“Yearning to Breathe Free” (1938-1942)

Episode 2 | 2h 17m 35sVideo has Audio Description

As war begins, some Americans work tirelessly to help refugees; others remain indifferent.

As World War II begins, Americans are united in their disapproval of Nazi brutality but divided on whether to act. Some individuals and organizations work tirelessly to help refugees escape. Meanwhile, Charles Lindbergh and isolationists battle with Roosevelt to try to keep America out of the war. Germany invades the Soviet Union and secretly begins the mass murder of European Jews.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate funding provided by Bank of America. Major funding provided by David M. Rubenstein; the Park Foundation; the Judy and Peter Blum Kovler Foundation; Gilbert S. Omenn and Martha A....

“Yearning to Breathe Free” (1938-1942)

Episode 2 | 2h 17m 35sVideo has Audio Description

As World War II begins, Americans are united in their disapproval of Nazi brutality but divided on whether to act. Some individuals and organizations work tirelessly to help refugees escape. Meanwhile, Charles Lindbergh and isolationists battle with Roosevelt to try to keep America out of the war. Germany invades the Soviet Union and secretly begins the mass murder of European Jews.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch The U.S. and the Holocaust

The U.S. and the Holocaust is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipAnnouncer: Funding for "The U.S. And the Holocaust" was provided by David M. Rubenstein, investing in people and institutions that help us understand the past and look to the future; and by these members of the Better Angels Society: Jeannie and Jonathan Lavine; Jan and Rick Cohen; Allan and Shelley Holt; the Koret Foundation; David and Susan Kreisman; Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder; the Fullerton Family Charitable Fund; the Blavatnik Family Foundation; the Crown Family Philanthropies, honoring members of the Crown and Goodman families; and by these additional members.

By the Park Foundation; the Judy and Peter Blum Kovler Foundation, supporting those who remind us about American history and the Holocaust; by Gilbert S. Omenn and Martha A.

Darling; by the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, investing in our common future; By the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and by viewers like you.

Thank you.

[Birds calling] [Horn honks] [Laughing] Daniel Mendelsohn: When I was a small child, 5, 6, 7, 8, we would visit my grandpa and his wife down in Miami Beach.

My grandfather was one of 7 siblings.

5 immigrated to the States in the early twenties.

They would gather together their old pals, and some of them would get very emotional when they saw me because they said I bore an uncanny resemblance to my great uncle Shmiel Jaeger.

I felt haunted by this guy because people looked at me and they thought of him.

We had pictures of Shmiel and Ester, his wife, and these girls as they grew up in a provincial town in Eastern Poland because all through the 1920s they were sending pictures as the girls were growing up.

So we had pictures of them, and on the back of every picture, my grandfather always wrote, "Uncle Shmiel killed by the Nazis," or, "Aunt Ester killed by the Nazis."

So I always wondered, "Why are there no stories about these people?"

♪ ♪ [Adolf Hitler speaking German] [Cheering] Narrator: In open defiance of the Versailles Treaty, Hitler had built a mighty military machine, then sent his forces to seize the Rhineland, Austria, and the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia.

The Nazis had relentlessly persecuted German and Austrian Jews, reducing their rights, expropriating their property, choking off their livelihoods, declaring them parasites, not citizens... and on the evening of November 9, 1938-- Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass-- Hitler unleashed Nazi mobs on Jews in cities and towns all over the newly expanded Germany, beating, burning, raping, killing, hoping to drive them all out of their country.

Hundreds of thousands of German and Austrian Jews were now desperate to escape the Nazis.

They knew their only hope lay in flight into friendly European countries or across the ocean to the United States.

♪ ♪ [Ship horn blows] Günther Stern: I was getting ready, coming down the stairs, and the newspaper boy of the "St. Louis Star-Times" came along, and he was shouting, "Synagogues burning in Germany.

Read all about it," and, I--I--I--I--I didn't get it at first, and then I--I knew what it meant, and, I--it--it shattered another past-- another part of my past, and that was the first inkling I got of Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass.

Peter Hayes: At every American consulate in Germany, there were Jews seeking refuge because their houses had been pillaged overnight and so forth, and this was reported in American newspapers.

The "Chicago Tribune," which was an isolationist newspaper in the middle of North America, had pictures of burning synagogues in early November 1938.

Deborah Lipstadt: It's on the front pages of American newspapers.

Some major newspapers have it on the front page day after day after day.

People are shocked.

In America, there is a tremendous response, even from those who don't want Jews coming and even from antisemitic sources because while being an antisemite is one thing, but this is a civilized country seemingly going crazy, seemingly completely out of control, and there is tremendous criticism.

This is not merely a Jewish question, a Catholic question, a Protestant question, a political question or a labor question.

It is one, however, that goes to the foundation upon which we have erected the America that has stood all during our political life for the preservation of worldwide civilization.

Any attack on a minority group in any country is an attack on democracy itself.

Sheen: We might almost say that Nazi savagery against the Jew is the straw that broke the camel's back.

[Applause] Narrator: At President Roosevelt's weekly press conference, he said he could "scarcely believe that such a thing could occur in a 20th century civilization" and withdrew his ambassador from Berlin, the only world leader to do so.

Lipstadt: Because of this public response, the Germans make a strategic decision.

There will be--things will only get worse from here, but it's not going to be on the front pages of the newspaper.

Hayes: FDR, who was normally very cautious about his policy, did the one thing in that interval that he could do by executive action.

He said every Jew in America from Germany who was here on a tourist visa could now stay.

Narrator: "It would be a cruel and inhumane thing to compel them to leave," Roosevelt told the press.

"I cannot in any decent humanity throw them out."

But when a reporter asked if there were plans for a "relaxation of our immigration restriction," the president answered only, "That is not in contemplation.

We have the quota system."

Roosevelt had no executive power to change that system.

Only Congress could alter it.

Mae Ngai: The people who thought that immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe should be highly restricted, they were some of the worst white supremacists in the Congress, and they had deep-seated antisemitism, so they were at the forefront of making sure that as little would be done as possible for Jewish refugees.

Man: This country belongs to the people of this country.

I am not willing myself, while hundreds of thousands in this country are hungry, perhaps millions of children underfed, and hordes of young boys and girls coming into active life seeking jobs without ability to get them, to let down the bars.

Senator William Borah.

Narrator: In the midterm elections, Republicans had increased their numbers in both the House and Senate.

The president found himself more dependent than ever on conservative Southern Democratic committee chairmen, all opposed to allowing more refugees.

The public remained overwhelmingly against any change.

The "Christian Century" editorialized that admitting more Jews would just exacerbate what it called, "America's Jewish problem."

Daniel Greene: Two weeks after Kristallnacht, Americans are asked two questions.

"Do you disapprove of this?"

And 94% of Americans say, "Yes, we disapprove of this."

And then they're asked, "So should we let in Jewish exiles from Germany?"

And more than 7 out of 10 say no.

Narrator: In Germany, even some rank-and-file Nazi party members thought the brutality of Kristallnacht had been excessive, but Nazi leaders were more impressed by the fact that no one had lifted a hand in Germany to stop it, and they were unmoved by the outcry overseas.

They decided to make life still more impossible for the hundreds of thousands of Jews still in harm's way.

As what the Nazis called "atonement" for the murder of the German diplomat in Paris that had been the pretext for Kristallnacht, the Jewish community was fined one billion Reichsmarks.

They were made to clean up the rubble of their own houses and businesses and places of worship and pay for it all themselves.

The regime confiscated their radios, canceled their newspaper subscriptions.

It expelled Jewish children from state schools, barred their parents from driving or owning a car, banned Jews from parks, cinemas, theaters, concert halls, and from those few professions that still had been open to them.

Finally, Jewish Germans were banned from running businesses or buying or selling goods of any kind.

Even getting out of the Reich now meant dropping into destitution.

Emigrants were permitted to take with them just 10 Reichsmarks.

