The World of Cecil Part Two

Special | 56m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Part two continues the examination of the life of Cecil Williams.

Part two continues the exploration of South Carolina's Civil Rights history, guided by the lens and dedication of acclaimed photographer Cecil J. Williams. Beginning with the 1969 Charleston hospital strike, the final major civil rights protest of the 20th century in the U.S., learn how Williams captured his impactful photos.

SCETV Specials is a local public television program presented by SCETV

Support for this program is provided by The ETV Endowment of South Carolina.

The World of Cecil Part Two

Special | 56m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Part two continues the exploration of South Carolina's Civil Rights history, guided by the lens and dedication of acclaimed photographer Cecil J. Williams. Beginning with the 1969 Charleston hospital strike, the final major civil rights protest of the 20th century in the U.S., learn how Williams captured his impactful photos.

How to Watch SCETV Specials

SCETV Specials is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

More from This Collection

Graceball: The Story of Bobby Richardson

Video has Closed Captions

At nineteen years-old, Bobby Richardson, became the starting second baseman for the Yankees. (54m 51s)

Arriving: Leo Twiggs and His Art

Video has Closed Captions

Dr. Leo Twiggs is an artist and educator in South Carolina. (56m 46s)

Video has Closed Captions

The Cleveland School fire of 1923 influenced building and fire codes nationwide. (56m 46s)

Video has Closed Captions

Explore the relationship between Reconstruction and African American Life. (56m 46s)

Video has Closed Captions

Explore the life of acclaimed civil rights photographer, Cecil J. Williams. (57m)

A Conversation With Will Willimon

Video has Closed Captions

William Willimon is an American theologian and bishop in the United Methodist Church. (27m 46s)

Carolina Country with Patrick Davis & Friends

Video has Closed Captions

Carolina Country with Patrick Davis & Friends. (58m 39s)

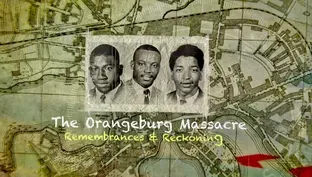

The Orangeburg Massacre: Remembrances and Reckoning

Video has Closed Captions

The Orangeburg Massacre: Remembrances and Reckoning. (56m 46s)

Victory Starts Here: Fort Jackson Centennial

Video has Closed Captions

Celebrating the 100th anniversary of Fort Jackson. (26m 46s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMajor funding for the World of Cecil is provided by the ETV Endowment of South Carolina.

For more than 40 years, the ETV Endowment of South Carolina has been a part of South Carolina ETV and South Carolina Public Radio.

With the generosity of individuals, corporations and foundations, the ETV Endowment is committed to telling authentic stories and is proud to sponsor the World of Cecil.

♪ music ♪ (camera shutters) ♪ ♪ Cecil Williams is a renowned civil rights photographer from Orangeburg, South Carolina.

Williams has spent over 70 years chronicling the events that he says are pivotal to the civil rights movement in this country, events he is determined shall at long last get their just due.

(camera shutters) ♪ jazz music ♪ ♪ >> One of the great events that I covered for Jet magazine was that in 1969, in Charleston, South Carolina, there were many things happening relative to African-Americans not receiving fair pay.

>> Hospital workers in Charleston challenged the inequities of their employer, the local organizers of a union.

And these hospital workers are then joined by the SCLC, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which was founded by Dr. King and I.S.

Leevy and Ella Baker in their late 50s.

<Cecil> So the people of Charleston, South Carolina, marched in the streets of Charleston.

<Dr.

Donaldson> So this small campaign to improve wages and working conditions suddenly becomes a national campaign.

<reporter> How long would you say that the strike in Charleston might continue?

>> Well, it will continue until the local level 99 B is recognized as any other labor union here in South Carolina.

And throughout this free country of ours as a bargaining agent for poor non-professional hospital workers.

<Andrew Young> I think we have demonstrated that the total community supports these strikers and that the support is building, so the longer it stretches out, the stronger we get.

The way that the power structure has used to curtail the aspirations of the poor and especially the Black poor is by threat of police action, violence and jail.

We have helped the people overcome their fear of the police and the National Guard, and now more or less late, it really looks ridiculous for the National Guard to be standing up with bayonets, and here's a bunch of women and children and peace loving men singing hymns and praying.

<officer> Why are they here?

<reporter> Why are they here so close to the church?

<officer> Well, because this is where we had information that the next rally was going to be held and the prior rallies following the march prior to the march down at the medical college involved, thousands of people, and there's been no parade permit requested, and if we're going to have a rally, there's tension.

