SC Suffragists: The Pollitzer Sisters

Special | 28m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

SC Suffragists: The Pollitzer Sisters.

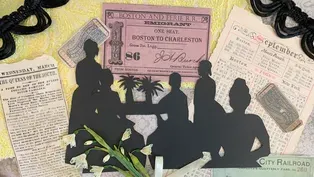

Susan Pringle Frost, Eulalie Salley, Marion Birnie Wilkinson and the Pollitzer Sisters - Mabel, Carrie, and Anita, daughters of a prominent Jewish family from Charleston.

SCETV Specials is a local public television program presented by SCETV

Support for this program is provided by The ETV Endowment of South Carolina.

SC Suffragists: The Pollitzer Sisters

Special | 28m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Susan Pringle Frost, Eulalie Salley, Marion Birnie Wilkinson and the Pollitzer Sisters - Mabel, Carrie, and Anita, daughters of a prominent Jewish family from Charleston.

How to Watch SCETV Specials

SCETV Specials is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

More from This Collection

SC Suffragists: The Rollin Sisters Through 1895

Video has Closed Captions

Sisterhood: South Carolina Suffragists-The Rollin Sisters--Reconstruction Through 1895. (58m 45s)

SC Suffragists: The Grimke Sisters Thru the Civil War

Video has Closed Captions

SC Suffragists: The Grimke Sisters Thru the Civil War. (56m 46s)

Sisterhood: SC Suffragists'-Moving Forward

Video has Closed Captions

Sisterhood: SC Suffragists'-Moving Forward. (56m 49s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipThis program is funded in part by a grant from South Carolina Humanities and the ETV Endowment of South Carolina.

<narrator> At the end of the 19th century with the most hopeful days of Reconstruction well past.

South Carolina was an impoverished, racially divided state.

It's people largely rural, were poorly educated.

And its economy was heavily dependent on one crop, cotton.

Bad health and disease were rampant, especially among the needy.

<Katherine Purcell> Smallpox was ravaging the mills in the upstate.

In Charleston, there were regular outbreaks of yellow fever and typhus because of our water supply.

<narrator> And the rights of women, White and Black, were severely limited.

<Courtney Tollison-Hartness> They could not vote.

They could not serve on juries.

South Carolina was the only state from Reconstruction onward where the right to divorce did not exist.

You could not get a divorce in South Carolina until 1939.

<narrator> Yet, women were among the most ardent reformers at the time, working to bring South Carolina into the modern era.

<Cherisse Jones-Branch> Black women, White women they've been talking about this for quite a long time.

I often tell people, just because you can't cast a ballot, doesn't mean that you aren't politically aware or politically active.

Women have always been having those discussions.

<narrator> At the heart of their story is the fight for the right to vote.

It is a complex history involving gender, class, race, local, state and national politics.

And the very definition of what it means to be a southern lady.

It was a struggle that lasted on and off for decades.

♪ [Sisterhood opening - classical music] ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ [music ends] ♪ The earliest South Carolina women to speak out in favor of suffrage were the Grimke sisters, Sarah and Angelina who were fervent abolitionists and suffragists prior to the Civil War.

In South Carolina, during Reconstruction the Rollin sisters, members of Charleston's aristocratic free Black society greatly influenced the Republican Reconstruction government and chartered the state's first suffrage organization.

By 1880 with the promises of Reconstruction fading and violence against Blacks, a reality, the Rollin sisters left the state and the fight for suffrage seemed forgotten.

Women began to embrace another platform in addition to opposing alcohol, the temperance movement opened the door to focusing on other social issues and afforded women the opportunity to hone their leadership skills.

<Courtney> Women bound together in a national temperance campaign and many women suffrage activists, actually sort of cut their activists teeth as temperance activists firsts.

>> The role of the W.C.T.U.

in the history of the South Carolina women's suffrage movement is really important because it shows us that divide that we saw among women of those who were willing to embrace women's suffrage and those who really shied away with it.

<narrator> As the widow of an alcoholic.

