms this bestial policy of cold-blooded extermination," and reaffirmed the Allies' "solemn resolution to ensure "that those responsible for these crimes "shall not escape retribution, and to press on with necessary practical measures to this end."

But no specific practical measures were recommended other than victory on the battlefield.

Man on newsreel: Through town after Tunisian town, the 8th army triumphantly marches, pushing the retreating... Man: What does that declaration say?

It says, "We're going to punish the perpetrators.

Full punishment of the perpetrators."

We do rally, as a nation, to defeat fascism.

We just don't rally, as a nation, to rescue the victims of fascism.

Man on newsreel: And now Allied commanders look eagerly across the Mediterranean to the shores of Hitler's fortress Europe.

Man: Three-quarters of the victims of the Holocaust are dead before any American soldier is in continental Europe.

90% of the victims of the Holocaust die in the northeast quadrant of the European continent: Poland, Lithuania, and today, Belarus, Ukraine, but then the Soviet Union.

They are all out of reach of American aircraft in Great Britain.

There is no way American aircraft could have flown to any of those death camps and impeded the killing process while it was at its most intense in 1942 and in January of 1943.

I think the only thing they could have done was to publicize what was happening more and to organize behind the scenes resistance.

But they were always inhibited about this because remember, Nazi propaganda was that Roosevelt and Churchill were the tools of the Jews.

They were fighting the war for the Jews.

And the Nazis used this propaganda to great effect.

And anything the Allies did that seemed to be explicitly defending Jews ran the risk of playing into the hands of that propaganda.

Narrator: Despite the front-page coverage, despite the Allies' declaration, a Gallup poll taken early in January, 1943 showed that fewer than half of its respondents could bring themselves to believe that the Nazis could possibly have killed as many as two million Jews, let alone 4 million.

Woman: Druja, Poland, Tuesday, 4 A.M., June 16, 1942.

My dear ones!

I am writing this letter before my death, but I don't know the exact day that I and all my relatives will be killed, just because we are Jews.

We are all hiding in one dugout.

My hand trembles and it's hard for me to finish writing.

Farewell.

In the name of everybody: Father, Mother, Sima, Sonia, Zusia, Rasia, Yehezkel.

And in the name of Zeldaleh the toddler, who doesn't understand anything yet.

Fanya Barbakow.

Man on newsreel: The Volga, where the great counteroffensive by the Soviet army is commanded by General Zhukov.

He directs the strategy of Russian victories.

On the Stalingrad front, we see the kind of fighting tactics that first stopped the Germans and now is hurling them back, trapping huge numbers of them.

Narrator: In early 1943, the tide of battle turned against the Nazis.

At Stalingrad, the Soviets, armed and supplied with American trucks and tanks and aircraft, had destroyed the entire German 6th Army.

In North Africa, British forces had captured 250,000 German and Italian prisoners-- and saved the lives of hundreds of thousands of Jews who had lived or sought sanctuary there.

Meanwhile, the pace of the Nazi slaughter of Jews slowed, largely because so few survived to be killed.

Those who did survive were needed for slave labor or lived mostly in Romania and Hungary, countries that were allied with but not controlled by the Nazis.

In America, agitation for action against the killing accelerated.

Rabbi Wise and the heads of several other well-known Jewish organizations continued to offer advice to the Roosevelt administration, but that advice had been discussed and either rejected or ignored before.

And they were soon faced with a rival group more militant than theirs.

Its name kept changing but its philosophy remained the same.

Its founder was Peter Bergson, a recent arrival from Palestine and a member of the Irgun, a Zionist paramilitary group, who would dismiss Rabbi Wise and most of his Jewish allies as timorous "Americans of Hebrew descent," not authentic members of "the Hebrew Nation."

Rescue now became Bergson's cause.

With help from the screenwriter Ben Hecht, he produced an avalanche of newspaper advertisements charging the administration with ignoring the plight of Europe's Jews.

[Men chanting Mourner's Kaddish] Narrator: On March 9, 1943, he filled Madison Square Garden twice with an elaborate pageant called "We Will Never Die!"

Told largely from the viewpoint of the dead, it featured 200 rabbis and cantors and an all-star cast that included Edward G. Robinson, John Garfield, and Paul Muni.

And this is not a Jewish problem.

It is a problem that belongs to humanity, and it is a challenge to the soul of man.

Narrator: The show would go on to Boston, Philadelphia, Washington, Chicago, and the Hollywood Bowl.

Its composer, Kurt Weill, himself a refugee from the Nazis, was pleased by the big crowds it drew but felt the pageant didn't achieve much.

"All we have done is make a lot of Jews cry," he said, "which is not a unique accomplishment."

But it did impress the First Lady and scores of congressmen.

[Applause] While the show was still touring, word came that some of the 70,000 Jews still alive in the Warsaw Ghetto had risen up against the Nazis rather than be deported to Treblinka.

They had already buried artwork, diaries, poetry, and final notes in steel milk cans in the ground.

One teenager wrote that he hoped to "alert the world to what happened in the 20th century.

May history attest for us."

The uprising was the largest Jewish rebellion of the war.

It would take the Germans more than a month to crush it, level the ghetto, and send the survivors to their deaths.

Woman: Freda Kirchwey, "The Nation" Magazine.

In this country, you and I and the President and the Congress and the State Department are accessories to the crime and share Hitler's guilt.

If we had behaved like humane and generous people instead of complacent, cowardly ones, the Jews lying today in the earth of Poland and Hitler's other crowded graveyards would be alive and safe.

And other millions yet to die would have found sanctuary.