Fully 5% of the fast-growing Reich budget would be funded by property looted from Jews.

By the end of 1938, half of all the Jews remaining in Germany had applied for visas to the United States.

Raymond Geist, the senior American diplomat still left at Berlin, feared he knew what was coming next.

"The Germans have embarked on a program of annihilation of the Jews," he wrote to a colleague.

"We shall be allowed to save the remnants if we choose."

On January 30, 1939, the sixth anniversary of his taking power, the Fuhrer stood before the Reichstag and seemed to confirm Raymond Geist's prediction.

[Cheering] Lipstadt: The time to stop a genocide is before it happens, and whether you're talking about World War II or you're talking about Turkey and the Armenians, the time to stop it is before it happens.

So that when Hitler is speaking out and saying these horrendous things and Germany is disenfranchising Jews and conducting things like Kristallnacht, that's the time to take action.

[Horns honking] Susan Hilsenrath: My father had a cousin who lived in the Bronx, and they had a pickle factory, and they figured that maybe they would help them come to the United States, but it was almost impossible because the United States had a quota, and I guess our family didn't fit into this quota.

So my father had to think of some kind of way to get his children into a safe place.

Joseph Hilsenrath: Our parents told us that we had to get out, leave, and that they would follow us and that we would go to, to France, where people would take children out of the country for money.

Susan: My father had heard of this lady, a French lady, who smuggled children across the border into France, and I understand that he gave her all of the money to take my brother and me across the border.

I was almost 10 years old by then, and my brother was 8, and...

I remember it vaguely because the horror of being separated from my parents, I have pushed it way in the back of my mind.

I can't remember how we got to the train station and how we said good-bye to them, but all I know now is, I mean, I'm a mother and I'm a grandmother, and the idea of--of sending my children away is--is--is--is un-- is unbelievably horrible.

I can't even imagine doing that.

♪ [Artie Shaw and Billie Holiday's "Any Old Time" playing] [Cheering and applause] ♪ Stern: There were, I guess, 3 elements that were my pathway to America.

One was baseball, and secondly, it was music.

I'd never heard jazz before... ♪ and the third entrance was through a girlfriend.

We walked arm in arm, and those beautiful American songs, they were washing over us, and we were singing and feeling good at the few moments I had of that relaxing moment when I became somewhat more American.

Holiday: ♪ Any old time you want me ♪ ♪ I am yours ♪ ♪ For just the asking, darling ♪ ♪ Any old time... ♪ Narrator: Günther Stern's girlfriend Ida Mae Schwartzberg had trouble pronouncing his name.

Stern: My name, at school, was still Günther.

My girlfriend said, "I can't pronounce it.

"That's a tongue twister.

"I'll leave you the first two letters of your name "and add a 'y', and that's what I will call you--Guy."

Heh!

Man: Dear Günther, We have been waiting for a letter from you for so long.

It is comforting to hear from you, even if you have yet to accomplish anything for us.

Please pull out all the stops, dear Günther, so we can all be reunited.

Narrator: Every few months, Guy received a letter from his parents back in Hildesheim, Germany, sometimes including photographs of his family.

Stern: It really shows that one person is missing in there.

Where the hell am I?

I belong there.

Narrator: Guy tried again and again to find someone willing to put up a guarantee of as much as $5,000 to sponsor his family's coming to the United States-- more than 3 times the average annual income of an American worker.

He had no luck.

Stern: And then, a miracle happened.

Narrator: One Friday, hitchhiking to work, he was picked up by a man in a fancy car, who after hearing his story offered to help.

Guy immediately set up an appointment for them to meet with a lawyer who had helped other families obtain affidavits of support.

Stern: We went there on a Saturday morning, and the lawyer, a pompous, supercilious man, said, "And what's your occupation?"

And he said, "I'm a gambler."

And the lawyer said, "We can stop right here.

"It says in the law, the person furnishing "the affidavit has to be a well-established, highly reputed person of the community."

And I said, "Well, couldn't we say something like, 'businessman'?"

This lawyer rose to his full height.

"And deceive the U.S.

Government?"

And he added something else that was insulting.

The man took his hat and walked out.

My great chance... rested on one damned lawyer.

Here, a Jewish lawyer who saw all the niceties of the law and not the dilemma of life and death, which I had spread out.

[Laughter] Newsreel announcer: 200 boys and girls wave a greeting to England, land of the free.

They are between the ages 5 and 17.

The advance guard of the first 5,000 Jewish and non-Aryan child refugees from Germany have been provided with a temporary home here while arrangements are made for them to emigrate.

Narrator: After Kristallnacht, Britain had allowed 10,000 children-- but not their parents-- to escape Nazism in what was called the Kindertransport.

Newsreel announcer: And the youngsters tuck in as if they hadn't a care in the world.

Narrator: In February 1939, Democratic Senator Robert Wagner of New York and Republican Congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers of Massachusetts introduced a new bill.

Greene: The bill says, "Let's let in 10,0000 kids between the age of 5 and 14 per year," 1939 and 1940, and, "Let's not count them against the immigration quota system."

Narrator: The First Lady backed the bill.

Her husband privately offered advice on how it might be passed but said nothing in public, but the American Legion, the Daughters of the American Revolution, and the American Coalition of Patriotic Societies were all opposed.

They had favored some of the 60 bills that had recently been introduced to reduce immigration quotas.

Nell Irvin Painter: It's a xenophobic refusal.

I can't explain it because it seems so cruel to me, especially given a country as big as the United States with plenty of space.

I do understand it in terms of antisemitism.

I don't want to understand that antisemitism could be so deep and so cruel.

Father Coughlin: If I know the American public who fought the League of Nations propagandists... Narrator: Father Coughlin called for the creation of a national "Christian Front" to combat the influence of what he called "Communistic Jews" and claimed to his vast radio audience that Jewish businessmen were firing their Christian employees to make room for Jewish refugees.

Coughlin: There is still the United States Senate with whom these forces must contend... Lipstadt: The restrictionists-- the people who want to restrict immigration-- the isolationists, the antisemites come out of the woodwork.

Democrats, Republicans, people say things like, "Well, 10,000 ugly children will grow into 10,000 ugly adults."

Woman as Eleanor Roosevelt: What has happened to us in this country?

We have always been ready to receive the unfortunates from other countries, and though this may seem a generous gesture on our part, we have profited a thousand-fold by what they have brought us.

Eleanor Roosevelt.

Narrator: No group was more adamantly opposed to admitting Jewish refugees than the German American Bund.

[Drums tapping] 20,000 members would fill Madison Square Garden on Washington's Birthday.

They were led by Fritz Kuhn, a German immigrant who fancied himself the "American Fuhrer."

[Applause] [Applause] [Louder applause] Narrator: Other speakers railed against the president "Frank D. Rosenfeld" and his "Jew Deal."

Kunze: We only call upon our leaders to awake to the fact that the Jew is as alien in body, mind, and soul as any other non-Aryan and that he is a thousand times more dangerous to us than all the others by reason of his parasitic nature.

[Cheering and applause] [Audience members chanting, "Heil Hitler!"]

Great floods of tears for a few hundred thousand job-taking so-called poor Jewish refugees, who incidentally in general... [Booing] have more of this world's goods than you or I will ever possess.

[Applause] Narrator: A "Fortune" magazine poll found that only 1 in 10 respondents favored increasing quotas or making exemptions for refugees, and 4 out of 10 believed Jews had "too much power in the United States."

It further found that 85% of American Protestants and 84% of Catholics opposed offering sanctuary to European refugees.

So did more than a quarter of Jewish Americans.

During hearings on the bill to admit some refugee children, a witness said that it should be passed because it was true to the American tradition of providing sanctuary for religious and political refugees.

New York Congressman Samuel Dickstein gently corrected him.

"This is the form of our government, "but as a matter of fact we have never done the things we preach.

We talked about it."

Hayes: The advocates of that bill, the people who submitted it, withdrew it, and they withdrew it because they thought if it comes to the floor it will open the way to other proposals to utterly stop all immigration into the United States.