Charleston Sallie Chapin was drawn to the Women's Christian Temperance Union.

After meeting W.C.T.U.

founder Frances Willard at a national temperance convention, Chapin eagerly embraced the cause, quickly becoming a leader in the temperance crusade.

She first established a branch of the W.C.T.U.

in Charleston, then crisscrossed the state, setting up new chapters.

<Joan> Did your community need working education Did it need to pass child labor laws?

What else was it that you needed to work on within your community?

<narrator> Charged with recruiting southern women, both White and Black.

Chapin called herself an unreconstructed rebel.

Clad in all Black, she charmed her audiences with folksy stories and stressed social issues such as education and child labor laws rather than the right to vote.

<Joan> She is very proud of her Confederate history and role of her family in the confederacy and what that meant in part was that she was really reluctant to embrace women's suffrage, because she saw that as too radical for southern women, not proper for southern women like herself.

<narrator> Enter Virginia Durant Young of Fairfax, South Carolina.

Young was both a member of the W.C.T.U.

and a suffragist.

Virginia's career as a reformer began with writing magazine articles and newspaper columns.

As editor of the Fairfax enterprise, she was able to draw attention to the movement and she began to advocate for suffrage and to organize.

By 1890, she was the dominant figure in South Carolina's efforts to revive the fight for the female vote.

But this time, the fight favored White women only.

<Joan> She is bringing South Carolina into the national movement and she brings some of the national figures from the NAWSA, which is the National American Women's Suffrage Association to South Carolina to speak.

<narrator> Young founded the South Carolina Equal Rights Association, the S.C.E.R.A.

in 1890.

It became affiliated with the National American Women's Suffrage Association known as NAWSA.

Nationally, the White General Federation of Women's Clubs was founded in the same year and women's clubs although segregated into Black and White clubs began to spring up across the country.

>> You really begin to see the development of the movement for Black or White women really coming to a head in the late 19th and early 20th century.. You begin to see the formation of these national organizations and then your state affiliated organizations and your local organizations.

So what they do in 1896 essentially is that they form a national organization out of clubs that have long existed.

We see the National Association of Colored Women being founded in 1896.

>> While everybody thought they were sitting drinking tea and a little sherry, they were transforming the education system, transforming the health system in South Carolina.

the Black women's groups, they were rescuing children from horrific situations.

These women, they did a lot of work.

<Cherisse> Many of their objectives are similar.

They're concerned about home, they're concerned about the family.

They're concerned about politics.

But there's always that racial divide that keeps them from working together as effectively as they might, at least organizationally.

<narrator> While the struggle for women's suffrage was slowly evolving in the south, southern states brutally challenged Black men's rights to the ballot by using violence and intimidation and by rewriting their state constitutions to favor White supremacy.

At the 1895 South Carolina Constitutional Convention, suffragists led by Virginia Durant Young championed the inclusion of women's suffrage for White women only.

They argued that the same tactics used to eliminate Black men from voting could be used for Black women, as well.

Their approach drew the support of suffragists at the national level.

By design, the new 1895 South Carolina constitution disenfranchised many African American men.

Among other restrictions, it imposed literacy tests that could be waived only if the voter owned property valued at 300 dollars or more.

But the argument for a women's suffrage amendment even as a strategy for upholding White supremacy failed.

<Valinda Littlefield> The males are in control of politics.

And they really aren't interested in women having the right to vote because they see women as - "Home is here.

That's where you should stay."

Politics has never been a space that women, White women should be involved in.

<narrator> Once again, the suffrage movement in South Carolina subsided, but the women's club movement, Black and White continued to move forward.

<Katherine> South Carolina presents a very interesting conglomeration of women's clubs that inevitably fed into the National Women's Suffrage Movement by promoting education and uplifting children working separately for the same end.

<Joan> Of course they have different motivation and reasons for doing so and they're facing a slew of different kinds of problems.

<narrator> In 1898, White women in South Carolina formed the South Carolina Federation of Women's Clubs led by Charlestonian Louisa Poppenheim.