We had it in our power to rescue this doomed people and we did not lift a hand to do it-- or perhaps it would be fairer to say that we lifted just one cautious hand, encased in a tight-fitting glove of quotas and visas and affidavits and a thick layer of prejudice.

[Telegraph key tapping] Narrator: Gerhart Riegner-- whose report from Switzerland had alerted America to the ongoing Nazi policy of extermination-- sent Washington another desperate message.

Tens of thousands of Jews deported by the Nazis were now trapped in northern Romania without warm clothing.

They had just endured another harsh winter.

With help from the International Red Cross, Riegner thought he could keep them alive.

He also believed he could help Jewish children still hiding in France escape across the Swiss and Spanish borders.

Erbelding: Riegner had many connections with underground organizations and partisan organizations in these different countries.

And so, his idea was if he could get the money, he could funnel that money into France, into Romania, to people who could buy clothing and food, or who could buy fake documents, or pay off border guards to allow children to escape over the border.

Narrator: Riegner's organization, the World Jewish Congress, could supply the money, but Riegner would need a special license from the Treasury Department, which routinely prohibited all "financial or commercial arrangements within enemy territory."

On June 23, 1943, Riegner's request reached the desk of 34-year-old John Pehle, who ran the Foreign Funds Control department at Treasury.

Pehle: The State Department was quite negative.

It worried about the possibility of funds falling in the hands of the Germans.

However, we went back and decided that we could put safeguards in the procedures, so that no foreign exchange would come to the Germans.

Narrator: Pehle granted the license and sent it along to the State Department for transmission to Switzerland, assuming it would reach Riegner quickly.

But the staff of Assistant Secretary of State Breckinridge Long, who had been adamantly opposed to helping Jewish refugees from the beginning, quietly shelved it.

By the beginning of September 1943, when American and British troops landed in Italy and finally gained their first foothold in Europe, John Pehle insisted that the United States government should take an active role in trying to rescue Europe's surviving Jews-- and he would do everything he could to help.

Erbelding: John Pehle was the child of a German immigrant; his father had come when he was a teenager from Germany, and his mother was the child of Swedish immigrants.

He grew up in Omaha.

He went to college there and then ended up at Yale.

But came from a family that did not always have a lot of money and was an immigrant family.

And, so, I think that made him a little more sympathetic to the plight of people who did not come from wealth or privilege.

Pehle also thinks that the United States is a force of good for the world.

And a force of good for mankind.

And that comes through a lot of his decisions.

The United States cannot be isolationist, that we are part of a global community and that we need to treat everyone as a fellow citizen of the world.

Narrator: On July 28, 1943, the ambassador of the Polish government-in-exile had brought a man named Jan Karski to the White House for a meeting with President Roosevelt.

Karski was a Catholic courier for the Polish underground who had survived Gestapo torture, managed to smuggle himself in and out of the Warsaw Ghetto and a transit camp that exported Jews to the killing center at Belzec.

Roosevelt questioned him closely about the situation in Nazi-occupied Poland.

Narrator: Before he left, Karski asked FDR what message he had for the Polish people.

"You will tell them that we will win this war," Roosevelt said.

"You will tell them that the guilty will be punished.

"Justice and freedom will prevail.

"You will tell your nation that they have a friend in this house."

FDR also tells Karski to meet with Felix Frankfurter, who's on the Supreme Court at the time.

Frankfurter is Jewish.

Karski tells Frankfurter what he's seen in Warsaw and other parts of Occupied Poland.

Lipstadt: The Soviets bring a group of reporters to Babi Yar, where there's been one of the early mass killings of Jews.

And they're walked through by two people who the Soviets say are survivors of this massacre.

And they walk them through the fields where these killings have taken place, and there are bits of bones and broken eyeglasses and teeth and all sorts of things that-- that indicate what has happened.

There were American reporters who were present in this tour of Babi Yar, and one of them wrote a report that was so riddled with doubts... so riddled with questions.

If I were a person reading that and I harbored the least bit of skepticism about the veracity of what was going on, I could dismiss this as war propaganda, as atrocity stories.

And atrocity stories are a shorthand for fake news.

I'm sitting at home in Chicago, Des Moines, St. Louis, New York, wherever it might be, and I'm reading those kind of reports, I'm saying, "This can't be true.

This can't be true."

Narrator: In early October 1943, Heinrich Himmler addressed a meeting of his SS commanders.

By then, more than 4,500,000 Jews had been murdered.

[Himmler speaking German] Narrator: Himmler was doing all he could to keep that chapter from being written.

He ordered his men to dismantle and disguise the sites of the killing centers at Sobibor, Belzec, and Treblinka, where more than one and a half million human beings had been killed, and he insisted that prisoners be forced to dig up the dead, burn their corpses, and grind their bones to powder.

Then he had the prisoners who'd done the ghastly work shot so that no one would ever tell what they had seen or done.

Meanwhile, on the Eastern Front, special "Exhumation Squads" were now retreating ahead of the advancing Red Army, seeing to it that the mass graves of the people whom the Einsatzgruppen and their accomplices had murdered back in 1941 and 1942 were emptied as well.

But in Nazi-occupied Poland, two killing centers continued their daily, deadly work-- Majdanek and Auschwitz-Birkenau-- while one that had been closed, Chelmno, took it up again.

Mendelsohn: Interviewing survivors who could give firsthand accounts, you know, people who were young adults when this happened.

You know, you hear things that, you--you think you've heard it all, and you haven't heard it all.

Trust me.

There are--there's no bottom, as one of my survivors said, to the things that people will do to one another.

The structures of what we think of as our civilized lives, they fall apart very easily.

Surprisingly easily.