In 1939 for FDR, the most important political challenge he faced was getting the Congress to revoke the neutrality acts, the acts that restricted our ability to supply other countries if they became involved in a war with Nazi Germany.

The relaxing of the immigration quotas was less important to him than that.

To us looking back, we tend to think that the most important thing was the humanitarian crisis of the time, but of course if FDR had not succeeded in repealing the neutrality acts in 1939 and 1940, we might think otherwise.

Mendelsohn: My grandfather, Abraham Jaeger, he emigrated with his older sister from this small town in Poland.

My grandfather always, you know, prided himself once he got his citizenship on being an American.

He celebrated everything, the Fourth of July, Thanksgiving.

He loved it.

Narrator: Abraham Jaeger's older brother Shmiel had not loved America.

He had arrived in New York back in 1912, quickly saw that the teeming streets of the Lower East Side were not paved with gold.

Woman: Shmiel saw the pushcarts on Delancey Street.

The Jews who lived down in those Jewish areas was not his style.

He was a gentleman, and he says, "At home, I have vineyards "and orchards and a beautiful house.

What do I need America?"

[Dog barking] Narrator: After less than a year, Shmiel Jaeger decided to return to his hometown Bolechow in eastern Poland.

Eventually he married his sweetheart Ester, became a successful butcher, and had 4 daughters-- Lorka, Frydka, Ruchele, and Bronia.

Marlene: Shmiel was the oldest brother, and there was respect and reverence.

They called him the mayor of the town.

He was exceedingly handsome, and then they had all those darling children.

Mendelsohn: My grandfather used to say with a sigh, you know, "My older brother wanted to be a big fish "in a small pond, so he went back to Bolechow, and he was a big fish in a small pond."

And that was the right decision for him, as strange as that sounds, knowing what later happened.

Narrator: In the late 1930s, antisemitism intensified in Poland.

The Catholic Church and the right-wing government promoted boycotts of Jewish businesses.

Politicians pressured Poland's Jews to leave the country.

Gangs attacked their Jewish neighbors.

Thugs threatened Shmiel on the street.

Hanging over everything was the growing possibility of a German invasion, which would surely make life far more harsh.

Man: From reading the papers, you know a little about what the Jews are going through here, but what you know is just one one-hundredth of it.

When you go out into the street or drive on the road, you're barely 10% sure that you'll come back with a whole head or your legs in one piece.

Shmiel.

Narrator: "I know that in America life doesn't shine on everyone," he wrote to his relatives back in the United States.

"Still, at least they aren't gripped by constant terror."

[Crowd cheering] On March 15, 1939, German troops marched into Prague, the capital of what remained of Czechoslovakia.

100,000 more Jews now fell into Hitler's hands.

Hitler's promise of peace to Britain and France at Munich had lasted less than 6 months.

"In a fortnight," he said, "no one will give it any thought."

It was clear that Poland would be his next target.

Hitler was sure that France and Britain would not dare intervene there either.

"Our enemies are little worms," Hitler said.

"I saw them at Munich."

This time, Hitler was wrong.

Britain and France finally saw the folly of trying to appease him further.

If he attacked Poland, this time they would fight back.

[Train whistle blowing] With war more likely than ever, more and more Jews were desperate to get off the continent.

Sol Messinger: It was very difficult to get a visa to the United States, so our family decided that we would try to go to Cuba, mainly, I guess, because it was close to the United States.

Narrator: The Cuban government was now selling refugees tourist visas that allowed them to land on the island and stay until their turn came to emigrate to the United States.

Messinger: My mother finally managed to get a Cuban visa and tickets to go on the St. Louis, but then the problem was my father was still in Poland.

He had been deported back.

My mother wrote him.

She said she had the visas, but she wasn't going to leave unless he could join us, and he wrote back, "Leave unless you want your son's blood on your hands."

The day before we were supposed to leave for Hamburg, there was a knock on the door, and my mother screamed because she recognized my father's knock.

Ran to the door, opened the door, and my father was there.

He had gotten permission from the German government to come back to Germany for two days so we could leave together.

So the next day, we went to Hamburg, and we got on the ship, the St. Louis.

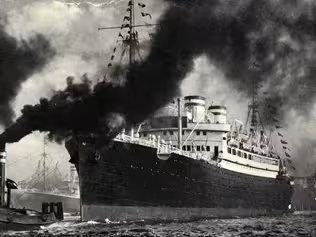

Narrator: The St. Louis left Hamburg on May 13, 1939, one of many ships carrying passengers anxious to escape the coming storm.

More refugees got on at Cherbourg.

Almost all of the 937 passengers were Jewish, most from Germany, some from Eastern Europe, and still others, like the Messingers, now officially "stateless."

Messinger: We all were standing at the railing, looking at Germany getting a little and farther and farther away, and my father started crying, and my mother looked at him, and she says, "What are you crying about?

We're finally together, you're--we're leaving Germany," and he said, "Well, of course, you're right, "but I'm crying because we're leaving "so many of our relatives here, and God only knows when we'll see them again."

Narrator: They traveled in comfort, dining, dancing, sunbathing, swimming in the ship's pool.

The liner's captain Gustave Schröder was an anti-Nazi.

He saw to it that a portrait of Hitler was taken down during Friday night prayers and insisted that his crew treat his passengers with a kind of courtesy no Jewish person was afforded then anywhere under Hitler's control... [Ship horn blowing] but when the ship reached Havana, it was clear that something was wrong.

Only 28 passengers were allowed to come ashore.

All the rest, over 900 people who had paid a corrupt Cuban official back in Germany thousands of dollars for their tourist visas, were ordered to stay on board.

Messinger: The next day, it turned out that we were told that Cuba had invalidated our visas.

We had paid for them, we had gotten them, we had gotten to Cuba only to find out that they had invalidated our visas.

Narrator: Things had changed in Cuba since the St. Louis set sail.

Antisemitism had always been strong on the island, and some 4,000 mostly Jewish refugees had settled there in recent months.

5 days before the St. Louis sailed, 40,000 Cubans had gathered in Havana to protest their presence.

Nazi agents encouraged rumors that the refugees would take Cuban jobs.

The largest Cuban newspaper's headline demanded "Out with the Jews!"

Under the pressure, the Cuban government reneged.

For 6 days, friends and relatives who had come to Cuba earlier circled the ship in small boats, passing up fresh food and shouting what encouragement they could.

Finally, the Cuban government ordered the St. Louis out of Havana Harbor.

For 4 days, the ship steamed aimlessly along the Florida coast, her stunned passengers unsure where they were now to go.

Messinger: I remember it was dusk, and my father and I were standing at the railing, and I saw some lights in the distance, and I said to my father, "What are those lights?"

And he said, "Oh, that's a city in the United States called Miami."

So I've--I've been in Miami since then, and whenever I walk along the beach and look out at the water, I get this very strange feeling because now I'm where I was dying to be in the--in 1939.

Narrator: Some on board the ship wired an appeal to President Roosevelt, begging him to intervene.

They did not receive a reply.

Instead, the State Department insisted that the passengers would have to "Wait their turns "on the waiting list and qualify for and obtain "immigration visas before they may be admissible into the United States."

That could take years.

Canada wouldn't take them either.

The St. Louis turned back toward Europe.

Man: The "New York Times."

The saddest ship afloat today, the Hamburg-American liner St. Louis, with 900 Jewish refugees aboard, steaming back toward Germany after a tragic week of frustration.

No plague ship ever received a sorrier welcome.

At Havana, the St. Louis' decks became a stage for human misery.

There seems to be no help for them now.

The St. Louis will soon be home with her cargo of despair.

Narrator: A Nazi journal gloated.

"We say openly that we do not want the Jews "while the democracies keep on claiming that they are "willing to receive them and then leave the guests out in the cold!"

"The resolve of most of the people aboard," one passenger wrote, "is to die rather than to see Hamburg again."

