The Big Burn

Season 27 Episode 4 | 52m 12sVideo has Audio Description

In the summer of 1910, the largest fire in American history raged in the Northern Rockies.

In the summer of 1910, hundreds of wildfires raged across the Northern Rockies. By the time it was all over, more than three million acres had burned and at least 78 firefighters were dead. It was the largest fire in American history.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

For Season 27 of American Experience, exclusive corporate funding is provided by Liberty Mutual Insurance, major funding by The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, funding from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting...

The Big Burn

Season 27 Episode 4 | 52m 12sVideo has Audio Description

In the summer of 1910, hundreds of wildfires raged across the Northern Rockies. By the time it was all over, more than three million acres had burned and at least 78 firefighters were dead. It was the largest fire in American history.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch American Experience

American Experience is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

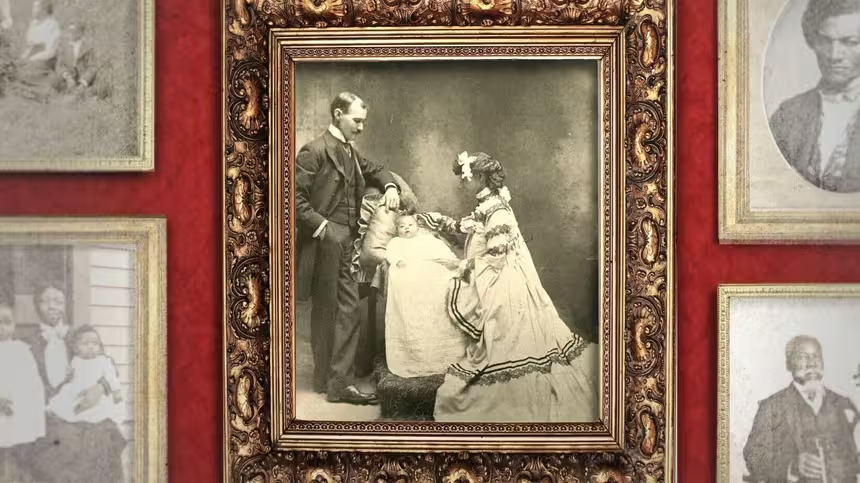

When is a photo an act of resistance?

For families that just decades earlier were torn apart by chattel slavery, being photographed together was proof of their resilience.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMore from This Collection

Since pre-colonial times, Americans' relationship to the natural world has shaped politics, policy, commerce, entertainment and culture. In this collection, delve into our complicated history with the environment through American Experience films exploring wide-ranging topics, from our struggles to exert dominion over nature to our attempts to understand and protect it.

Clearing the Air: The War on Smog

Video has Audio Description

The story of L.A.’s noxious smog problem and the creation of the EPA and Clean Air Act. (52m 39s)

Poisoned Ground: The Tragedy at Love Canal

Video has Audio Description

The story of housewives who led a grassroots movement to galvanize the Superfund Bill. (1h 52m 30s)

Video has Audio Description

Unsung scientist Mária Telkes dedicated her career to harnessing the power of the sun. (52m 22s)

Video has Audio Description

The woman whose groundbreaking books revolutionized our relationship to the natural world. (1h 53m 15s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ ♪ (horse nickers) ♪ ♪ (horse whinnies) ♪ ♪ NARRATOR: On August 19, 1910, an assistant forest ranger named Ed Pulaski rode out of the smoke-filled Bitterroot Mountains that loomed over the town of Wallace, Idaho.

For months he and his crew had been fighting wildfires in the Bitterroots, but despite all of their efforts, he was afraid the town was going to burn.

TIMOTHY EGAN: Ed Pulaski comes down and sees his wife and sees his adopted daughter, Elsie, and says, "Leave.

"You've got to get out.

You've got to leave to save your life."

She says, "No, I'm going to stay here."

And so he tells her to go up and hide in this reservoir.

If it really gets bad, they can go in the water.

So, the next day they go out to the edge of the trail there, kiss and say goodbye and thinking it'll be the last time they'll see each other.