Woman: I left behind me a few photos of my nearest ones in the hope that somebody would find them while digging and searching in the earth, and that this person would be so kind as to transmit them to one of my relatives or friends in America or Palestine, if there will still be any of them left.

My name is Frieda Niselevitch, born in Vaiguva.

Narrator: Two days after Himmler's secret speech and 3 days before Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement, Peter Bergson arranged for 400 mostly orthodox rabbis to march to the Capitol.

For fear of encouraging antisemitism, FDR's chief speech writer Sam Rosenman and most of the handful of Jewish members of Congress had opposed their coming.

The rabbis sang the "Star-Spangled Banner," recited the Kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead, and met with Vice President Henry A. Wallace.

Man: We pray an appeal to the Lord, blessed be he, that our most gracious President Franklin Delano Roosevelt consider and recognize this momentous hour of history and the responsibility which the Divine Presence has laid upon him, that he may save the remnant of the people of the Book, the people of Israel.

And we pray that the Lord may aid us to gain complete and speedy victory on all fronts against our enemies and that we may be blessed with everlasting peace.

Narrator: The president did not see the rabbis.

But they had an impact nonetheless.

Several senators and congressmen introduced a resolution calling for a new commission tasked with somehow saving "the surviving Jewish people of Europe."

Assistant Secretary of State Breckinridge Long testified against it for 4 hours behind closed doors.

There was no need for such a commission, he said, since the State Department had welcomed 580,000 "refugees" to America since 1933.

It was not true.

The real refugee number was one-third of that.

Lipstadt: Breckinridge Long, in his testimony, clearly misrepresents, some would say lies, but the best you can say is it's a total misrepresentation of America's record.

He was crazed about preventing any refugees from coming here.

Narrator: The resolution stalled in the House.

And when Long's testimony became public a couple of weeks later, Brooklyn Congressman Emanuel Celler called for his immediate resignation.

Man as Celler: The tempest-tossed get little comfort from men like Breckinridge Long.

If men of his temperament and philosophy continue in control of immigration administration, we may as well take down that plaque from the Statue of Liberty and black out the "lamp beside the golden door."

Narrator: At the end of 1943, Gerhart Riegner was still waiting for the all-important license he needed to help Jews in Romania and France, which John Pehle had approved 5 months earlier.

Breckinridge Long and his staff continued to stall, raising every possible potential barrier, even though the president himself was on record favoring it.

Pehle: The people who were handling visa matters, and the policy of the State Department, seemed to be such that instead of facilitating the entry of refugees, obstructions were thrown in the way.

It's as simple as that.

Narrator: Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, Jr. was the president's close friend and upstate neighbor, as well as the only Jewish member of his cabinet.

All through the Hitler years, he had been careful never to seem to be seeking special treatment for his fellow Jews.

But this was too much.

He confronted Long and the Secretary of State Cordell Hull.

The license was finally issued, but in the course of investigating the reason for the lengthy delay, Morgenthau's staff discovered that the State Department had deliberately suppressed Riegner's reports from Switzerland about the extermination of the Jews.

Pehle: People in the State Department were saying, "Don't send any more messages over about what's happening to the Jews. "

Erbelding: The State Department has been deliberately obstructionist, they have been delaying relief money that could go to Jews in occupied Europe, and lying about it, so that people would stop rallying, they'd stop protesting, and they'd stop asking the government to do more.

Narrator: Morgenthau's outraged aides wrote an internal report setting forth the evidence of the State Department's deceit.

Man: It appears that certain responsible officials of this government were so fearful that this government might act to save the Jews of Europe if the gruesome facts relating to Hitler's plans to exterminate them became known, that they attempted to suppress the facts.

We leave it for your judgment whether this action made such officials the accomplices of Hitler in this program and whether or not these officials are not war criminals in every sense of the term.

Narrator: Treasury staff titled the document "Report to the Secretary on the Acquiescence of this Government in the Murder of the Jews"... but Morgenthau, who understood his boss better than most, toned down the accusatory rhetoric and renamed it simply "Personal Report to the President."

Morgenthau's own father, who had been the ambassador to what was then the Ottoman Empire between 1915 and 1916, had tried unsuccessfully to persuade President Woodrow Wilson to intervene on behalf of hundreds of thousands of Armenian civilians who were being systematically massacred by Ottoman troops.

He had called it "race murder."

Erbelding: Henry, Jr. went to Turkey, went to Constantinople, now Istanbul, to see his father as all of these events were unfolding.

He points to that directly to Roosevelt.

He says, "You remember what my father saw.

"You remember what I saw in Armenia.

We can't let this happen again."

To be the Secretary of the Treasury and to be in a position to actually point his friend to the past and to say, "We have the chance to do it better this time."

Narrator: After a meeting with Morgenthau and Pehle, Roosevelt issued an executive order on January 22nd, 1944, establishing the War Refugee Board-- the only government agency created by any of the Allies specifically to do what it could for the Jews still under Nazi threat.

Treasury was in charge and John Pehle was made director, determined to perform what he called "a simple life-saving job."

Pehle: The most important thing about the War Refugee Board was that it dramatically changed the policy of the United States overnight.

Erbelding: 5 million Jews have already been killed in Europe.

But there are millions who are still there, who are in hiding, who are in concentration camps, who are still, they think, in relative safety, who could get out, could be rescued, could cross borders, could be kept alive long enough to be liberated.

Narrator: The work undertaken by the Board's representatives in Europe was improvisational and clandestine.

Official U.S. policy forbade paying bribes.

Pehle's men paid little attention.