Captain Schröder considered running his ship aground somewhere off England or France, anything to keep the passengers from having to return to Germany.

A private relief organization called The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, along with The Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees, negotiated furiously with European governments, trying to get them to accept the passengers.

They managed to scrape together the enormous sum of $500,000 and finally convinced England, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands to take them all in.

"Our gratitude is as immense as the ocean on which we are now floating," the passengers cabled to those who had arranged their rescue.

The St. Louis would dock in Belgium, not Germany.

Messinger: We got word that 4 countries in Europe had agreed to split the passengers up among them, and we ended up in Belgium.

Narrator: No one aboard the St. Louis was returned to Germany, but 254 of the passengers would be murdered after the Nazis overran the countries that had given them sanctuary.

Nearly 3/4 of the passengers would survive.

[Newsreel announcer speaking Russian] Narrator: On August 23, 9 weeks after the St. Louis returned to Europe, the world was stunned by an announcement from Moscow-- the Nazi and Soviet governments-- sworn enemies for years-- had signed a 10-year non-aggression pact that would let Hitler and Stalin destroy Poland and divide its territory between them.

Poland was home to 3,300,000 Jews.

[Air raid siren] [People shouting] On September 1, 1939, Hitler launched his "Blitzkrieg," his "lightning war," on Poland.

[Explosion] The Second World War had begun.

"It's come at last," President Roosevelt said when he was awakened with the news.

"God help us all."

As German warplanes attacked Warsaw that evening, Chaim Kaplan, the director of a Jewish school in that city, made a note in his diary.

"We are witnessing the dawn of a new era in the history of the world," he wrote.

"This war will indeed bring destruction "upon human civilization.

"As for the Jews, their danger is 7 times greater.

"Wherever Hitler treads, there is no hope for the Jewish people."

Roosevelt: This nation will remain a neutral nation, but I cannot ask that every American remain neutral in thought, as well.

Even a neutral has a right to take account of facts.

Even a neutral cannot be asked to close his mind or to close his conscience.

Narrator: The president and most of his fellow citizens sympathized with the Nazis' victims, and some wanted to help France and England as they went to war against Germany, but a far larger number was still opposed to any American involvement overseas for fear the Allies would pull the United States into another war.

Roosevelt: And that I hate war... Narrator: Roosevelt was careful not to get too far ahead of public opinion.

Roosevelt: I hope the United States will keep out of this war.

I believe that it will, and I give you assurance and reassurance that every effort of your government will be directed toward that end.

Narrator: The United States was poorly prepared for conflict in any case.

The segregated army was smaller than that of Bulgaria, fewer than 190,000 men in uniform, fitted out with tin hats and leggings issued during the Great War and carrying rifles designed in 1903.

Meanwhile, the president believed the best way to avoid having to enter the war was to do all he could to aid France and England.

He called Congress into special session and asked it to end the embargo on the sale of arms to belligerents so that the Allies would be better prepared for whatever Hitler did next.

Isolationists flooded Washington with antiwar messages.

After 6 weeks of sometimes bitter debate, Congress did lift the embargo but only if buyers paid cash.

That same month, a "Fortune" magazine poll found that only 20% of Americans favored aiding the European democracies while 54% of the country were happy for the United States to trade with Nazis and democratic governments alike.

"What worries me," FDR wrote to a friend, "is that public opinion over here is patting itself "on the back every morning thanking God for the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans."

[Radio stations changing] Charles Lindbergh: I speak tonight to those people in the United States of America who feel that the destiny of this country does not call for our involvement in European wars.

Narrator: There was another voice on the radio now, too, the voice of the only American whose fame approached Roosevelt's, the celebrated aviator Charles A. Lindbergh.

His message was very different.

Lindbergh: These wars in Europe are not wars in which our civilization is defending itself against some Asiatic intruder.

This is not a question of banding together to defend the white race against foreign invasion.

We must not permit our sentiment, our pity, or our personal feelings of sympathy to obscure the issue, to affect our children's lives.

We must be as impersonal as a surgeon with his knife.

Narrator: Lindbergh had first visited Germany in 1936 at the invitation of the American military attaché in Berlin, who was eager to glean information about the fast-growing Luftwaffe.

He returned two more times.

The Nazis did everything they could to impress him, awarding him the Service Cross of the German Eagle... and Lindbergh was impressed.

He admired the regime's virility and emphasis on order.

His wife Anne thought Hitler "a very great man" maligned by what she called "Jewish propaganda."

The couple had even considered moving to the leafy Berlin suburb of Wannsee until Kristallnacht made them rethink.

"My admiration for the Germans is constantly being dashed against some such rock as this," Lindbergh wrote privately.

"I do not understand these riots.

"It seems contrary to their sense of order and intelligence.

"They have undoubtedly had a difficult Jewish problem, but why is it necessary to handle it so unreasonably?"

On his voyage home from Europe in 1938, Lindbergh had been irritated by the number of Jewish refugees among his fellow passengers.

"Imagine the United States taking these Jews in addition to those we already have," he'd written in his diary.

"There are too many places like New York already.

"A few Jews add strength and character to a country, "but too many create chaos, "and we are getting too many.

This present immigration will have its reaction."

Lindbergh: Our bond with Europe is a bond of race and not of political ideology.

It is the European race we must preserve.

Political progress will follow.

Racial strength is vital, politics, a luxury.

If the white race is ever seriously threatened, it may then be time for us to take our part in its protection, to fight side by side with English, French, and Germans, but not with one against the other for our mutual destruction.

Narrator: "If I should die tomorrow, I want you to know this," the president told a friend.

"I am absolutely convinced that Lindbergh is a Nazi."

For the next 27 months, Franklin Roosevelt and Charles Lindbergh would engage in a bitter struggle over whose vision of the country would prevail and about the future of Western civilization itself.

[Bombs whistling] [Explosion] "Every war costs blood," Hitler had told his commanders just before sending them into western Poland, "and the smell of blood arouses "in man all the instincts which have lain within us "since the beginning of the world.

A humane war exists only in bloodless brains."

There was nothing bloodless, nothing humane, about the German assault.

In the wake of the Panzer divisions that pierced Poland's defenses, thousands of SS troops and German infantrymen fanned out across the countryside.

Their goal was to destroy the Polish state and reduce the Polish people to a leaderless population of peasants and workers.

Told that anyone who dared resist the advancing master race was guilty of "insolence," within 5 weeks they had killed some 3,000 Polish prisoners of war, destroyed more than 530 villages, burned or blown up synagogues, and murdered at least 45,000 unarmed Poles-- priests, professors, political leaders, anyone thought capable of mounting resistance, as well as Jews, and while the Germans imposed their rule on western Poland, the Soviet Union swallowed up its eastern half.

150,000 Poles were drafted into the Red Army.

The Soviets shipped 200,000 civilians deemed dangerous to Kazakhstan and Siberia, where tens of thousands froze or starved to death.

They also secretly shot 22,000 Polish officers and intellectuals and buried their corpses in mass graves in and around the Katyn Forest.

Hitler's goal was always a racially "pure," steadily expanding Greater Germany, but as it expanded, it inevitably encompassed more and more Jews.

Before the invasion, Poland had the highest proportion of Jews in Europe.

Nearly two million of them lived in the region Germany had seized.

Most were people without means and access to diplomats or consulates or well-connected family members abroad or anyone else who could help them escape.

More Jews lived in Warsaw than remained in Germany.

More lived in the city of Lodz than in Berlin and Vienna combined.

Nazi officials hatched several schemes to rid the region of its Jews.

The first would have confined them to a "reservation" located in a remote underpopulated area near Lublin, but that quickly proved impractical.

The Nazis offered two million of them to Stalin, who did not want them.