NARRATOR: That afternoon, without warning, the wind began to blow, and flaming embers shot down from the sky, igniting buildings.

Within minutes, Wallace was ablaze.

(people clamoring) Desperate residents tried to salvage their belongings.

Women and children were loaded onto the last train out of town.

The roar of the wind and flames was overwhelming, the air so hot it was hard to breathe.

The biggest wildfire to ever hit the Northern Rockies had begun.

♪ ♪ (fire raging) EGAN: The Big Burn destroys an area the size of Connecticut in 36 hours.

We've never had anything close to it.

NARRATOR: It was an inferno that not only transformed the landscape of the West, but forever changed the nation's attitudes about its public lands.

STEVE PYNE: The Great Fires in the Northern Rockies hit the U.S. Forest Service in ways that rippled through society.

The Army call-out, the political fights over strategy...

It's all slammed together in one giant package.

That made them great.

NARRATOR: It was a story of arrogance and pride, a belief that nature could be managed and fire brought under control.

MICHAEL KODAS: There was an attitude that if there's something wrong in the forest, we can go in there and fix it.

It was almost as if wildfire was this beast that we can actually hunt down and eradicate.

NARRATOR: The selfless courage of a small group of men would inspire the nation, but questions would linger about whether their sacrifice had all been in vain.

PYNE: We can celebrate them as people of their time and era who played out fully the roles that the culture ascribed to them and yet admit that it would have been better if we'd done something else.

It's a time of catastrophe, a time of change, a time of coming up with a new vision.

If you look at the landscape, the scars of 1910 are still there.

♪ ♪ (dog barking) NARRATOR: In the flea-bitten collection of ramshackle buildings known as Taft, Montana, college graduates were about as rare as an honest poker game.

So the locals took notice when, in the early spring of 1907, a group of fresh-faced rangers from the United States Forest Service stepped off the train.

The recent arrivals had come to manage some of the newly created national reserves in the West, but nothing had prepared them for a place like Taft-- (gunshot echoes, woman screams) a boisterous, brawling row of gambling parlors, whorehouses, and saloons.

One reporter called it "the wickedest city in America."

(glass shatters) PYNE: You've got these temporary communities, particularly along the railroad.

Lots of loose women, lots of loose men, lots of bums, people under assumed names.

There's just this whole throng out there.

How do you impose some kind of order on this process, which had been characterized by almost complete chaos?

EGAN: Taft had a higher murder rate than Chicago and five prostitutes for every man, they said, and when the rangers showed up, they were horrified.

They cabled back to Forest Service headquarters, saying, "Two undesirable prostitutes setting up business on Forest Service land.

What should we do?"

And someone cabled back, "Get two desirable ones."

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: The newly minted rangers had been sent west by the founder of the Forest Service, an aloof, hard-driving bureaucrat with an almost missionary zeal for the management of America's public domain.

In less than a decade, Gifford Pinchot had parlayed his family's wealth and social connections, a passionate love of trees, and a deft hand at politics to become America's preeminent forester.

EGAN: Pinchot is one of the most fascinating characters, not just in American conservation, but in American history.

He was a patrician.

He was a very odd duck.

He preferred to sleep on rocks than a soft bed.

He was an ascetic.

But he had a vision.

Even though he was the product of a family that made their money in clear-cutting forests, he became, you know, one of the founding figures of saving forests.

♪ ♪ CHAR MILLER: For Pinchot, nature was really a place of respite.

It's where you went to just forget other things and become whole and become safe and in that process come to know yourself.

NARRATOR: Pinchot had forged friendships with some influential men in the growing conservation movement, in particular the famous naturalist John Muir.

"You are choosing the right way into the woods," Muir told the young man.

"You will never regret a single day spent thus."

Pinchot also developed a rapport with the young governor of New York, Theodore Roosevelt, a bond strengthened by their love of the wildness of nature and a boyish thrill at testing themselves against it.

When Roosevelt ascended to the White House in 1901, he brought Pinchot into the inner circle of his administration.

The two men were determined to seize the mantle of conservation and radically rethink how the nation managed its estate.