So we just want to have sufficient people close by to control it so that no one gets hurt, and the only way we can assure that nobody will be hurt is if we have sufficient manpower.

<reporter> Do you think the presence of the Guard might increase brutality?

<officer> No, sir.

(police chat) <Andrew Young> The thing that kept the strike going was the photography.

We couldn't get television to cover most things.

A good photograph of a demonstration, people in action, people in prayer, people in meetings would at least get in Jet.

<Dr.

Donaldson> Those images helped dramatize another key moment.

Many would argue that, that was one of the last major moments of the national civil rights movement because this is where you had some of the most prominent disciples of Dr. King working in concert with local figures.

Fortunately, as that strike evolves in Charleston and there are these powerful images of Coretta Scott King in locked arm with these women marching through the streets of Charleston.

Many of those moments are captured by Cecil Williams.

<Andrew Young>...and I did not know the photographer, but I find out that there was a young man named Cecil Williams who was sending photographs to Jet.

<Cecil> This is after the death of the Reverend Martin Luther King Jet assigned me with a mission and they asked me to cover this event.

Primarily, they were interested in whether or not Mrs. King would then follow in her husband's footsteps.

>> You know, I really... am ashamed to admit it, but I have never had the privilege of going to jail.

I wanted to go, but I back in those years, our children were very young, and he always said that one of us should stay home to take care of the children.

He was concerned that it might be a...traumatic experience for them if they were not old enough to understand the meaning of going to jail, but I must say they understand it very well now.

(applause and laughter) <Andrew Young> After her husband's death, she came because most of the hospital workers were women and they were Black women, and she became a union organizer for Black women in Union 1199 out of New York, and she was not only there sitting in the audience, but she was on the picket line.

She would get up at 5:00 in the morning when the shift changes and she would talk to the hospital workers personally, and she really was a union organizer because that's what her husband gave her his life for.

<Cecil> I also remember that very favorably, because the only cover that I ever made working ten years for Jet was of Mrs. King, first time in my life, achieving the cover of a national publication which contained her image.

♪ A lot of cases, when I went on photo assignments for JET, and sometimes for the NAACP, had I not been there, some of those stories would have gone uncovered.

>> The state legislature passed a law under Governor George Bell Timmerman and the big segregation General Assembly in the spring of 1956, making it illegal to belong to the NAACP and the teachers in Elloree refused to sign the agreement that they would not be members of the NAACP, so they fired them.

<James Felder> Cecil captured that moment of those teachers standing in front of one of the schools in Elloree.

I think it was the elementary school, and that was a moment in time when you saw educators standing together, defying what the authorities want them to do.

<Cecil> At one time, due to the stigma that was attached to it, it was dangerous.

It really belonged to the NAACP, but like these people in Elloree, they'd quit their jobs rather than deny they were members of the NAACP.

<narrator> Undeterred, many did not give up the fight.

Williams captured this telling moment when Orangeburg's Gloria Rackley termination letter in hand walks with her teenage daughter, Lurma.

<Lurma Rackley> The picture evokes the sense of achievement because it was tough.

It was tough for all the people who risked their jobs and their safety and maybe their lives to be involved in the movement at whatever level.

So by risking her job, that meant she was risking her economic stability.

She was risking a lot, but she was brave enough to go ahead and do that, as were a lot of people, to risk everything for for the greater good.

While appealing the injustice of her firing, Rackley, a staunch member of the Orangeburg Freedom Movement, became a field organizer for the NAACP, criss-crossing the state, oftentimes alone and at night.

♪ >>We kind of always knew that Cecil existed in Orangeburg, that he was a photographer, etc.

He was ten years older than I, so we didn't have much friendship at that time, but my first real awareness of Cecil was when he took beautiful pictures, portrait pictures of me at the time of my graduation from high school, and, you know, when you're at that age, I was 16, you want to look beautiful, and the pictures were very nice.

I was very happy with them, and that was my first real, I guess, awareness of Cecil as a photographer.

<Lurma>...and I think I was more aware of him as the chronicler of the Orangeburg movement.

I was 14 at the height of my involvement, even though we were both involved with the movement from 12 and younger, but by the time the teenagers were allowed to go out on the picket line and get arrested and the movement was in full swing, I knew that Cecil was capturing the pictures and that was always important.

We grew up in a family that values history and photos and legacies, and I've always appreciated the fact that Cecil was the keeper of the flame.

<Jamelle Rackley> We are so appreciative, ...of that as a family that he chronicled the movement in Orangeburg and in South Carolina, but also particularly happy that our mother's activities as a civil rights activist at the time that her activities were chronicled.