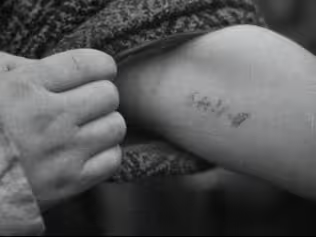

In the meantime, the Germans were driving Polish Jews into scores of squalid, congested, fenced-off neighborhoods-- ghettos--whose residents, robbed of their possessions and forced to wear a yellow star or a white armband with the Star of David, were shot if they strayed outside.

The largest ghetto was in Warsaw, where more than 400,000 men, women, and children struggled to survive in an area initially measuring less than two square miles.

The ghettos served two purposes for the Nazis.

They provided reliable pools of slave labor for the German war machine, and they acted as holding pens for Jews, now including many deported from what had been Austria and Czechoslovakia, until the Nazi regime decided where they were finally to be sent.

More than 80,000 people would die in the Warsaw ghetto alone of random shootings by their German guards, typhoid, deliberate starvation, and despair.

In Bolechow, in eastern Poland, Shmiel Jaeger heard about the German obliteration of western Poland.

Terrified of what might happen next, he wrote again to his relatives in America.

Man as Shmiel: My darling sister and brother-in-law, This is my mission: it's now the case that many families can go and have already emigrated to America provided that their families there put down a $5,000 deposit, after which they can get their brother and his wife and children out, and then they can get the deposit back.

Perhaps you could manage to advance me the deposit.

The idea is that with the money in custody I won't, once I'm in America, be a burden to anyone.

You should make inquiries, you should write that I'm the only one in your family still in Europe and that I have training as an auto mechanic and that I've already been in America from 1912 to 1913.

For my part, I am going to post a letter, written in English, to Washington, addressed to President Roosevelt and will write that all my siblings and my entire family are in America and that my parents are even buried there.

Perhaps that will work, as I really want to get away from this Gehenim with my dear wife and such darling 4 children.

Shmiel.

Narrator: Shmiel had no way of knowing that there were more than 100,000 other Poles ahead of him on the waiting list.

With the current quota system, it would be more than 12 years before his family would be eligible for a visa.

Marlene: We knew, we--we all understood that there was big trouble.

It was very sad.

My mother would send clothing or whatever they would need for the winter, and all of the family was involved because they were all here and all feeling guilty that Shmiel had not come.

They were all trying to get money together to send.

They met, they talked to the richer members of the family, and everyone was concerned, but no one could do anything.

Mendelsohn: My grandfather was a foreman in a braids and trimmings factory.

I'm sure if he had $5,000 he would have done anything, but I think it's also an important part of this story, this sort of guilt, the huge amount of guilt in the American Jewish community after because then, of course, you say, "Oh, I should have done more," but, again, that's not fair.

People really had a hard time imagining what was actually going to unfold.

Narrator: As soon as German troops had occupied Vienna in 1938, Eva Geiringer's father Erich had resolved to find his wife Fritzi, his son Heinz, and daughter Eva a new home out from under the Nazi threat.

By early 1940, he had managed to get them to Amsterdam.

Eva Geiringer: The Dutch were quite different from the Austrians-- very welcoming.

Everybody wanted to be my best friend.

I was blonde and blue-eyed, and so everybody said, "You look like a Dutch little girl."

So we settled in, and we thought, "Well, that is it.

We'll be here together as a family," and we were actually quite happy.

Narrator: The Geiringers found themselves living in the same apartment block as Otto Frank, his wife Edith, and their two daughters Margot and Annelies.

The Franks had fled Germany 6 years earlier.

Geiringer: All the children came to play after school on this big open area, and then, one day, a little girl came to me, realized I was new there, and she introduced herself and said her name is "Anna Frank."

Narrator: Both Eva Geiringer and Anne Frank were 10 years old that winter and both attended the same Montessori School.

Geiringer: She was very, very much outspoken, very sure of herself.

She was definitely already more intellectual than I was.

She was a big chatterbox.

In school, she was called "Mrs.

Quack-Quack."

She had to stay behind very often to write hundreds of lines that she's not going to talk so much in class.

She was already interested in boys.

When I told her I had an older brother, her eyes grew very big, and she said, "When can I come and meet him?"

Narrator: Anne Frank's father tried to stay optimistic about the future, reminding everyone that the Netherlands had been able to remain neutral during World War I and should be able to do so again, but he could not hide his underlying anxiety from a cousin, who was now living safely in London, writing her that he worried most about his daughters but didn't dare confide his concern to their mother.

His cousin offered to care for them in England.

He thanked her for her kindness but was sure neither he nor his wife could bear to part with their girls.

Otto Frank was still waiting for his family's visa application to the United States to come up for review.

More than 300,000 other people were waiting, too.

A 7-month lull followed the invasion of Poland.

To American isolationists, it seemed to be proof that events in Europe were nothing to worry about.

Republican Senator William Borah of Idaho called it the "Phony War"... [Bicycle bell rings] [Airplanes flying] but on April 9, 1940, the Phony War became real again.

40,000 German troops surged across the Danish border.

Denmark surrendered by nightfall.

German paratroopers filled the skies over Norway, driving its government into exile.

Then, on May 10, 10 Panzer divisions, 2,500 aircraft, and 3 1/3 million German ground troops stormed into France and the Low Countries-- Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands.

We heard guns shooting and the drones of airplane, and we all got up, and we had a little Bakelite radio.

Newscaster: The German army invaded Holland and Belgium... Geiringer: Listened to that, and the newscaster said, "Very bad news.

"The Germans are trying to invade our country, but we are going to defend ourselves."

Narrator: At Otto Frank's office, his employees remembered, his face turned white as reports of the attack continued to come in over the radio.

The Germans threatened to bomb the port of Rotterdam unless the Dutch surrendered.

They tried to surrender... and the Luftwaffe bombed the city anyway.

Over 900 people were killed and more than 85,000 left homeless.

The United States consulate was burned, too, and with it, Otto Frank's application for visas to bring his family to America.

Every port the Germans overran closed off yet another avenue of escape for refugees.

France was next.

Its supposedly invincible 5-million-man army would collapse in just a few weeks.

[Gunfire] [Man shouting in German] Roosevelt: Tonight over the once peaceful roads of Belgium and France, millions are now moving, running from their homes to escape bombs and shells and fire and machine-gunning, without shelter, and almost wholly without food.

They stumble on, knowing not where the end of the road will be.

Narrator: "These are ominous days," Roosevelt told Congress on May 16, "days whose swift and shocking developments force every neutral nation to look to its defenses."

He called for an increase in aircraft production from 2,100 planes a year to 50,000.

To isolationists like Charles Lindbergh, the president and other unseen forces were taking another step toward U.S. involvement in the war.

Lindbergh: The only reason that we are in danger of becoming involved in this war is because there are powerful elements in America who desire us to take part.

They represent a small minority of the American people, but they control much of the machinery of influence and propaganda.

They seize every opportunity to push us closer to the edge.

It is time for the underlying character of this country to rise and assert itself, to strike down these elements of personal profit and foreign interest.

Narrator: A week later, battered British and Belgian troops, along with what little was left of French forces, began fleeing across the English Channel from Dunkirk, leaving behind tons of arms and materiel.

The United Kingdom now stood alone.

Many on both sides of the Atlantic agreed with the assessment of Roosevelt's ambassador in London Joseph P. Kennedy.

"Britain," he said, "is doomed."

Susan: My brother and I, we were in one of the crowds when the Germans came marching in, and all I knew is we had to hurry up and get away.

Narrator: Susan and Joseph Hilsenrath's parents had arranged for them to be smuggled out of Germany into France, where the children had endured a precarious sanctuary for 8 months.

They hoped their parents had also gotten out of Germany.

In fact, they had managed to get visas and make it to America, first the father and then their mother and baby brother several months later, but Susan and Joseph weren't sure where they were or how they would be reunited.

They had lived with a young cousin in Paris, then with a series of foster families until June 14 when the Germans had entered the city.

[Marching footsteps] Susan: Everybody was going on the bus, on bicycles and cars and walking, trying to get out, to get to Versailles.