Erbelding: The first thing that the War Refugee Board does once it's created is to streamline the license process, meaning humanitarian aid organizations can send money into Europe much easier.

By the end of the war, the War Refugee Board has approved about $11 million in humanitarian aid to go into Nazi Europe.

That money was used to buy guns for the underground; it was used to pay off border guards.

The plight of Jews varied, depending on where you were in Europe.

If you were in France, you might be able to escape to the border in Spain or Switzerland.

And, so, the United States puts pressure on border guards in Spain and Switzerland.

If you were in Romania or Bulgaria, you might be able to board a ship and make it to Turkey, and then by train to Palestine.

So, the War Refugee Board works with governments to make that process easier.

And if you're in Poland, you may need food packages or documents that would allow you to hide, so, the War Refugee Board tries to help with that.

And, so, they had a whole host of different plans that had real impact on the lives of the people who managed to survive.

Narrator: Much of the Board's most effective work was focused on Hungary, which in early 1944 was still home to some 800,000 Jews, the largest remaining population in Europe.

Its Regent, Admiral Miklos Horthy, had been a Nazi ally since 1941, when his troops joined the German invasion of the Soviet Union.

[Gunfire, explosions] But most of the Hungarian army had been destroyed at Stalingrad.

Because Nazi defeat now seemed inevitable, Horthy began secretly exploring whether a separate peace with the Allies might be possible.

When Hitler got word of it, he sent in troops to occupy the country and insisted that Horthy cooperate in ridding Hungary of its Jewish population.

Between May and July 1944, some 440,000 Hungarian Jews would be rounded up and deported.

338,000 of them were killed immediately at Auschwitz-- so many that the 4 crematoria were not enough and fire pits had to be dug and constantly tended to dispose of all the corpses.

Members of the Polish underground managed to smuggle a camera into Auschwitz so that 5 courageous inmates could document what was happening to the Hungarians and other prisoners.

[Camera's shutter clicks] While 4 men kept watch, a fifth snapped 4 pictures from the hip, not daring to take the time to focus.

[Camera's shutter clicks] The film was smuggled out of the camp inside a tube of toothpaste.

[Camera's shutter clicks] They remain the only photographs of the killing process at Auschwitz.

[Camera's shutter clicks] Meanwhile, in Hungary, the War Refugee Board helped orchestrate a massive international series of threats and condemnations aimed at persuading Horthy to stop cooperating in the killing.

Then, on July 2nd, U.S. bombers hit oil refineries on the outskirts of Budapest and dropped leaflets on the city promising punishment for perpetrators.

5 days later, Horthy called a halt to the deportations.

Hungary's provinces had been emptied of Jews, but some 230,000 still survived in Budapest itself, subject to persecution, fearful that the transports might resume at any time.

To protect them--and to glean firsthand accounts of what was happening in Hungary-- the War Refugee Board called upon neutral nations, including Switzerland, Portugal, and Sweden, to expand their diplomatic presence in the country.

Their diplomats in Budapest began issuing so-called "protective documents" to desperate Jews-- sheets of paper emblazoned with coats of arms and peppered with official-looking stamps, intended to persuade Hungarian police and German officials that the bearer was under international protection.

Man: It's no coincidence that the War Refugee Board ends up making a difference in Hungary because that's a-- that's a country which is a sovereign state, which still has diplomats, where a diplomat can be sent in, with briefcases full of money, and issue documents and make a difference.

Narrator: On July 9th, a 31-year-old Swedish businessman named Raoul Wallenberg arrived in Budapest to accelerate that process.

Appointed a Swedish attache but recruited and partially financed by the War Refugee Board, he saw his mission as carrying out an "American program."

He established hospitals, nurseries, and a soup kitchen, issued thousands of protective papers, and rented 32 "safe-houses" for those who carried them.

Diplomats from other neutral countries also participated in rescue operations, most notably the Swiss vice-consul Carl Lutz.

Soon, some 37,000 Jews were living under Swedish and Swiss protection in what was called the "international ghetto."

When Hitler replaced the Horthy government with more ardent fascists, who resumed the deportation of Jews, Wallenberg intervened as often as he could to win the release of those with protective or forged papers.

Of the nearly 150,000 Jews in Budapest who would survive the war, some 120,000 are thought to have owed their lives to Raoul Wallenberg and his fellow diplomats from neutral nations.

It is impossible to tally how many tens of thousands of lives the War Refugee Board saved, directly or indirectly.

Erbelding: These were Americans who were really trying to do good.

And we have forgotten them, in part, because we have this longer narrative and trajectory in our memory of the United States not doing enough, being indifferent, being deceitful, not trying to save people.

There is a group of people in the U.S. government who were trying and who saved tens of thousands of lives by the end of World War II.

That is not insignificant.

[Static] Man on radio: This is the BBC Home service.

Communique number one, issued by supreme headquarters allied expeditionary force.

[Static] Dwight D. Eisenhower: People of Western Europe, a landing was made this morning on the coast of France by troops of the allied expeditionary force.

This landing is part of the concerted United Nations plan for the liberation of Europe... made in conjunction with our great Russian allies.

I have this message for all of you.

[Gunfire] Although the initial assault may not have been made in your own country, the hour of your liberation is approaching.

Man: This concludes the broadcast from supreme headquarters allied...

Girl as Anne Frank: Tuesday, 6 June, 1944.

"This is D-Day," the BBC announced at 12.

"This is the day."

The invasion has begun!

The best part about the invasion is that I have the feeling that friends are on their way.

Those awful Germans have oppressed and threatened us for so long that the thought of friends and salvation means everything to us!

Narrator: Within 24 hours, the Allies had torn a 45-mile gap in Hitler's Atlantic Wall in Normandy.