(loud thud) Up until the late 19th century, the country had done its best to develop its open spaces-- encouraging the wholesale harvesting of timber, industrial mining on a vast scale, the blasting of railroads through the mountains and across the continent.

ALFRED RUNTE: For over a century, their country has given its land away and Theodore Roosevelt and Gifford Pinchot are calling a halt to that.

They're basically saying, "We're going to change the way we look at the future."

NARRATOR: Roosevelt and Pinchot were worried that unless they acted quickly to protect America's last great stands of white pine, spruce, and fir, the forces of unbridled capitalism would devour them once and for all.

PYNE: Timber was really a critical industrial product and we were going to run out, much like an oil crisis in present times.

So the solution was to regulate this unsettled land as a public domain that would then be governed by scientific informed bureaus, and this would allow us to conserve it, not lock it up, but to use it in some kind of rational, regulated way.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Their progressive vision imagined a new kind of commonwealth-- national forests, controlled by an enlightened corps of rangers, overseeing not just the timber, but also the minerals, the water and the wildlife for the benefit of all Americans.

A national forest is not a pristine sanctuary, it is a utilized landscape.

So, it's a different model than a national park.

You can hunt on it, you can graze on it, you can mine on it.

Its purpose is to be managed.

NARRATOR: Previous presidents had already set aside large swaths of public land, but Roosevelt went much further, radically expanding America's national forests.

Then, in 1905, he placed them under the control of the Bureau of Forestry, now called the U.S. Forest Service, with Pinchot in charge.

EGAN: At one point, Roosevelt and Pinchot are on the floor of the White House, maps spread out all over, and they are mapping out future United States forests, and Roosevelt says, "Oh, God, have you ever been up in the Flathead Valley?

I had a bully time there once."

He goes, "We've got to include that."

♪ ♪ In Roosevelt and Pinchot's time, they tripled the acreage of the national forests.

So you have 200 million acres under the range of the Forest Service, bigger than most European countries.

NARRATOR: Now, the idealistic group of young men that constituted Pinchot's Forest Service were given the task of bringing their new conservationist vision to some of the wildest parts of the American West.

One of Pinchot's first hires was William Greeley, the hard-working son of a Congregational minister from Upstate New York, who had spent a summer in the saddle alongside Pinchot, marking some of the first surveys of the new national forests.

"We were privileged to become Pinchot's rangers," Greeley remembered.

"We had the thrill of building Utopia and were a bit starry-eyed over it."

Pinchot returned the sentiment.

He asked the 29-year-old Greeley to oversee nearly 30 million acres, covering most of Montana, Idaho, and parts of South Dakota.

Each of the 160 rangers under Greeley would be responsible for almost 300 square miles of national forest.

♪ ♪ MILLER: Pinchot gave them a mission.

He gave them a sense of calling, a sense that the world could be changed through their own work and then let them go out to the West and work on these extraordinary landscapes.

EGAN: They called what they were doing "The Great Crusade."

In some ways, it was a religious crusade to them.

They were doing God's work to preserve the earth.

NARRATOR: Pinchot was known as "The Chief," or "GP," and the rangers so admired his leadership that they welcomed the nickname "Little GPs."

"He made us feel like soldiers in a patriotic cause," one of his first students remembered.

CHARLES WILLIAMS: Pinchot expected the GPs to go out and practice forestry the way they'd been taught, full of innovation, energy, and they were up for the job.

But what made their job difficult were the people that they encountered in these towns-- the roustabouts, workers in the timber industry, in the mines and railroads.

EGAN: It was a great, great culture clash.

Forest rangers were not popular at all.

They were considered outsiders.

Even though this was public land, people still felt they could do as they wanted to with it.

RUNTE: The rangers are in charge of people who do not want the Forest Service to be there.

Because the ranger is indeed standing between the frontier mentality and the resource, standing between what the frontier wants for the moment and what Gifford Pinchot believes the country needs for the future.

NARRATOR: As they squared off to do battle over national forests, both sides would be humbled by one implacable foe-- nature itself.