<Lurma Rackley> So, Mama was on the steering committee of the Orangeburg South Carolina Movement for Justice and Equality, and as a member of the steering committee, she took on a lot of responsibility and took on a lot of visibility, and therefore, along with Reverend Newman and Dr. Charles Thomas and Reverend McCollum and all the luminaries of the movement, Grace Brooks, Mama was among them.

<James Felder> Gloria was a very flamboyant member of the NAACP.

She didn't take no on anything, and she encouraged students to get actively involved, students from Claflin, South Carolina State, and she would drive them all over South Carolina, in her little blue Chevrolet to encourage other people to be a part of the NAACP.

<Lurma> One of the other things that she was most instrumental in overturning was the way Black teachers were treated in the state.

She said, "No, "I'm not going to renounce my membership in the NAACP, "and I don't think any teacher should be required to."

So she lost her job, and when she appealed that firing, the result of the case was that she was reinstated and her demand that Black teachers be given a contract just like white teachers were, would... would be standard.

<Jamelle>...and that no teacher could be fired for being a card carrying member of the NAACP.

That was a part of that lawsuit as well, and which was very significant.

(camera shutters) ♪ <narrator> For Williams, the goal of each photograph was to tell a complete story.

♪ <Cecil> It's one trait that I, I guess, in a way self-taught but also hammered into me by the associate editor of Francis Mitchell of Jet magazine.

Sometimes I would sell a picture to him and it would be maybe something he couldn't use because it did not tell the story, and he would, I can almost remember now him telling me, Cecil, next time you do something like this, we want to see from your picture the who, the why, the what, the where and the when.

We wanted to tell those stories.

We want your pictures to really tell a story like nothing else could.

<Dr.

Twiggs> Cecil wanted to tell what Paul Harvey used to call the rest of the story.

Jet had a lot to do with my being able to really make that a trait... that I would always seek as I taught, as I took photographs.

<Dr.

Millicent> One broader appreciation that we must have for the Cecil Williams of that time or any time is that there's an honesty about photography that cannot be challenged, and so we are grateful for the works of the of the photographers who humanize a lot of what in later days will be subject to misinterpretation.

<Cecil> Coming back into my photography studio now was a different situation.

I tried to capture photographs of people and their faces or their families.

A camera to me is a tool, a tool that has one of the few of this kind that's able to mimic life like no other tool can.

Nowadays, your scrapbook has become your cell phone.

Nowadays, your cell phone takes the place of a photograph being on your mantelpiece, in your home or on a coffee table, and often when you went to a studio, unlike today, where you might take hundreds of pictures of a person with your cell phone or with your regular camera, often times there were only one or two images taken, and so we don't have the appreciation of that magic power to capture in a fraction of a second, a part, a part of that life of a person which mimics life like no other kind of medium that we have available to us.

<Tony Denny> In politics, when...somebody that ran in the other party's primary who has a history in the civil rights movement, says, I want to, I'm a Democrat, but I want to endorse Strom Thurmond, that's a, that's a pretty good news day.

<Cecil> As a child, Strom Thurmond really cast a shadow over my entire life.

He was the governor at one time.

Then he became a United States senator, and so much of what he did seemed to really depict the hatred and the things that were against me as an African-American youth growing up in the South.

in 1985, I decided that I would run against him.

So I launched a campaign to run for the United States Senate, then losing.

I did the same thing in 1995.

<Claudia Brinson> Strom Thurmond was a very big presence in Black and White people's lives in a very negative way for Black people, because he was a segregationist who ran on a segregation platform.

However, he was a complicated person and along the way he became a supporter of Black people's needs through his constituent service.

<Cecil> After losing, my run for the United States Senate, the campaign manager of Senator Strom Thurmond asked me if I would consider helping Strom Thurmond run for reelection.

<Tony Denny> He seemed very open.

He would be honored to sit down and meet with the senator and, you know, talk about what's important to the state and see if there's some common ground.

So, know, I saw it as a real opportunity, right, to win support from a well-known Democrat, somebody whose life had been about documenting you know, the civil rights era.

So it was just fascinating, that he was willing to meet with Senator Thurmond and perhaps support him.

<Cecil> He had very strong opposition coming from Elliot Close, a multimillionaire in the state of South Carolina, and so I thought about it for a while.

I asked whether or not I would be able to take my camera.

They gave me permission to do that.

and so actually, in the 1995 Democratic primary, I really I imagined my entire life where I opposed this person and wanted to take him out of office, but now here I am campaigning for him.

<narrator> It was a move that confounded many Blacks and Whites alike, <Tony Denny> I do very clearly remember that to have Cecil endorse him said a lot beyond just how many votes it might have produced.