More than 150,000 men were already ashore in France, and more men and more equipment and supplies were coming ashore every day.

Stern: And then I was suddenly on French soil.

And a voice from a few hundred yards away, one of my buddies, was shouting, "Stern, get the hell over here.

"We've got too many prisoners and we've got to have you."

Narrator: Guy Stern, now a staff sergeant, came ashore on D-Day plus three.

He was part of a special Army intelligence unit that included many Jewish refugees trained to interrogate enemy soldiers as they surrendered.

Stern: My own personal incentive was if I help shorten the war, let's say by an hour, I have a chance.

If my family somehow escaped the same perils as the others, I would be there still in the nick of time to be their savior.

[Rumbling] Narrator: Over the next 3 months, nearly 50,000 Americans would die in the struggle to liberate Western Europe from the Nazis.

[Explosion] As the Allies fought their way inland, Guy Stern and his comrades would cross-examine hundreds of prisoners, gleaning vital information about troop movements and the location of industrial targets.

And they interrogated a Nazi doctor who proudly boasted that he had overseen the killing of thousands of disabled people Hitler had called "unworthy of life."

Meanwhile, the Red Army, which had suffered millions of casualties, was moving westward into Poland.

[Film reel clicking] As it did, it came upon the death camp at Majdanek, where 18,000 Jews had been murdered in a single day in 1943 in an operation the SS called the "Harvest Festival."

The spectacle of hundreds of starving prisoners of war the Germans had abandoned and the stark evidence of the industrial scope of the Nazi slaughter offered Allied correspondents their first look at a German killing center.

Lipstadt: When Majdanek is liberated, American reporters are there, and they send back reports that are devoid of the doubts that were shown when Babi Yar was liberated a few months earlier.

Americans are beginning to get the picture.

Man: I am now prepared to believe any story of German atrocities, no matter how savage, cruel, and depraved.

William H. Lawrence.

Man on newsreel: 20,000 wounded arriving in New York.

And there it is, the good old USA... Narrator: On August 3, 1944, a 29-ship Navy convoy steamed into New York Harbor.

The troop transport "Henry Gibbins" carried wounded soldiers and sailors, but also aboard were 982 civilian refugees belonging to 18 countries, chosen from among thousands of refugees who had managed to reach Allied territory in Italy.

Their destination was Fort Ontario, New York.

Ray Morgan: Under the supervision of the War Relocation Authority, this train is bearing 982 refugees from Hitler's total war.

Admitted to the United States... Narrator: The rationale for their arrival had originated with John Pehle and the War Refugee Board, who proposed a trial program going outside the quota system to bring refugees to camps in the U.S. until the war was over and they could return home.

The White House commissioned a Gallup Poll that showed 70% of Americans now supported the idea of sheltering refugees from Europe temporarily.

918 of the refugees were Jewish.

The rest belonged to various Christian denominations, included so that the public would not think this was exclusively "a Jewish refugee project."

To some refugees, it seemed all-too-reminiscent of the concentration camps they had escaped-- run-down barracks walled-in by chain-link fences topped with barbed wire.

But most felt relief and gratitude.

"This is paradise," one said.

Another exulted that she now had "a villa on Lake Ontario."

"This is the first time I have been happy in 11 years," said a third.

A few local citizens resented the foreigners, but most townspeople proved friendly.

Soon, they were passing food and milk, dolls, and even bicycles over the barbed wire.

Refugee children were enrolled in public school, the Boy Scouts, and the Brownies.

Their parents were given day-passes, but forbidden to work outside the compound so that they would not compete for American jobs.

The First Lady and Henry Morgenthau's wife visited the refugees.

Mrs. Roosevelt was moved by the "character" which had brought them through so much, she said, and privately thought it "perfectly silly" that they were required to return home one day.

And after the war, she would be instrumental in seeing to it that all who wished to remain in the United States were allowed to do so.

But for the rest of the war, no more refugees outside the limited quotas would be offered even temporary shelter in the United States.

Girl as Anne Frank: I still believe, in spite of everything, that people are truly good at heart.

It is utterly impossible for me to build my life on a foundation of chaos, suffering, and death.

I see the world being slowly transformed into a wilderness.

I hear the approaching thunder that one day will destroy us, too.

I feel the suffering of millions.

And yet, when I look up at the sky, I somehow feel that everything will change for the better, that this cruelty too will end, that peace and tranquility will return once more.

In the meantime, I must hold on to my ideals.

Perhaps the day will come when I'll be able to realize them.

Narrator: The Frank family had managed to evade the Germans in Amsterdam for two years and one month.

But on August 4, 1944, a Nazi officer and several Dutch policemen arrested them and the other residents of their secret annex.

They were sent to Westerbork, a holding camp in the Netherlands for Jews awaiting deportation to the East.

There, they were housed in Barrack 67 in the punishment block, reserved for those who had been caught hiding.

Their heads shaved, with too little to eat, they were put to work turning parts of downed Allied aircraft into useful scrap.

Trains had been leaving the camp for occupied Poland every Tuesday.

The Frank family was forced to board theirs on September 3, 1944, along with 1,015 other people.

Theirs would be the last train from Westerbork.

It would take them 3 days and two nights to reach their destination-- Auschwitz.

The Geiringer family had been rounded up earlier by the Gestapo and deported to Auschwitz as well.

Geiringer: The Nazis never told you anything.

So we had no idea where we were going, what was going to happen to us.

And there were some work camps, but we were lucky we were sent to Auschwitz and not to Treblinka, for instance, where the whole transport, no selection, whole transport went into the gas chambers.