Louisa and her older sister, Mary were very active in the women's club movement.

Louisa as the president of the South Carolina Federation of Women's Clubs and Mary as the President General of the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

Beginning in 1899 and for about 14 years, the Poppenheim sisters published a monthly magazine called the Keystone.

It was the official organ for both, women's clubs and U.D.C chapters around the south, thus pointing up the manner in which the lost cause movement, which celebrated the confederacy suffused White middle and upper class society.

<Cherisse> Black women understand that because of the climate in which they're operating with intense racism, Jim crow segregation, if you're in the south and in truth, in the north and the west, they understand that they've got particular issues in this moment to speak to that impact Black women or Black people rather, no matter where they are in the country.

<Valinda> This is a movement by mainly middle class women, both Black and White and the club movement runs parallel.

You have the Black Club women's movement and you have a White club women's movement.

Out of this particular movement, you get off shoots that might deal with suffrage.

<Joan> It's not just that they're thinking about it as women wanting to be equal with men and therefore getting the right to vote, it's really about how do you advance the whole community.

<narrator> Marion Birnie Wilkinson became the most important Black club woman in the state.

Originally from a wealthy Charleston family, by 1899 she was leading the Black branch of the W.C.T.U.

in Charleston, when her husband Robert Shaw Wilkinson became president of South Carolina State College, they moved to Orangeburg and she expanded her leadership there.

<Joan> Marion Wilkinson founds the South Carolina Federation of Colored Women's Clubs in 1909.

This becomes a really important organization in the state.

<narrator> Wilkinson was active in the National Association of Colored Women and very involved in a network of Black professional women who led reform efforts in cities across the country.

Locally, she started the Sunlight Club.

Their emphasis was on education both for themselves and for the community.

With the beginning of the 20th century, the national movement for women's suffrage surged ahead.

On March 3rd 1913, the day before Woodrow Wilson's first inauguration as president, thousands of women marched along the inaugural route in a massive parade in Washington DC.

The parade brought new inspiration and attention to the call for a constitutional amendment guaranteeing women the right to vote.

A new generation of South Carolina women across the state began to advocate for the vote.

The first club explicitly formed to champion women's rights was the New Era Club, organized in Spartanburg in 1912.

<Courtney> The New Era Club was a club that supported women's issues, children's issues, community issues.

One of their first actions however, was to wire President-Elect Wilson to express her support of women's suffrage and to encourage his support of women's suffrage.

In 1914, they decided to rename themselves the South Carolina Equal Suffrage League.

They inspired leagues in Charleston and then in Columbia and over the next several years throughout the state.

By 1917, there were over 25 local South Carolina equal suffrage leagues across the state with a membership totaling 3,000.

<narrator> Momentum for the women's vote was building in the Palmetto State and it got a boost from a scandal after an unprecedented custody battle between two legendary South Carolina political families in 1909.

The financially independent granddaughter of a prominent South Carolina politician, Lucy Pickens Dugas was married to Benjamin Ryan Tillman the Third, the son of the infamous South Carolina politician and White supremacist, Pitchfork Ben Tillman.

They had two daughters Douschka and Sarah.

<Valinda> Ben for all practical purposes is a drunkard.

He gambles and Lucy leaves him and takes their children with her.

<narrator> While living in DC with the children, Lucy fell ill and was confined to bed.

Tillman took the girls allegedly to visit his mother, but actually left them in his parents care.

His father was serving in the US Senate at the time.

Tillman's mother, Sally Tillman then took the children to South Carolina.

<Valinda> At that time, a husband could deed his children to somebody else, not the wife, but the husband could.

And because he was a drunkard, he knew that no judge would give him custody of these kids, so, his dad and mom being upstanding citizens, he was on safe ground, and that's what he did.

<narrator> Lucy received a letter from the Tillmans' attorney J.W.

Thurmond, father of future South Carolina Senator J. Strom Thurmond.