All of these people marched to the-- to the palace, and the mayor of the town, he got the idea of giving everybody a burlap sack.

They have these beautiful gardens in the back of the palace, and way in the corner, they had a big haystack, and so all of the people took their burlap sack and filled it up with hay.

Then we had a mattress.

We took our mattress, and we all walked into the palace, and there's this beautiful room called the Hall of Mirrors, and we slept in the palace.

For a few days, we were there, and everything seemed to be fine, but then we heard that same sound of the marching.

We heard tanks, and we saw people going on motorcycles, and there was a one car at the head of this caravan, and out came a German officer, and he wanted to talk to the mayor of the town, and he did not know how to speak any French, and the mayor of the town did not know how to speak any German.

So somebody in the crowd says, "Oh, there's "this girl who's in the palace, and she knows how to speak German."

I was standing there, and I looked at this-- at this German officer.

He was as tall as the ceiling, and--and--and-- and I was so afraid, but at the end of the conversation, the Nazi officer bent down to me, and he said, "Little girl, how come you know how to speak German so well?"

And I said to him, "The French schools "are really very good, and I learned how to speak German in the French schools."

And so he clicked his heels, and he shook my hand, and he walked away.

Narrator: With Hitler's conquest of Poland and western Europe, President Roosevelt had understood that the ongoing refugee crisis was sure to turn into a catastrophe.

"It is not enough to indulge in horrified humanitarianism, empty resolutions, and pious words," he said.

Safe havens had to be found quickly for these "desperate people."

Before war broke out, he had been unwilling to go against public opinion and call for American immigration quotas to be expanded, in part because he knew if he did so Congress might well close them off altogether.

Behind the scenes, he had pressured Latin American countries into accepting some 40,000 Jews in flight from Hitler, but no other nations had proved any more welcoming to refugees than they had been before the Second World War began, and now, Roosevelt and much of the American public had begun to view would-be immigrants differently, not as victims but as potential threats to the security of the United States.

Man: You'd think from the number of spies they've been sending over here that we're at war with Germany.

It looks more as if Germany were at war with us.

Narrator: "Confessions of a Nazi Spy," made by Warner Bros., the only movie company to have pulled out of Germany rather than do business with Hitler's regime, was the first overtly anti-Nazi film made by a major Hollywood studio.

The movie was based loosely on the story of a real German spy ring broken up by the FBI, and it captured a growing sense of public panic.

The sudden terrifying swiftness with which the Western European democracies collapsed under Hitler's assault led many to assume he must have had help from within.

The American ambassador to France claimed the collapse of that country had been in part the work of native Communists and Nazi agents, some of whom, he alleged, had entered the country as Jewish refugees.

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover said the bureau was now receiving 3,000 tips about possible espionage every day, and hired 150 more agents to seek out Nazi spies, who were called Fifth Columnists.

Martyn: And the government alleged just conspired to provide secret information to an unnamed foreign government.

Lipstadt: A country can be attacked from 4 sides, but there's actually a fifth side from which it can be attacked, and that's from within, if you have spies in your midst.

There's a great fear that the Germans are sending over spies, and they were.

There were spies for Germany.

But the fear of spies intersects with the antisemitism.

The fear of spies intersects with the anti-immigration, anti-refugee sentiment.

Narrator: The "New York Herald Tribune," one of the most respected newspapers in America, claimed that 42 Nazi agents had supposedly been recruited from among German "half" Jews and "quarter" Jews.

The "Saturday Evening Post" charged that Nazi spies passing as refugees had infiltrated Europe and America.

Less than 3% of Americans believed Washington was doing enough to combat subversion.

In the summer of 1940, an Alien Registration Act sailed through Congress, requiring non-citizens over the age of 14 to be registered and fingerprinted and sharply curtailing their rights to free speech and political participation.

"Something curious is happening to us in this country," Eleanor Roosevelt wrote in her column, "and I think it is time we stopped "and took stock of ourselves.

"Are we going to be swept away from our traditional attitude toward civil liberty by hysteria about 'Fifth Columnists'?"

But the president told the press that he had been told that in several countries Jewish refugees had become spies for the Germans, involuntary spies, he explained, because if they didn't agree to spy, the Nazi government back home had told them, "We are frightfully sorry, "but your old father and old mother "will be taken out and shot.

Of course," the President continued, "it applies to a very, very small percentage of refugees coming out of Germany."

Lipstadt: Of course, a refugee would be the worst person to be a spy.

A refugee doesn't speak the language, speaks the language with an accent.

A refugee doesn't know the ways to work their self into the woodwork and not be noticeable.

But nonetheless, there is this irrational fear.

No one says a nation should let people in that is going to harm it or weaken it, but the evidence was nonexistent.

Narrator: Assistant Secretary of State Breckinridge Long and many of his colleagues thought, without evidence, that Jewish refugees were especially dangerous.

A wealthy contributor to Roosevelt's first presidential campaign, Long had served for 3 years as FDR's ambassador to Italy and was semi-retired when Roosevelt called him back to government service to run the Visa Division.

Hundreds of thousands of desperate people, most of them Jews, were already on the waiting list for American visas, and more were lining up every day.

Long was unmoved.

To him, every train or ship carrying Jews out of Nazi Europe represented what he called, "a perfect opening for Germany to load the United States with Nazi agents."

Long's goal, he confided to his diary, was "practically stopping immigration."

Lipstadt: Breckinridge Long is working every which way to prevent Jews from coming into this country.

When people are desperate to get out, he is amongst those helping to create the barriers.

Narrator: Long especially loathed Rabbi Stephen Wise, whom he found sanctimonious, because he spoke so often of the courage of men and women fleeing from torture by dictators.

"Only an infinitesimal fraction are of that category," Long noted in his diary.

Greene: One of the lessons of this history is something else was always more important for the Americans than aiding Jews.

But we see some Americans who don't respond that way.

Woman: If I'd been a man, I would have joined the Navy and seen the world, but since I was a woman, I joined the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee.

Laura Margolis.

Narrator: While official American policy remained rigid and restricted, individual women and men working for dozens of Jewish organizations, including the National Refugee Service and the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, did all they could, wherever in the world they could, to help.

They would coordinate loans, legal counsel, ocean liner tickets, and jobs for newcomers.

Without their help, tens of thousands of Jewish refugees would never have made it to America.

They worked alongside other committed Americans from the YMCA, the Unitarian Service Committee, and the American Friends Service Committee.

By the summer of 1940, the focus of their relief and rescue operations was in southern France.

Germany occupied only the western and northern regions of France.

The south was left in the hands of a collaborationist French government with headquarters at Vichy.

Some 50,000 refugees from 42 countries were interned in 93 squalid, overcrowded camps.

Tens of thousands more remained free, trying to keep one step ahead of the French police, who were required to hand over any refugees the Germans demanded.

Scores of eminent artists and intellectuals were thought to be in immediate danger.

To help, a group of prominent writers in New York formed the Emergency Rescue Committee.

Eleanor Roosevelt talked her husband into asking the reluctant State Department to issue a limited number of emergency visitor's visas.

Man: I remembered what I had seen in Germany.

I knew what would happen to the refugees if the Gestapo got hold of them.

I could not remain idle as long as I had any chance at all of saving even a few of its intended victims.

It was my duty to help them.

Varian Fry.

♪ Narrator: Varian Fry, a 32-year-old writer and member of the Emergency Rescue Committee, volunteered to go to France and try to get the refugees out.

He was every inch the Harvard-educated intellectual he appeared to be, but as a foreign correspondent visiting Germany 5 years earlier, he'd witnessed attacks on Jews that left him with a visceral loathing for the Nazis.

He arrived in Marseille on August 15, 1940, with $3,000 in cash strapped to his leg and a list of 200 distinguished women and men thought to be somewhere in Vichy, France.

Man as Fry: It is the non-French refugees among whom one finds the greatest misery.

They are being crushed in one of the most gigantic vises in history.