(fire crackling) ♪ ♪ EGAN: Fire is the last wild element of the West that hasn't been controlled.

Every wolf is gone.

They've exterminated the grizzly bear.

They're all gone.

So what's left is fire.

And it's important to understand how fire is perceived at the time.

The public, they fear it because these are wooden towns going up at every railroad stop all over the West.

They really fear it.

(timber crashing) RUNTE: There were a lot of steam locomotives in the West and they were passing through these timbered areas causing forest fires.

EGAN: When they come through, sparks go off.

And the railroads aren't putting out these fires.

They go to the Forest Service and say, "Well it's your land, we're only coming through.

You've got to put these things out."

♪ ♪ PYNE: You don't have roads, you don't have trails.

It may take you a couple days to even find a fire.

I mean the thought that these rangers could even begin to cope with this, it just staggers the imagination.

What were they thinking of?

♪ ♪ EGAN: Fire fighting was a very, very primitive science.

They were learning as they went along.

MICHAEL KODAS: The only way to fight fires in 1910 was with hand tools.

You basically were in there with an axe or a hoe or a rake or, you know, whatever you could get your hands on.

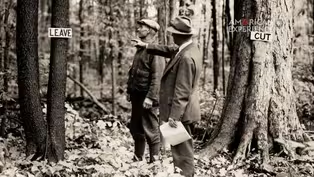

PYNE: You were building what we would call a fire line now.

You're cutting a path, clearing it of all debris.

Some parts, say three or four feet would be completely down to mineral soil so no fire could cross.

♪ ♪ This is just brutal grunt labor.

You're just digging, chopping, scraping and moving on.

♪ ♪ (birds chirping) NARRATION: As primitive as fire fighting was at the turn of the century, Gifford Pinchot believed it was an essential part of his new department's mission.

Fire threatened the nation's timber, the very resource he and his rangers existed to protect, and they had to extinguish it at all costs.

♪ ♪ But Pinchot had another reason to embrace a war against fire.

He saw in it the key to his organization's survival.

Ever since the creation of the Forest Service, timber and mining barons-- many of whom also had seats in Congress-- had attempted to slash the agency's staff and budget at every turn, determined to starve it out of existence.

Pinchot needed a weapon to fight back.

RUNTE: Gifford Pinchot understands how dramatic fire is.

If you have something dramatic, then you can find a reason for the U.S. Forest Service to exist.

Pinchot argues, well, "Who's going to protect these lands if we don't?

"The railroads aren't protecting them.

We have to protect them."

PYNE: Pinchot is very smart, perceptive, well educated, but he was also deeply political and he knew that fire was the most graphic and simplest way to convey the message about forest destruction and the need for some kind of organized protection.

NARRATOR: In speeches, articles, and testimony in front of Congress, Pinchot made his case in starkly moral terms.

"The question of forest fires, like the question of slavery, "may be shelved for a time, at enormous cost in the end, but sooner or later, it must be faced."

EGAN: He stakes everything on the idea that we can control fire.

Though they'd never fought a fire before.

That's what's so interesting.

The Forest Service is only five years old in 1910.

They have never fought a big fire.

And it's almost like he's asking for it.

It's almost like hubris-- "Nature, bring it on."

♪ ♪ (insects chirping) NARRATOR: By the early summer of 1910, Bill Greeley was sleepless with worry.

From his headquarters in Missoula, he was monitoring the millions of acres under his control, and everywhere the news was bad.

1908 had been a very dry year, and 1909 worse still, but nothing could have prepared the Forest Service for the drought that befell the Northern Rockies in 1910.

EGAN: It's a dry summer.

It had been a wet, snowy spring, but then, a switch went off in May and it did not rain.

All of May, no rain.

All of June, no rain.

All of July, no rain.

The forest is tinder dry.

You walk over the thing, it's like potato chips crinkling walking on the ground.

NARRATOR: In a cable to his men, Greeley implored them to "strengthen the patrol and retain a strong guard."

The humidity, he warned, "had dropped to the level of the Mojave Desert."