The symbolism of it was important.

So it meant a lot to Strom Thurmond.

I know that.

<Cecil> Of the two candidates, I thought that he was still yet be the best of the two candidates.

So this is why I supported him.

♪ >> Cecil's became what he became because of his courage.

A good photographer, has to have the courage to go to the dangerous places where you might get hurt or worse and take the shot.

What Cecil understood, - I learned this years later.

What Cecil Williams understood, somebody has to take the shot and you have to be in the right position to get the shot.

<Dr.

Donaldson> When Mr. Williams is on the grounds of the State House on March 2nd of 1961, there is a shot that he captures of the Statehouse, and when you look at that image, you see two flags on the statehouse at that time.

You see an American flag and you see a South Carolina flag.

Years later, he's back for another event, and I can't recall what the event is, but you see an image of the dome of the statehouse and you see three flags.

You see the South Carolina flag.

You see United States flag and a Confederate flag, and I use those images when I teach and I ask audiences of students what happened.

What happened from the moment Mr. Williams was there in 61 to what happens late in the 60s, and what happens is the movement.

What happens are young men and women in organizations who are even in greater momentum, challenging segregation.

<Rev.

Nelson Rivers III> Cecil Williams photographed many of the most important moments in the history of South Carolina.

The flag came down in 2015, but the impetus was in 2000 at the King Day at the Dome March, when Kweisi Mfume was the NAACP's national president, and Cecil Williams was able to take the photographs of that momentous day.

That was also when the whole state came together.

It was the largest civil rights protest in the history of South Carolina, 50,000 people, and Cecil Williams has photographs from all angles.

He also documents that everything we've ever won in civil rights took a long time.

<Dr.

Donaldson> Mr. Williams chronicles the flag over decades, and so Mr. Williams' images, is almost a portal by which we may see, you know, one of the most controversial debates in state history, the debate about the Confederate flag and whether or not it is a symbol of heritage or a symbol of hate, and so in that long arc of a debate, Cecil Williams has been there on the sidelines chronicling it.

<Rev.

Nelson Rivers III> He took photographs down in Hilton Head when we marched against the flag, and Cecil was the one who recorded it.

He was in Greenville when Jim Clyburn had to wear a bulletproof vest because he was threatened for supporting the removal of the flag.

Cecil recorded all of that.

You will not have a fight unless you keep getting up.

If people can knock you out and knock you down and knock you out, that's not a fight.

That's a knockout.

A fight is when I get back up and keep fighting.

Get back up and keep fighting, but who knows it if Cecil Williams does not record it?

♪ <Luther J. Battiste> Cecil was a frustrated architect.

I think it was his desire probably to go to someplace like Clemson and study architecture, but because of his race, he wasn't able to do it.

<Claudia Brinson> I think Cecil's non-civil rights work or work outside of civil rights activism and photojournalism is important as an instruction as to what one can do when one wants to.

He is truly an inspiration.

When he was told no, he went and taught himself.

<Cecil> Three dimensional blocks like these... helps to formulate design concepts.

These shadows and the blocks that are formed by them helps you come up with very interesting angles.

So this set of blocks, this very set of blocks, helped me to design the present Civil Rights museum.

<Luther> Cecil is a very smart man, very intelligent, and probably self-taught in so many ways, and Cecil always had interesting houses, very modern houses, houses that he designed.

<Cecil> This is the house I designed in about 1975.

It has solar energy features, and it was one of the houses that I really put my heart and soul and mind into.

This house was featured in Ebony magazine, and that made it known all over the country.

So we got telephone calls, correspondence, and it was considered nationally as a house that really moved forward, things that could be done in not only solar energy but house design as well.

I had almost everything that a person could ask for.

In addition to having living quarters, I also had a darkroom, and everything connected to photography that a person could want.

<Luther> The fact that Cecil designed a solar type house does not surprise me because Cecil was a person who was futuristic.

He thought beyond the time and place where he was, was always looking forward, always willing to be innovative and bold, and he was very comfortable doing that.

<Claudia> So when Cecil was interested in something, he figured out how to do it and he did it.

And I find that very interesting about Cecil that he's a person who has so many different skills and so many interests that he can fulfill with the skills that he builds.

<Cecil> All of my life since nine years old, even before picking up a camera, I was attracted by art, but I could not draw as well as I wanted to, and I think the photography in a camera led me to really be more intrigued with what you could do with a camera than just pressing a button.

>> When I came to Claflin, Cecil was just around because I think at the time he was finishing high school, I'm ahead of him and he always came around.

He had a little brownie camera and he took pictures and I became aware of him because he just kind of floated along, He was younger than most of the college students there.