They have literally been condemned to death here, or at best to confinement in detention camps, a fate little better than death.

Narrator: He took room 307 at the Hotel Splendide and went to work.

News quickly spread that an American with visas had arrived.

Refugees knocked at his door at all hours, filled the hallways, and lined the stairs.

25 letters a day turned up for him at the reception desk.

The telephone rarely stopped ringing.

[Telephone ringing] The American Vice Consul in Marseilles Hiram Bingham Jr. and some of his colleagues were happy to help whenever they could.

Bingham was the son of a senator from Connecticut.

His Groton classmates had called him "Righteous Bingham" for his earnestness.

He, too, had seen Nazi brutality first-hand, and he believed it his duty to obtain "as many visas as I could for as many people," and was sometimes willing to break the rules.

He allowed the fugitive German Jewish novelist Lion Feuchtwanger to hide in his villa and then cooperated in smuggling him out of the country with Reverend Waitstill Sharp, a veteran rescue worker for the Unitarian Service Committee.

In order to emigrate to the United States from Vichy, each refugee required an American immigration visa, visas for neutral Portugal and Spain, a steamship ticket from Lisbon, and an exit visa from France.

Each took time to obtain and each had an expiration date.

By the time the last document was procured, another had often expired, requiring the whole laborious process to begin all over again.

To get around this system, Varian Fry helped to smuggle refugees across the Pyrenees into Spain.

He assembled a staff of 46 volunteers that included refugees, young American men and women, a French gendarme, and a Viennese cartoonist who proved an adept forger of documents and official stamps.

Fry worked closely with American Jewish organizations that provided crucial financial support from Portugal and with sympathetic diplomats from other countries-- Mexican, Brazilian, Siamese, and an especially empathetic Chinese consul, whose formal-looking documents in Mandarin were rarely challenged at the border because neither French nor German officials could read them.

Man as Fry: It's stimulating to be outside the law.

The experiences of 10, 15, and even 20 years have been pressed into one.

Sometimes I feel as if I had lived my whole life.

Narrator: Reports of what Fry was up to eventually reached Washington.

Secretary of State Cordell Hull himself cabled the Marseille consulate that "This Government cannot-- repeat cannot-- "countenance the activities of Mr. Fry and other persons, however well-meaning their motives may be."

The State Department tried to force Fry out of France, but he somehow managed to remain in Marseille for another 7 months until Vichy police escorted him out of the country.

Together, Fry and Bingham, whom Fry remembered as his "partner in the crime of saving lives," are thought to have rescued at least 2,000 people from the Nazis.

Some were the celebrated people Fry had been sent to save, including the harpsichordist Wanda Landowska, the film director Max Ophuls, the sculptor Jacques Lipschitz, the philosopher Hannah Arendt, and the artists Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp, and Marc Chagall.

But also among them were hundreds of men, women, and children who were not well-known, just human beings in need of help.

[Air raid siren] Murrow: Hello, America, this is Edward Murrow speaking from London.

There were more German planes over the coast of Britain today than at any time since the war began.

Anti-aircraft guns were... Narrator: In the summer and fall of 1940, as Britain was under relentless attack from German bombs, President Roosevelt ran for an unprecedented third term.

He would have to persuade voters that, while he opposed American entry into the war, he also needed to provide aid to Britain, as the last, best hope of defeating Hitler, and to ready the United States for conflict if it came, as well.

On September 16, 1940, he signed into law the first peacetime draft in the history of the country.

Roosevelt: To the 16 million young men who will register today, I say that democracy is your cause, the cause of youth.

Narrator: The odds against the democracies had lengthened further.

Germany was now allied with fascist Italy in Europe and Imperial Japan in Asia--the Axis.

Roosevelt's Republican opponent Wendell Willkie, nominated just a few days after France fell, shared Roosevelt's belief that Britain had to be helped.

Now, so did nearly 3/4 of the American people.

Public opinion was slowly beginning to change.

But soon after Roosevelt agreed to provide Britain with 50 old destroyers, Charles Lindbergh became the chief spokesman for a new isolationist organization dedicated to keeping America out of the war-- the America First Committee.

Lindbergh: France has now been defeated, and despite the propaganda and confusion of recent months, it is now obvious that England is losing the war.

I believe... [Cheering and applause] And I have been forced to the conclusion that we cannot win this war for England regardless of how much assistance we send.

That is why the America First Committee has been formed.

Narrator: It was founded by a handful of students at the Yale Law School and run by a National Committee that at various times included General Robert E. Wood, chairman of the board of Sears Roebuck, the head of the United States Olympic Committee Avery Brundage, the automobile magnate Henry Ford, World War I ace Eddie Rickenbacker, Lillian Gish, the star of "Birth of a Nation," and Theodore Roosevelt's daughter Alice Roosevelt Longworth.

The Committee soon had some 800,000 members in 450 chapters all across the country, the largest anti-war organization in the history of the United States.

Despite the opposition, FDR was reelected to a third term and soon proposed a Lend-Lease bill, allowing him to supply Britain with more desperately-needed military and naval supplies.

Roosevelt: I ask this Congress for authority and for funds sufficient to manufacture additional munitions and war supplies of many kinds to be turned over to those nations which are now in actual war with aggressor nations.

Narrator: The bill was designated HR 1776 in hope that voters would see its passage as patriotic.

Isolationists called it the dictator bill.

Charles Lindbergh testified against it.

He favored neither a British nor a German victory, he said, and warned that U.S. entry into the war would be "the greatest disaster this country has ever gone through."

FDR denounced him as an appeaser.

Isolationist and antisemitic groups now flooded the halls of the Capitol to oppose the new bill, including black-clad members of a self-proclaimed "Mothers' Movement" who cursed legislators and insisted that Jews were behind what they believed to be Roosevelt's rush toward war.

Lipstadt: It's not just something that is hypothetical.

England can fall.

Hitler will take over all of the European continent.

And America First fails to see the danger to the world at large.

Tyrants will go as far as you allow them to go.

They're always testing the waters.

Can I go further?

Can I push stronger?

And the America First and the isolationists refuse to acknowledge that.

Narrator: In the end, the Lend-Lease bill passed.

Newsreel announcer: Guns and munitions of all sorts pour into Britain as almost hourly convoys from the States bring their precious cargos.

The original $7 billion of lend-lease aid has already been allocated.

Now Congress studies final passage of another 6 billion, and Britain studies invading the continent with arms made in the U.S.A. Messinger: When the German invasion was over, we were glad we were in Vichy, France, not under the control of the Germans.

There was still an American embassy there.

My father could go there and pursue our visa to the United States.

Narrator: Sol Messinger and his parents, having been turned away from Cuba on the St. Louis, had now managed to escape from Belgium after the Germans invaded.

They made it to a small village in Vichy, France--Savignac.

But after a few months, they were arrested and put in a French internment camp.

Messinger: My father found out that there was an underground, which helped people to escape, so we planned to escape.

My mother and I, it was Christmas Eve, and the French soldiers were drunk, and we simply walked past the French soldiers.

[Train whistle blows] We had decided we would go back to Savignac.

It's the only place that we knew in France.

So we got on a train.

Of course, you were not allowed to be on a train without papers.

Fortunately, nobody asked us for our papers.

But my father was still in the camp.

On New Year's Day, we were standing outside, and in the distance we saw 4 men walking towards us, one of whom was my father.

He had escaped, so we were reunited again.

It was just incredibly lucky.

[Trolley clangs] Narrator: Otto Frank was ordinarily a cautious man, content to keep a low profile and go about his business in Nazi-occupied Amsterdam.

But one day, he made an uncharacteristically incautious remark to a Gentile employee's husband whom he didn't know well.

When the man expressed confidence that Germany would win the war soon, Frank had disagreed.

The man turned out to be a Nazi sympathizer who wrote a letter to the Gestapo denouncing Frank.

A member of the Dutch fascist party intercepted the letter and demanded money to keep quiet about it.