♪ ♪ For many of the new rangers, fresh from their elite universities, the drought-stricken terrain of Montana and Idaho felt like an alien world.

Not so for Ed Pulaski.

He was two decades older than most of the others, having roamed the West since he was 16, working as a master carpenter and blacksmith, a plumber, millworker and steamfitter, mining for copper in Montana and silver in Idaho.

He'd kicked around all over, he's middle aged, he's sort of washed up, but he's a man of all trades.

He's a man of the people, too.

He, you know, really relates to folks.

He's done everything that a Western man will do at that time.

NARRATOR: Although he lacked a formal education from back east, Pulaski had mastered the curriculum of the forest.

He knew the mountains in his bones, and he knew how to survive in the wilderness.

He was a man of few words, but when he spoke, the locals learned to listen.

PYNE: In 1908, Pulaski joined the Forest Service and became the ranger at Wallace.

He was on his second marriage with Emma.

They adopted a daughter named Elsie, who was seven or eight at the time.

So, he's a settled guy, he's got a house in town and he's responsible for what happens in the field.

(thunder booms) NARRATOR: Late in the evening of July 26, 1910, Ed Pulaski awoke to hear the heavens unleash a deafening, almost continuous volley of thunder.

It was what he had feared most, a violent electrical storm, bolt after bolt of lightning and no rain.

By the next morning, nearly 1,000 fires were burning across 22 national forests in the Northern Rockies.

The blazes threatened the string of railroad towns that extended westward from Missoula, ending with the miserable collection of tents and tarpaper shacks that constituted Taft.

On the Idaho side of the Bitterroots, along the southern spur of the railroad, the hardscrabble hamlet of Avery looked vulnerable, as did Wallace, the biggest town in the region, to the north.

With only 160 rangers in the field, the biggest test of the new Forest Service was at hand, but as the Little GPs rushed to marshal their forces, they did so without the help of their founder and leader.

Gifford Pinchot had been fired.

♪ ♪ The Forest Service chief had clashed repeatedly with Theodore Roosevelt's successor, William Howard Taft, convinced that the new president lacked the appropriate commitment to the conservationist crusade.

Finally, their quarrels became so contentious and so public that Taft had no choice but to force Pinchot to step aside.

The day after his dismissal, Pinchot had arrived at the agency's office in Washington to find his organization in shock.

Trying to rally the faithful, he proclaimed, "You are engaged in a piece of work that lies "at the foundation of the new patriotism of conservation.

"Don't let the spirit of the service decline one-half inch.

Stay in the service, stick to the work."

He was greeted with a thunderous ovation.

Back in the Northern Rockies, however, the rangers urgently needed men on the ground.

But men willing to fight fires were in short supply.

MacLEAN: In the summer of 1910, you had a Forest Service that only had fewer than 500 rangers nationwide, but they knew that they were going to get in a lot of trouble that summer, and so they opened the coffers and they said, "Go out and hire everybody you can find."

♪ ♪ EGAN: The forest rangers assembled an army of men, most of them immigrants.

They paid them 25 cents an hour, and the immigrants came from all over.

They are putting out the call.

"We're going to fight this thing.

We are going to attack these hundreds of fires."

It's 100 degrees, it's dry, it's dusty.

It's on really tough vertical terrain.

A lot of people suffered injuries, they quit, they mutinied.

At one point they literally said, "Men, men, men."

They opened the jails of Missoula, Montana.

They let felons out, convicted murderers, some guys who had their handcuffs on when they were sent out to the front lines.

So, any male with a pulse was thrown against this fire.

NARRATOR: By early August, Bill Greeley had managed to assemble as many as 4,000 men on the fire lines, but with new blazes breaking out all the time, the local labor pool was quickly exhausted, and a call went out to Washington for help.

President Taft at first resisted the idea of committing federal resources to the West, but the situation in the Rockies became so dire and the press criticism of his dithering so unrelenting, that on August 7 he finally decided to act.

WILLIAMS: Taft realized that if he didn't do something, he was going to get blamed for a huge loss of life, not to mention property.