I didn't know that later on we'd become friends.

<Cecil> I guess I'm creative.

I go after goals that really demand a lot of creativity.

I was once interested in becoming an architect after my scribbles on paper weren't very successful and I could find I was able to do them better with a camera, but I was always interested in architecture and I started sketching cars and houses and things like that.

<Rev.

Geoffery Henderson> Cecil Williams, the artist, I picked up on this when I first started working with him.

He would send me somewhere and he says, Okay, let me show you how you get there.

He would not give me directions, would not tell me he would have to draw it out, and he would actually draw the lines, and when you turn on Gervais Street, you make a left on on, on on Huger Street, and then you go here, you see a black and he has to draw the house.

So art is in his blood.

<Dr.

Twiggs> Cecil was in photography, but Cecil was also an artist and I think our friendship came about because we were both taught by Arthur Rose and because we were taught by Arthur Rose.

We kind of spoke the same language.

He knew things that...

I would be saying before I say them, because he knew that I learned what I learned from Arthur Rose, and he learned what he learned from Arthur Rose.

He was a photographer.

And of course, you know, he did dabble in architecture and I think Cecil epitomizes what Rose wanted all of us to do is not to just stay in one medium.

Arthur Rose painted, and he was a sculptor.

Cecil did photographs, does painting, design houses... <Rev.

Henderson> Art is...in him, but then he'll take it to the next level.

He is... has somewhat perfected the painter showcase, which is a combination of art and photography, and he takes all genres of art and put them all together, and I remember we went to a a bridal showcase in Columbia and we had several of his pieces up there, and it amazes me that maybe there were 10 to 15 photographers there, but Cecil was the only one that had artwork there and guys kept coming up saying, "Now, wait a minute.

"Tell me, is this a painting or is it a photograph?

"What is it?"

And we had to answer that question to the professionals all day long.

<Cecil> Making a drawing, an illustration like this is basically the same way that I do a bridal portrait, and sometimes I leave it more photo realistic than other times.

Sometimes I go real abstract with it.

Often I would leave it very photo realistic, especially with brides who might want to be depicted as they really are and maybe enhanced.

<narrator> Building on his early years as a contributor to various news periodicals, Williams soon began publishing his own newspapers and magazines.

<Dr.

Twiggs> Cecil has managed to paint with his lens, and of course, you can do other things too, like you can create brush strokes and he's learned to do that.

So, he's taken photography and taken it to another level, I think.

<narrator> Cecil has used his photographs as fodder for several coffee table books, four chronicled, the Civil Rights Movement, a fifth book, Painter Showcase, worked with photographic art.

Williams is also the subject of a new biography, Injustice in Focus.

Claudia Smith Brinson was tapped as his co-author.

<Claudia> USC Press had been interested in him for quite a while.

So I became sort of a facilitator with USC Press to try to get a book on Cecil's photography, and we decided we needed to tell the story of his life, too, and I was game, and it's just been a wonderful opportunity to get to know Cecil better and to know civil rights history better because he was there, you know, as an eyewitness.

So Cecil is not just a civil rights icon.

I think of him as a means to tell a deep story about what it was like to grow up identified as black and a White dominant one, rather, not rather in a cruel culture, when it came to this.

<narrator> By his count, Williams has amassed hundreds of thousands of photographs, many of those capturing South Carolina's history, succumbing to the ravages of time, were on the verge of their stories being lost.

<Rev.

Henderson> Ever since I have known him, he's come up with these ideas.

So before there was a gimbal, before there was anything else, Cecil invented a shoulder harness for that camera, that Canon L, whatever, and I remember asking, How did you come up with this?

He said it was just a need for it.

<Dr.

Henry Tisdale> I really got to know Cecil and the significance of his work, after returning as president to Claflin University, I realized then that Cecil was a special player in the history of Claflin University because he had the images and he knew the story, so not...

So he could really tell the story in a very special way.

What was surprising to me after getting to know Cecil and the fact that he had thousands and thousands of negatives, that we could lose that history, then it's possible that while we were while we were sleeping and sitting, that those negatives were deteriorating.

Cecil brought that to my attention.

As a matter of fact, I visited his studio and he showed me the files where these negatives were located and he showed me how they were, you know, crumbling because of age and over time and that something had to be done, <Cecil> Starting in photography at nine years old and being a photographer my entire life, I had amassed a tremendous, thousands and thousands, untold thousands of film, and in order to bring those into use today, where I could put them in books and put them in my museum, I had to have a faster way.

<Dr.