The letter stated that her husband's actions were legal, based on a South Carolina state law and would remain in effect until her daughters turned 21.

<Valinda> Well, Lucy has other ideas and she has the money to fight this.

And so she does.

And it goes to the South Carolina Supreme Court.

<narrator> The case caught the attention of the local and national press.

Women from across South Carolina wrote to The State newspaper, denouncing Ben Tillman.

They traveled to Columbia to observe the trial.

So many women came, that the first day of the proceedings was delayed for lack of seating.

<Valinda> So, in 1910, it is a unanimous decision that Lucy gets her children back.

But what that did, was to open the eyes of many other women, like Eulalie Salley.

<narrator> Eulalie Chafee Salley grew up in a well to do family in Aiken, South Carolina.

She was married, to the mayor of Aiken, had two children and seemed destined for the quiet life of a proper southern lady, that is until the Tillman scandal awoke the suffragist within.

In 1910 she joined the Equal Suffrage League paying the membership fee of one dollar and declaring it the best dollar she ever spent.

<Courtney> She spent most of her time advocating for women's suffrage.

She was extraordinarily passionate about this cause.

When her husband was somewhat reluctant to support it, she developed her own wealth and used her own funds for this cause.

<Valinda> She also drops pamphlets out of an airplane, enters a boxing tournament to earn money for the suffrage movement.

She is probably... one of the some would say, the most... flamboyant suffragists South Carolina produced.

<narrator> The early 20th century was known as the progressive era.

And a trio of sisters in Charleston embraced the opportunities for social reform.

The Pollitzer siblings, Carrie, Mabel, Anita and their brother Richard came from a prominent and influential Jewish family.

Their parents, Gustave and Clara Pollitzer were active members of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim, the birth place of Reform Judaism in America.

The three Pollitzer daughters reflected their father's civic engagement taking active roles in reform movements at the local and national levels.

<Katherine> At this time, the Jewish community was not supporting suffrage and the Pollitzer sisters were not adverse to writing letters to rabbis, quoting sacred text and reminding the Jewish leaders that in tradition, both men and women were equal in leadership.

All three sisters went up to teachers' college, Columbia University in Manhattan, lived with family and moved about the art circles and the political circles within the Jewish community.

And that's where they gained momentum with their suffrage movement in Charleston.

Carrie Pollitzer is the eldest of the Pollitzer children.

She is known for bringing free kindergarten to Charleston.

She was the very first person to bring school lunches to South Carolina.

Carrie is also known for setting up women's suffrage booths on Broad Street and King, handing out suffrage pamphlets and trying to talk Charlestonians into looking outward rather than looking inward.

<narrator> Carrie Pulitzer also worked for the admittance of women to the college of Charleston.

Told that there were no facilities for women on campus, she said about raising the necessary funds to provide said facilities and within a year, female admittance was granted.

Mabel, the second of the sisters helped found Charleston's first public library and taught biology at Memminger High School for over 40 years.

<Katherine> She developed probably the very first sex ed program in the country.

She had all of these young women coming to her asking questions that their mothers would not answer.

And she would query these students saying, "You're wearing an engagement ring.

"Would you choose the first refrigerator you saw?"

<narrator> Anita was the youngest of the Pollitzers.

Like her sisters, she attended Columbia University in New York City where she studied art.

In New York, she joined the Art Students League and befriended Georgia O'Keefe, who at the time was an unknown artist, but who shared the views of the suffragist movement.

Although she spent most of her life outside Charleston, Anita became arguably South Carolina's most well known suffragists.

While all of the Pollitzer sisters were influential in the struggle for women's rights, they followed the lead of a woman named Susan Pringle Frost.

Frost was the founder of the Charleston Equal Suffrage League and the Pollitzer sisters were charter members with Carrie serving as secretary and membership chair.

<Katherine> While, Carrie and Mabel stayed at home working on the Charleston front, Anita was worried that suffrage would become a state's matter.

And so she wanted to push to make it a national issue.