So then you had no chance, whatsoever.

At least, we had a chance.

But the first terrible thing was at arrival, men and women, to different sides.

That was the first command.

And you can imagine what scene that was because people thought, and it did happen, of course, many times, that people never, ever saw each other.

So my mother and father embraced and Heinz and my mother and my father and me.

And my father then did something which I remember very clearly.

He took me by the hands and he said, "Evertje"-- that's a Dutch name for Eve, "Evertje, God will protect you."

And that was amaz--I was amazed at that because he was not really religious.

But, at that moment, he realized... nobody else could do it.

But, if there is a God, he should--will look after me.

Yeah.

And, then, the men walked away.

My mother gave me this hat and coat.

And I didn't want to wear it.

It was very hot.

But she said, "Well, perhaps, it might come in useful later."

And, then, the camp doctor appeared, youngish man, very smart with a little stick like a conductor.

And he looked you over, just a fraction of a second, and he conducted you either right or left.

And because this rim of this hat was big, he didn't see how young I was.

So that was the first miracle.

They told us with laughing that the family you have been separated were taken to a shower, but it wasn't, of course, a shower, it was gas.

And within 15 minutes, they were all killed.

And then, everything was taken away.

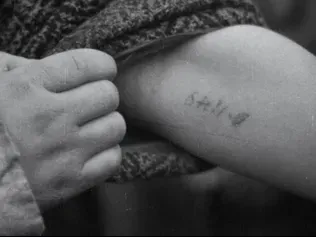

Then we were registered.

We were all tattooed.

We were told, "You are not a human being.

"You're just like cattle, who gets--get a number.

"If ever we need you, you're going to be called out by your number."

All of our hair was shaved and naked, and then they told us, "Now it's your turn to go in the shower."

Of course, we didn't want to go, but we were pushed into it.

But it was an actual shower.

We were herded into our barracks, which were low, wooden barracks with--and a sort of a chimney in the middle.

And both sides were bunks, 3 high, like cages.

They told us, "That's where you will spend your night, as long as you are alive."

Narrator: In late October, John Pehle received another horrific report from Switzerland.

It contained firsthand testimony from 3 men who had managed to escape from Auschwitz and provided meticulous details of what they had seen there.

Pehle: The Board seized upon this.

Now we had the eyewitness accounts.

♪ Narrator: Pehle said the report "ought to be required reading for the people of the United States."

Erbelding: The release of the Auschwitz Report is headline news throughout the country.

These news reports explaining to the American people what Auschwitz was and what happened there are followed up by op-eds, by columns about Auschwitz and what America has to do in the wake of all of this information.

Lipstadt: And the fact that it's released by the War Refugee Board.

It's not being released by a Jewish organization.

It's not being released-- Rabbi Stephen Wise says it's coming from a governmental source.

It's much harder to dismiss it.

Greene: There's a poll in late 1944, and the question is asked, "Do you believe the Germans are murdering Jews in concentration camps?"

It runs in the "Washington Post."

76% of Americans by that time believe that it's happening, but then they're asked the numbers, "How many Jews do you think have been killed?"

And Americans cannot grasp the scale and the scope of the crime.

It's only one in 5 Americans believe that it's more than a million Jews who have been murdered.

And, by that point, it's more than 5 million.

Geiringer: Within a day, we were already covered in lice.

Bedbugs were kind of like a nail, thumbnail, little animals with--had legs, and they'd cling to your skin and suck your blood.

And it became very infected and itchy and so on.

Once a week, we had a shower that was a delousing, and you never knew was it gassing or a shower.

Nobody had any periods.

It was a blessing 'cause we couldn't cope with that.

I mean, the toilets were just cement sinks with holes in the middle.

And you had to sit where, usually, everything was already filthy from diarrhea.

And if you didn't sit, because you tried to not sit on it, you were beaten up to sit in that.

And the other thing was when you went to work outside, march, if you wanted to escape, there was no chance to escape.

The dogs were there, dogs tore you apart, killed you, we saw that.

You were caught when you went out of your line, and then you were taken back to the camp and there--there was a camp center, a square sort of.

Each bit of the camp had that.

And then they erected gallows, and we had to watch, we were all called, and we had to watch this be-- person being hanged there, slowly, you know, with the tongue coming out of them.

Of course, you had to watch, but, of course, we closed our eyes.

But even they'd check that you look.

You know, there were people who just couldn't tolerate it any longer and they wanted to die.

And you couldn't even commit suicide, you know?

You had no string or--or you had no pills or anything.

You know?

So the only thing was to throw yourself against electrified barbed-wire, and it was strong currents.

And then, we heard terrible screams, and you saw people burning on this wire because you're stuck on it, and you went up in flames.

Narrator: Even before the report about Auschwitz was published, Jewish organizations, hoping to save the thousands of Hungarians still being sent there, had called for the Allies to bomb the railroad tracks leading to the camp, and then for the bombing of Auschwitz itself.

Their appeal eventually reached the War Refugee Board.

Pehle: As a non-military people, we were hesitant to press the War Department to send bombers, which would otherwise be used to bomb German cities, for this purpose.

We were concerned about the reaction of the American people... [Gunshot] if troops died in this sort of expedition.

We went into this matter further and with much soul searching, because we were very concerned that going in we would kill a number of Jews.

Narrator: But after reading The Auschwitz Report, Pehle changed his mind.

Pehle: The time came where we felt that the situation was so desperate that we should ask the War Department to do it.

And we did.

And not only should the rail lines be bombed, but the crematoria should be bombed, too.

We became capable of doing it because Allied troops had advanced far enough up the Italian boot that we had acquired an old Italian airbase at a place called Foggia.