Tisdale> Finally, just I just came to the conclusion that we needed Cecil to focus on this, that we didn't need him just to be the photographer of the university, or just the coordinator of the...yearbook.

We needed him to lead this effort to become the leader of historic preservation for Claflin University to preserve the Claflin collection, and of course, at the same time preserve other images that he had as well.

So this is what led to my appointing Cecil as director, as the director of Historic Preservation at Claflin University.

<Cecil> When I got ready to engage in preserving my images for today and for use in a museum, I began experimenting with a project that I called the Film Toaster Project.

<Dr.

Tisdale> The Donnelley Foundation provided a grant for Claflin University to support its digitization project, which included students in a project and the...Getty Foundation, which funded, I think, four historically Black colleges and universities, including Claflin University, their funding also in this digitization project.

<Cecil> The device that you see here is the results of that project.

The film is put into a holder and the holder slides through a film guide, and then the film, of course, is sandwiched between here.

Then you merely move the Film Toaster to the rear and you're able to then capture all of the...film area.

Focus very rapidly on the image that you want to capture and presto, it's done.

The Film Toaster is approximately eight times faster than the scans you could do with... a flatbed scanner.

I have sold Film Toasters around the world making it available to photographers around the world.

This has been a very rewarding thing.

<Dr.

Tisdale> I remember recruiting a student from Atlanta, and the student had a great interest in photography and I was able to recruit this student and say, If you come to Claflin University, I have someone you know, internationally known that you can work with in photography, and his name was Kemet Alston the grandson of Ambassador Andrew Young.

<Andrew Young> Kemet, my grandson not only remembers Cecil Williams, but remembers the messages he taught and shared.

<Dr.

Tisdale> Cecil is one who cares deeply about people, and I think a part of his calling as a photographer and not just as someone who snaps pictures and images and the like, but someone who took a very deep interest in it from a human perspective is a part of what Cecil is all about.

He was not just on the outside snapping the pictures.

He was on the inside, living the movement.

♪ <Jon P. Peede> So I'm chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

It's a wonderful job.

It does take me all across the country and out of the country, and when I was told that he was a finalist for this award, I told my staff, put it on my calendar.

No debate, put it on my calendar, details to follow.

...and so it wasn't a question of being here.

It was...a given from the moment I heard it that I would be here and that, frankly, even if they said, well, you don't have time to speak, then I would be in the audience just to see him get this award ♪ <Dr.

Donaldson> We're fortunate that Cecil Williams is not just a photographer.

He is a historian, he is an archivist.

He's a documentarian, and decades ago, he understood the value and the significance of his photographs.

He understood the research value, the historical value, and for decades now, he has published volumes, But he always knew that there was a larger archive of images.

And so he began to digitize, and he developed his own invention to digitize these images, and so now we have hundreds of thousands of images over six decades of a career.

But Cecil always knew there should be more, and he very much wanted to find a space where these images could be on display for public education, for community engagement and for research.

<Rev.

Henderson> One day he came in like a whirlwind.

He came in as though someone was behind him, and he just came and sat on the edge of my desk and he said, I'm going to turn this building into a museum.

<Cecil> After failing to get the city or the county or the state or anyone else to do it, I started the Civil Rights Museum myself here in Orangeburg.

<Rev.

Henderson> He started, out of pocket, just started to transform one room at a time.

And now we have this large, beautiful museum that's attracting people from all across the country.

It was born in his mind, in his heart, you know, and he want to share it with some other folks.

But they were just not ready to march.

and if you know, Cecil, when he's ready to march, have your boots on.

Let's go.

<Cecil> When people hear about the Cecil Williams Civil Rights Museum, I want them to be excited.

I want them to be excited enough to come and visit.

I want them to be excited enough to really share what history they might have.

Take about an hour and a half and walk around the historical material that I have gathered and hopefully will be chronologically arranged and you'll be able to take a walk back through the last 60 years of our history.

I want this museum to really be a reminder that we will not repeat the negative history.

<Brenda Williams> Orangeburg should have a museum.

There's a lot of history here.

<Cecil> Going back about 30 years, I've been trying to establish a civil rights museum because I believe that it is a period of history that needs to be recorded.

South Carolina was one of the only states in the Deep South that did not have a civil rights museum.

<Brenda Williams> He's made me very proud, doing this, and with his own resources.

<Dr.

Donaldson> He took it upon himself to create the space he always hoped someone else would develop.

<Cecil> Thankfully now, due to museums like mine, I'm hoping that South Carolina's history will forever have an impact on our society and people will be remembered for the sacrifices they have made.

<Cecil> The museum concept and its beginning really was easy for me to do.