<narrator> Anita went to work with the National American Woman Suffrage Association through which she met Alice Paul, who would become her good friend and one of the most prominent American suffragists.

Paul had spent time in England where she was influenced by the more radical British activists.

<Courtney> They would throw water on members of Parliament.

They would sometimes attack them physically.

One suffragette in England threw herself in front of King George the fifth's horse, ultimately dying as a result of that action.

<narrator> Alice Paul was herself arrested and sent to prison in England, multiple times.

The experience radicalized her.

<Katherine> She learned how to get the attention of politicians and when she returned to the United States, began using these tactics.

That did not sit well with many of the suffrage movement.

Especially those from South Carolina.

<Courtney> She broke off from NAWSA and established the congressional union, which was soon renamed the National Woman's Party.

>> Although South Carolina was not one of the major players in the suffrage movement and did tend to be much more conservative when it came to women's gender roles, in fact, they had a group that was very involved in the more militant branch of the movement, which is a little bit unexpected.

<narrator> In 1917, the National Women's Party began picketing the White House.

Called the Silent Sentinels, they stood through every kind of weather, holding signs criticizing President Woodrow Wilson for ignoring women's suffrage.

This was during World War I and the women were chastised for putting women's rights before the war effort.

<Katherine> The women were arrested.

Some of these women were imprisoned.

Some of these women were sent to work at camps.

Many of the women who were imprisoned went on hunger strikes and had to be forced fed.

<narrator> Ultimately, 168 women were imprisoned, but the suffragists were undeterred.

And the protests continued.

In February 1919, the woman suffrage amendment was defeated by just one vote in the Senate.

Fearing that it would die before the end of the congressional session, in March of that year the N.W.P.

organized a cross country train tour to highlight their cause and to pressure legislators.

Anita Pollitzer made sure that train would stop in South Carolina.

Indeed, Charleston was its first destination.

The suffragists' persistence and reports of their horrific treatment in prison, which was well documented in the press, began to change public opinion.

<Joan> They were horrified by the treatment of those women while they were imprisoned and kind of felt like even though these women probably shouldn't have been picketing the White House to begin with, it was not proper to imprison women and treat them so poorly.

<narrator> President Woodrow Wilson switched his position and then endorsed the vote for women.

And on May 21, 1919, the House of Representatives passed the 19th amendment known as the Susan B. Anthony amendment.

Two weeks later, the Senate followed and the N.W.P.

began campaigning for state ratification.

In August 1920, Anita Pollitzer was deployed to Nashville, Tennessee.

35 of the necessary 36 states had ratified the amendment.

Only Tennessee remained in a position to vote on ratification that year.

A young legislator named Harry Burn was set to cast the deciding vote.

<Katherine> Harry Burns says that his mother sent him a note, pleading that he cast his vote for the 19th amendment.

We know that Anita spent quite a bit of time with Mr. Burns.

I think Anita had convinced him to cast that vote needed for the 19th amendment.

<narrator> First introduced in Congress in 1878, the 19th amendment to the Constitution of the United States ensuring that the right to vote could not be denied on the basis of sex was ratified on August 18th, 1920.

[" Ain't she sweet" by Gene Austin] ♪ Ain't she sweet, See her coming down the street.

♪ ♪ Now, I ask you very confidentially, ♪ ♪ Ain't she sweet?

♪ ♪ I repeat, don't you think that's kinda neat?

♪ ♪ And I ask you very confidentially.

♪ ♪ Aint she sweet?

♪ ♪ Yes, sir.

That's my baby.

No sir.

- ♪ <narrator> It was not until 1969 that the Palmetto State finally ratified the 19th amendment.

86 year old Eulalie Salley was there for that momentous occasion, standing directly behind Governor Robert E McNair as he signed the bill, she remarked, "Boys, I've been waiting 50 years "to tell you what I think of you."

This program is funded in part by a grant from South Carolina Humanities and the ETV Endowment of South Carolina.

SCETV Specials is a local public television program presented by SCETV

Support for this program is provided by The ETV Endowment of South Carolina.