And if you flew northeast from Foggia, you could get a plane to Auschwitz and back on a single tank of gas.

Narrator: But the Allies had already learned that railroad tracks could easily be repaired overnight, that rail traffic could only be halted permanently by waves of airplanes hitting them day after day.

In the repeated raids that would have been required to ensure the destruction of the gas chambers and crematoria, hundreds, if not thousands, of the people imprisoned in the camps would likely have been killed or wounded.

And Allied aircraft were otherwise engaged... first in blasting a way forward for the Allied troops through the Normandy hedgerows, then destroying bridges to trap the retreating Germans and taking out the fuel and armament plants that powered the Nazi war machine, all military objectives aimed at bringing about the quickest possible end to the war.

Man: 3 planes, 9 o'clock, coming around.

Keep your eye on them, boys.

Narrator: More than 52,000 American airmen were killed trying to achieve those Allied objectives.

[Gunfire] Man 2: We have an engine on fire.

[Gunfire] Man: Pull her up!

Hayes: If it had become known in the American public in 1944 that planes and pilots and crews had been lost in bombing what was a non-military target, that would have not been without repercussions.

Narrator: The U.S. Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy dismissed the idea of bombing Auschwitz as "impracticable."

The mission, he wrote, "would have had a most uncertain, if not dangerous effect."

Greene: The United States is bombing German munitions areas 4, 5 miles from Auschwitz.

Would they have hit their target?

That's--that--that's another question.

Narrator: So-called "precision bombing" during World War II was spectacularly imprecise.

One study showed that just one bomber out of 5 hit within 5 miles of its intended target.

When Allied bombs intended for the I.G.

Farben fuel and rubber plant several miles away accidentally hit inside Auschwitz, killing dozens, one man, a Dutch physician, testified to the "fear and agony" he and his fellow prisoners had felt.

But others, including the future writer Elie Wiesel, later remembered having been willing to be bombed if it meant an end to the killing.

No contemporaneous evidence exists that FDR himself was ever consulted about bombing Auschwitz, but many years later, John McCloy claimed he had spoken with him, and that the president had rejected the idea out of hand.

"They'll only move it down the road a little way," he said he remembered the president saying.

"I won't have anything to do with it.

"We'll be accused of participating in this horrible business."

Lipstadt: I think they should have, not because it would have rescued a major portion of the 6 million, but as a statement, as a message to the Germans, "We know what you are doing.

"We cannot abide what you are doing.

This is our response to what you are doing."

Yes, it could have done that.

Erbelding: I don't think there's a right answer in whether we should have bombed Auschwitz.

I don't think there's a right answer because I don't think there's a way in which we look back and think that we did the right thing.

I think it is one of those tragic questions in which we are either the people who knew that there was a concentration camp there and did not try to bomb it, or we knew there was a concentration camp there and we bombed it.

We bombed prisoners, we bombed people who might have otherwise survived.

And that is the tragic question of this is, no matter what we did, I think we'd look back and--and wonder what happened-- what would have happened had we done the other thing.

Narrator: In mid-January 1945, the prisoners at Birkenau and Auschwitz had begun to hear distant Russian artillery coming closer, and then the sound of German vehicles beginning to rumble away.

The last gassing of 1,700 Jews had taken place at the end of October 1944.

Afterwards, the SS blew up and bulldozed all but one of the gas chambers and crematoria, burned records, and began marching prisoners on foot through the snow back toward Germany.

Between 700,000 and 800,000 survivors from Auschwitz and scores of other abandoned camps were now staggering along the roads or packed into open coal cars, retreating ahead of the Soviets.

Around a quarter of a million would die between the first of the year and the war's end, exhausted or frozen, shot or burned alive by their German guards.

Some 7,000 people remained at Auschwitz, too frail to leave the camp.

When the marches started, Eva Geiringer's mother Fritzi was too weak and ill to move.

Eva crawled into her mother's bunk, and they huddled together against the cold.

Geiringer: Most people couldn't even leave their bunks anymore.

They said, "Everybody out.

We are going to march.

"If you are staying, we are going to lock up the barracks and burn everything down."

And my mother was so weak, and it was so cold.

And I said, "Let's just stay."

We fell asleep.

And they must have called out again, "Out," and we didn't hear that.

When we woke up, there was no shouting, no dogs.

It was very, very empty.

And then I see out of the gate a huge creature with icicles hanging down his face and his--and all fur, and from the distance, we thought it was a bear.

But it wasn't.

It was a Russian scout to investigate if the army should fight or if they can just advance.

And he came in and looked at us, and he said, well, he has to go back to report.

And so, I decided I would go to the men's camp to try to find my father and brother.

It was very, very cold.

And the fighting was going on around us.

And I heard bullets going over.

It took me about 6 hours.

[Gunshots] And I didn't really know where to go.

But I found it, eventually.

And I found two people who I had known in Amsterdam.

And one was--looked very familiar, and I said, "I think--I think you--you look--I know you," but he looked very gaunt and ashen.

And it was Otto Frank.

Narrator: Barely able to walk after a fearful beating, Otto Frank, too, had been left behind.

Nearly 6 feet tall, he now weighed just 114 pounds.

Geiringer: And the first question, of course, "Have you seen my girls and my wife?"

And I hadn't seen them, because, you know, they're all the different camps.

But he had seen my father and brother.

So, at that time, I thought, "Oh, good.

Well, I'm sure they'll be alive."

♪ ♪ Narrator: Otto Frank would later write his mother in Switzerland to tell her that he had survived.

Man as Frank: Where Edith and the children are, I do not know.