36 years ago in the museum site, which was at one time my residence at another time, partially my residence and my studio came about as a result of really having no other place within my means and income to really put it, but it seemed to be very ideal where in the structure, facade and the room 3600 square feet was just really quite adequate.

It was almost as if it was just something laying there waiting to be done, and it seemed to just come all together, building the museum or renovating the museum, I guess, would be a word a better word, was a little challenging.

Thankfully, I had some good assistance, but we did not have to knock walls out, but there was quite a bit of renovation to make it look like a museum to really fill the walls with photographs.

So we started with the floor and just went to the ceiling.

We went to the walls and changed the lighting.

When there were things that were more challenging than my own efforts, then I had to call in electricians and plumbers and so forth, but mostly it's my work that's going into what you see today.

♪ ♪ ♪ <Cecil> I will never run out of historical documentation to place on the walls, and that's usually really a challenge for most museums.

No one told me it would cost millions of dollars to do a museum.

I certainly did not have that to invest, but I have invested what was available to me and I'm almost there with that resource.

The official name of the museum is the Cecil Williams Civil Rights Museum.

Of course, the subtitle is The South Carolina Events That Changed America.

I felt that this reflects the mission of this museum and what we're trying to do to bring South Carolina some of the events that really helped to make this country what it is.

We were involved in many things that are unknown, and most history books don't recall them faithfully.

Most people don't know about them, but we certainly did not want this era and this great period of bravery on the part of South Carolinians to go unrecognized.

<Dr.

Donaldson> We've actually never had a platform or a space that tells that story.

So if you go to Jackson, Mississippi, there is a civil rights museum.

If you go to Montgomery and Birmingham and Selma, there are civil rights museums.

If you go to Washington, D.C., there's a National Afro-American museum.

Well, until recently, we have not had spaces in institutions telling that story, and so now in small town Orangeburg, there is a space in a venue curated by Cecil Williams that tells that story.

And in some respects, that museum is significant because it is now correcting a narrative.

It is now amplifying stories that have been marginalized.

<Loretta Hammond> If you haven't been to C.J's museum in Orangeburg, I pray that you will get the opportunity so that you can recant and see what a struggle lost, stolen or strayed that he has accomplished and found to preserve.

It is really, really story-telling, ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ (camera shutters) <Cecil> We here in South Carolina went from a period of what is called accommodation, which my parents and my grandparents endured in facing rigid segregation, separation of the races by color and tradition, and when that period began to change, motivated by student involvement in many things here in South Carolina, I wanted to really recall these events, and the mission of the museum is not only to display, collect and preserve the memories of these years, but also to reclaim our rightful place in civil rights history.

So much about our history is unknown.

<Dr.

Twiggs> Cecil wanted to tell what Paul Harvey used to call the rest of the story, and so the only way he could do that is to do a museum where he could use his photographs to be his own curator to tell that story, and so I expected this.

I think this is what Cecil arrived at when I say arrived at I mean there are some things that you could go to and some things you can arrive at.

I think Cecil's whole life of moving around taking photos, seeing the world, seeing what happened to Harvey Gantt, seeing all these things, he arrived at a place where he said, now it's time for me to tell the story with the photographs I have.

<Cecil> One of the things that that motivated me to reach this point was that starting this museum was not an overnight thing.

For example, 26 years ago I started on this journey, which has led me to today.

I published a book called Freedom and Justice, because even then I thought that South Carolina's history was largely ignored.

>> It's a simple idea, but no one thought of it.

No one said, Let's do it, and so now that he's he started the Cecil Williams Civil Rights Museum, we're getting a lot of interest from people all around that, you know, want to know how did this come about?

We have other museums across the state, but I don't think anyone else has that kind of hands on a deal with the Civil Rights movement.

<James Felder> Cecil has other objects in that museum that I didn't know he had gathered.

For example, he has Thurgood Marshall's suitcase, the one that he traveled from New York to South Carolina, and all those trips that he came down into in the forties and early fifties.

He has the vehicle that belonged to Reverend J.A.

DeLaine that he had to leave South Carolina in.

He has one of Reverend J.A DeLaine's shotguns.

He has the Bibles of the Briggs family and the Pearson family out of Clarendon County.

Those folks who really put their lives on the line when they signed the petition on the dotted line to start the Briggs versus Elliott case.

So he's been able to collect all of those objects as well.

So when I say nobody in South Carolina, no museum can compare to that from a civil rights standpoint, from a Black history standpoint is Cecil's civil rights museum.

<Rev.

Nelson Rivers III> Cecil has a front row seat to history, and his perspective is unique because he's the only one who sat in his seat.

<Dr.