Now, subject to blackmail and fearful that the Germans would come for him and his family at any time, Otto Frank stepped up his efforts to try to get to the United States, despite the fact that his visa application had been destroyed in the bombing of Rotterdam.

In desperation, Frank turned to an old friend--Charley Straus.

Straus knew the Roosevelts, was the administrator of the Federal Housing Authority, and his father had been a co-owner of Macy's department store.

Man: April 30, 1941.

Perhaps you remember that we have two girls.

It is for the sake of the children mainly that we have to care for.

Our own fate is of less importance.

The consul asks a bank deposit of about $5,000 for us 4.

You are the only person I know that I can ask.

Would it be possible for you to give a deposit in my favor?

Who can tell if there is still a chance to leave Europe by the time this letter is going to arrive?

I am still indebted to you, and I shall always be.

As ever, Yours, Otto.

Narrator: Straus and his wife agreed to put up the money, but by that time the State Department had changed its rules.

Consulates had been ordered to deny a visa to anyone with close relatives in Germany or any of the countries it had annexed or occupied out of fear of foreign agents.

Greene: In 1941, you see a series of rule changes that are designed to make it even harder for refugees to get in.

It's not only that it's complicated to line up the paperwork, the State Department is moving the bar on them.

Man: If I had my way, I would today build a wall about the United States so high and so secure that not a single alien or foreign refugee from any country upon the face of this earth could possibly scale or ascend it.

Senator Robert Reynolds.

Narrator: Senator Robert Reynolds of North Carolina, chairman of the powerful Military Affairs Committee charged that Jews were "systematically building a Jewish empire in this country" and called for still more obstacles to immigration.

He also organized a group called the Vindicators to hunt down illegal immigrants.

Meanwhile, in response to President Roosevelt's decision to freeze German and Italian assets in the United States, Germany and Italy ordered American consulates to close in their countries and all the countries they occupied, as well.

Now, for anyone waiting in those countries, there would be no American visas.

Woman: American Friends Service Committee, Rome.

All immigration to the U.S. stopped, thereby robbing many people of their hopes.

They could not understand what difference one day should make and are naturally unable to reconcile themselves to the arbitrariness of laws that affect their whole futures so disastrously.

Another thing that discourages us somewhat is the general attitude of Americans toward the problems with which we have been working.

Really I am so tired of having well-meaning and opinionated people tell me about the Jews and sounding off to the effect of, "Why don't we use all this splendid zeal and energy for some really American activity?"

Marjorie McClelland.

Man: This is not the Second World War.

This is the Great Racial War.

The meaning of this war, and the reason we are fighting out there, is to decide whether the German and Aryan will prevail or if the Jew will rule the world.

Hermann Goering.

[Explosion] Narrator: On June 22, 1941, without any warning to his supposed ally Josef Stalin, Hitler sent 3 vast army groups into the Soviet Union along a thousand-mile front with 3,550 tanks, 2,770 aircraft, and 600,000 horses to haul weapons and supplies across Russia's vast distances.

Hitler's goal was what it had always been, to enslave or eliminate the peoples of Eastern Europe and establish a continental Reich meant to last a thousand years.

The Red Army fell back.

Nearly 6 million Soviet soldiers would fall into German hands during the coming months.

Well over half of them died, most of them worked to death or deliberately starved.

Snyder: Once Germany invades the Soviet Union with the idea of destroying the Soviet Union, mass murder can take place.

To Hitler, the Soviet Union is not a state.

The rule of law does not apply.

This is not even an occupation.

These are just wild territories inhabited by undefined peoples.

When the Germans arrived, the Germans could say, "You've had this terrible period of Soviet oppression.

"And you know who was at fault?

You know who ran it?

It was the Jews."

Narrator: Everywhere, Jews were special targets.

Hayes: They're killing Jews in two ways.

First, they are starving Jews to death in the ghettos that they have established in occupied Poland.

Then they also decide that when they invade the Soviet Union, they're going to shoot people.

Narrator: Specialists were enlisted to follow the advancing army and hunt down and kill Jewish men and partisans who dared wage guerilla war against the invaders, along with other groups deemed to be hostile, inferior, or loyal to the Soviet regime.

3,000 men of the Einsatzgruppen, Operations Groups, were in overall charge, but they were soon reinforced by other killing units-- 20,000 SS men, 30,000 German Order Police, and ordinary soldiers from the German Army.

At first, the Einsatzgruppen encouraged pogroms, sometimes standing by while Latvians, Lithuanians, Poles, and Ukrainians rounded up and murdered their Jewish neighbors.

In scores of cities and towns, Gentiles acting independently also slaughtered thousands of Jews.

♪ ♪ But the Germans soon took over most of the killing themselves.

They shot only Jewish men in the beginning, then started killing women and children who, their officers told them, acted as the partisans' eyes and ears.

Hayes: And they're basically going to round them up as the German armies advance, and they're going to shoot them into ditches, liquidate them in forests, wipe them out.

Narrator: They shot 24,000 Jews at Kamenets-Podolski, 28,000 at Vinnytsia, nearly 34,000 at Babi Yar outside Kiev.

It was all meant to be secret, but many German soldiers carried cameras so that they could send snapshots and home movies to show their families what their husbands and sons and fathers were doing as they moved east.

"Up here in what was Latvia things are pretty Jewified," one soldier told his family, "and in this case no quarter is given."

Snyder: Every photograph we have has to stand in for many, many, many, many other, hundreds of other shooting pits, which are not actually recorded.

These images are taken for purposes, which broaden our sense of horror.

Because it's not just that the event took place and has been recorded.

It's that this is a trophy photo.

And they're horrible in yet another way.

This is typical and not exceptional.

Narrator: One Einsatzgruppen commander remembered the routine.

There were 15-man firing squads.

One bullet per Jew.

One firing squad of 15 executed 15 Jews at a time.

He thought he and his men had killed somewhere between 60,000 and 70,000.

They'd lost count.

Mendelsohn: Two million Eastern European Jews were killed just in what they now call the Shoah by bullets.

I'll never forget a survivor that I interviewed.

He said, "You know, as it was happening to us, "we couldn't believe it, so how was anybody else gonna believe it?"

If they to whom it was happening could scarcely believe the savagery and the sadism and the depravity of what was happening, how are the relatives in America even possibly going to imagine?

Narrator: The Einsatzgruppen eventually reached Bolechow in eastern Poland.

It was home to some 3,000 Jews, including Shmiel Jaeger, his wife, and 4 daughters.

Mendelsohn: These people are now statistics, particularly now, as their individual stories recede, but they were not statistics to themselves.

Every one of them died in a different way.

The third daughter, Ruchele, was taken by herself.

The first roundup in the town happened in the autumn of 1941.

There was a roundup of about 1,000 people.

That was the first action.

And she just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

She was out of the house.

She was walking through the town.

She got caught in this roundup.

These people were held in a local Catholic community center, and people were raped and tortured over about 24 hours.

And then they were taken to a site just outside of the town where there was an old salt mine, and they were all shot.

♪ Man: Vilna, Lithuania.

March 2, 1941.

Elsa, today I'm sending you a postcard.

I want to make sure that maybe you will receive a last postal item from me.

If something happens, I would want there to be somebody who would remember that someone named David Berger had once lived.

This will make things easier for me in the difficult moments.

Farewell.

Narrator: For many months, British intelligence had been decoding top-secret German communications from the front.

In August, the messages were filled with mysterious numbers, which they only gradually realized were evidence of the systematic murder of all the Jews living in every town and village the Nazis overran on the Eastern Front.

Hayes: During the summer of 1941 when the Germans were invading the Soviet Union and liquidating Jews in their path, Winston Churchill got an intercept of the reports that the shooting units were sending back to Berlin.

"Yesterday we shot X number of people."

Then the reports were broken down as time passed to men, women, children, Jews, Communists, so forth.

Narrator: The intelligence continued to come in.

367 shot on one day.

468 two days later.

1,625 the next day.