We have been apart since September, 1944.

I merely heard that they had been transported to Germany.

One has to be hopeful to see them back well and healthy.

Narrator: Frank would eventually learn that he had been misinformed.

His wife had not been sent to Germany.

Instead, she had died at Birkenau, just 3 weeks before the Soviet Army came.

To the end, Edith had kept bits of bread beneath her blanket in case she somehow saw her husband and daughters again.

The Soviets transported Otto Frank and Eva Geiringer and her mother by truck and train to Odessa on the Black Sea.

Eva's brother and father were still missing.

The refugees were lodged in a crumbling palace overlooking the beach and told they would have to stay there until the war ended.

"Everybody is impatient, in spite of daily chocolate and cigarettes," Frank wrote in his diary.

They just wanted to go home.

As Allied armies converged on Germany in the spring of 1945, one by one, they came upon the concentration camps that the Reich had tried to keep secret.

The Soviets, driving westward, had already over-run all 6 of the German killing centers where more than 3 million human beings had been murdered-- Auschwitz, Belzec, Majdanek, Sobibor, Treblinka, Chelmno.

British and Canadian troops were about to capture Neuengamme and Bergen-Belsen in northern Germany.

And in early April, soldiers of the U.S. 4th Armored Division searching for a supposed German headquarters, came upon Ohrdruf, one of at least 130 satellite camps surrounding a far larger one--Buchenwald.

These camps inside Germany itself were not officially killing centers like those in occupied Poland, but they were places to which people were sent to die after untold hours of forced labor, starvation, exhaustion, disease, and hopelessness.

Among the first Americans to enter Buchenwald was an Army private, Benjamin Ferencz, who had been assigned to a new unit tasked with investigating German war crimes.

Ferencz: I jumped into my Jeep.

I raced there.

I found the American tank officer who had liberated the camp, had gotten there first.

I said, "I'm out here on orders "carrying out a policy of the United States Government.

"I need 10 men, immediately, to surround the schreibstube, the office where the records are kept."

The crematoria were going; smoke in the air, the smell of burning bodies in the air.

In front of the crematoria, stacks of bones.

They were human beings.

And they were so thin that they just looked like bones.

And they were stacked up in front of the crematoria, waiting to be burned.

That was my introduction to Hitler's plan in action.

I thought to myself, "It can't be real."

And it was unbelievable.

But, it was true, and I knew, of course, it was true.

Narrator: Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight Eisenhower flew in to see for himself.

When a young GI nervously laughed, Eisenhower glared at him, "Still having trouble hating them?"

he asked.

"We are told that the American soldier does not know what he is fighting for," he said.

"Now at least he will know what he is fighting against."

Lipstadt: When Eisenhower sees this, he orders that a congressional delegation be brought there, and that American editors be brought there.

And they are shocked.

And they describe in great detail what they see.

I think it speaks to the lingering doubts that this could be real.

And it also speaks to an inability to put your head around this.

And I don't say that critically.

I say that this is something that beggars the imagination.

This was a murder that was beyond belief.

And it takes that personal confrontation with the evidence, with the remnants, for them to grasp that.

Narrator: To make sure Americans understood the depths of Nazi depravity and to make sure future generations could never deny what had happened, Eisenhower insisted that military personnel in the area come and see for themselves what the Nazis had done.

Stern: We were actually stationed in Weimar, and we had heard of the Buchenwald Camp.

I lagged behind Sergeant Hadley, who was probably one of the toughest MP soldier I had ever encountered... and people told me their stories.

But it was a skeleton you were talking to.

I looked at them, and I started-- I was a hardened soldier by then, but I couldn't help myself.

So, I was crying.

I looked around and Sergeant Hadley, from a Protestant family in Ohio, he was bawling like a kid, as I was.

You couldn't take it.

But they could.

The perpetrators who could do such a thing, and the victims who had to endure it.

Narrator: American troops would liberate Nordhausen, Flossenberg, Mauthausen, and Dachau, the very first of Hitler's concentration camps.

A GI named Joseph A. Wyant used his off-duty time to visit there, and then wrote home to his father.

Man as Wyant: This particular crime has been uncovered, Pop, but a worse crime seems to me to be the spreading of the thought that leads to this type of thing.

It has happened in mass proportions here in Germany, but who knows how far the ideas have spread or where else it may break out?

I tell you, Pop, even more important than the punishment of the criminals here is the stamping out of their philosophy.

As I wrote you once before, this is not a war between nations, but humanity's struggle for the right to exist.

If you see fit, I wish you would show any of your friends this letter.

Your devoted son, Joe.

[Man chanting "Ki Mitzion" in Hebrew] [All singing in Hebrew] Eichhorn: Today, I come to you in a dual capacity-- as a soldier in the American army and as a representative of the Jewish community of America.

As an American soldier, I say to you that we are proud, very proud to be here, to know that we have had a share in the destruction of the most cruel tyranny of all time.

As an American soldier, I say to you that we are very, very proud to be with you as comrades in arms, to greet you, and to salute you who have been the bravest of the brave.

Narrator: On April 12th, the same day that Eisenhower had toured Ohrdruf, President Roosevelt had died at Warm Springs, Georgia with victory in the war, for which he'd tried to prepare his countrymen, still weeks away.

On May 8, 1945, the Germans finally surrendered.

Hitler had killed himself in his Berlin bunker.

Guy Stern was still in Germany.

Before going back to America, he returned to his hometown to try to find out what happened to his family.

Stern: I went to Hildesheim.

I first was overwhelmed by the ruins of many of the things that I had looked at with my mother.

This history was in rubbles.