Donaldson> The other important piece about the Cecil Williams Museum is the Cecil Williams Museum has Cecil Williams so often a photographer's collection sits in an archive.

It may become part of an exhibit, it may become part of a documentary program, but you don't have the photographer chronicling and narrating what has happened, and so what is unique about the Cecil Williams Museum is that young men and women, tourists can come into this space and they can see an image and they can turn to the photographer who can narrate the broader context of that image, and so that is a unique gift that we have that other places can't claim.

♪ <Rev.

Henderson> It is in the forefront.

The museum is most definitely in the forefront of what we do.

Everyone is interested, seems to be interested in the museum.

<Luther> I think it's just amazing what he's done with his Civil rights museum.

It's amazing what he's done to come up with innovative ways to digitize the work that he's done.

That's just Cecil.

It's been who he is the entire time.

A person who who had an eye for the future while capturing the present.

I just think when you look at South Carolinians, Cecil Williams is one of the most remarkable South Carolinians that we produced.

He's a person who was made for that time period.

I just think about what we wouldn't have if he had to capture what he did capture.

<Rev.

Henderson> I think that he pacifies his mind by remembering that there are plans to move the museum to a larger facility downtown.

So I think, you know, even though it's crowded right there then now, you know, he'll say, well, just I'll put up with it.

I'll tolerate it now, because in the short period of time we'll have a little more space, and my fear is that if that doesn't come to pass as quickly as he wants to, you may see bulldozers and equipment out here.

He'll say I'm building another building myself because I can't wait any longer.

♪ <Luther> Cecil is really a renaissance man, but when you had Cecil there capturing that moment, you had an extraordinary person capturing extraordinary events.

<Dr.

Barbara Williams> He's a kind, gentle giant.

He's the type of person that if you can't contribute positively and he would rather you not be a part of whatever it is that he's trying to do.

<Brenda Williams> To have him and have the many organizations that see his value, recognize him, while he's living, really warms my heart.

It makes me very grateful, and I'm very happy that he can experience that.

<Dr.

Twiggs> Cecil's legacy is his struggle to tell the rest of the story.

The story is what civil rights has done for African-Americans, but behind that, the little people, the quiet heroes, students, people who didn't have food on their tables, people who had marched out there.

I believe Cecil legacy is his uplifting of those White heroes.

<Rev.

Nelson Rivers III>Everything we do at one time is present... becomes past.

How do you record the past so that those in the present can benefit from it, photography?

Now video that Cecil has, those photography, those photographs that live and so many ways he is essential to not just to storytelling, but the victories that came from the civil rights movement because it helps people understand it was happening before you got here.

It's happening.

while you're here, and it will happen after you're gone and Cecil did that.

<Dr.

Hine> Cecil has produced the most important body of historical work on civil rights in South Carolina.

Absolutely no question about it.

Now, I'm a historian.

People like Vernon Burton, historian Bobby Donaldson, historians Walter Edgar, historians Millicent Brown, now historians... and there are others, and they've written effectively and sometimes very eloquently about civil rights, and they've provided an important footnotes and scholarship.

Cecil has the photographs.

Photographs grab people's attention when they see a photograph of Fred Moore being expelled from the campus of a president or Governor George Bell Timmerman hanging an effigy, or they see this photograph of the students marching in Orangeburg 1960, or they see the firemen with their hoses out or they see a photograph that Cecil Williams took in Columbia of people marching there in 1963 or his photographs of the hospital worker strike in Charleston in 1969.

Coretta Scott King.

Cecil, I swear missed nothing.

He was everywhere in the state in the fifties and sixties.

He was in Clemson.

He was in Orangeburg.

He was in Columbia.

He was in Charleston.

He was in Clarendon County.

Cecil took hundreds and hundreds, perhaps thousands of photographs over the years that are testimony to what people experience, what people underwent in South Carolina as they protested and demonstrated and sacrificed and tried to make this become a better state.

<Loretta Hammond> Cecil is a photographer that did everything to bring the movement to life and to preserve it.

<Dr.

Donaldson> There have been countless historians who have attempted to tell the story of the civil rights movement in South Carolina, but no one has told that story with the impact and influence has as Cecil Williams.

<Andrew Young> It took a still photographer, with a skilled eye to tell the story without words, and that's basically what Cecil Williams did.

He got in the right place at the right time and he took the right picture.

♪ <Cecil> I think I'd like to be known as an explorer.

You know, come to think of that might just kind of put everything in a nutshell that I'm an explorer of life.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪

SCETV Specials is a local public television program presented by SCETV

Support for this program is provided by The ETV Endowment of South Carolina.