So he authorized the secretary of war to put the Army in.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Taft sent a total of 4,000 troops to the Rockies, including seven companies from the 25th Infantry, known as the Buffalo Soldiers.

The town of Wallace, Idaho, had never seen anything like them.

WILLIAMS: The Buffalo soldiers were the first African-American men to serve as peacetime soldiers in the professional army.

They served all over the American Southwest.

They protected railroad workers and fought Indians.

You name it, they did it.

This is the first time they were ever sent to fight a fire.

And they're sent to a very white area, almost doubling the Black population of the state of Idaho.

And so when this all-Black platoon comes and sets up camp, people scoff at them, people say racist things about them.

The newspapers say they play cards and drink all night.

They say, "What can a Black man possibly know about fighting a fire?"

But it turns out, what happened with the Buffalo Soldiers is a tale that should go down in American military history.

(thunder rumbles) NARRATOR: By the second week of August, another electrical storm had more than doubled the number of fires, to 2,500.

But with thousands of fire fighters and soldiers now assembled to fight them, the Little GPs had reason to hope they might prevail, if only the fall rains would arrive in time.

♪ ♪ EGAN: The forest rangers, they're feeling pretty good.

They're feeling like, "We've tackled most of these fires.

"We've contained most of them.

"No towns have been destroyed.

No lives have been lost."

They still feel like, as Pinchot said, "Man himself could control fire."

They still feel like they're going to win this thing.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: For weeks, Ed Pulaski had been riding up and down a ridgeline in the Coeur d'Alene forest of Northern Idaho, trying to keep his men under control as they hacked fire lines through the brush.

EGAN: Pulaski is with some men up on this ridge.

One side of it is this bustling mining town of Wallace.

The other side of it is this railroad town of Avery.

Their job is to keep the thing from destroying the towns.

NARRATOR: Pulaski had 150 men under his command, and they were a ragtag group, with only a handful of experienced woodsmen among them.

After days of backbreaking labor in the intense heat, his crew was exhausted.

EGAN: Smoke comes and settles in the valleys where the towns are.

It's all around you.

The air is still, but you can't see more than 20 feet ahead of yourself.

NARRATOR: As night began to fall and in pressing need of supplies, Pulaski headed back to Wallace.

Despite everything he had done, he was still worried the town was going to burn.

♪ ♪ On the morning of August 20, after spending a few precious hours with Emma and Elsie, Pulaski reminded them of their escape plan to the reservoir, then led a mule team with supplies back up the West Fork of Placer Creek, past hillsides pockmarked with old mineshafts and abandoned tunnels, now barely visible in the thick smoke.

♪ ♪ By late afternoon, a soft breeze began to sway the tops of the white pine and spruce.

By 5:00 p.m., it had freshened to 20 miles per hour, then 30, and suddenly hurricane-force winds of 70 miles per hour were hurtling out of the west, fanning the flames of thousands of fires like an enormous bellows, merging everything into one gigantic blaze.

(fire crackling) The Big Burn had begun.

♪ ♪ EGAN: The number one goal when the thing blows up is to save the towns.

Biggest of those is Wallace.

Wallace is a town set at the bottom of a narrow valley.

So as this fusillade of giant embers comes down, one of them hits one of the newspapers there, the press solvents that are used to put out the newspaper.

And the thing goes up in a boom.

(explosions echo) It then hits a brewery.

The brewery goes up in a ball.

(glass shattering) The mayor declares martial law.

It's utter panic.

There's one train left that's going to get out.

It's going to go west to Spokane, 109 miles away.

WILLIAMS: The idea was to take the elderly, women, and children and put them on the train and have the men remain and fight the fire.

But a lot of these upstanding men tried to nudge their way onto the train.

But in most cases they were met with a soldier with a bayonet who said, "No, sir, you're going to have to stay and help fight this fire."

NARRATOR: "Words cannot depict the horror of that night," recalled one witness.

"The train whistles were screaming, "the heavy boom of falling trees, the buildings swaying and steaming from the heat."

(people shouting, bells ringing) As glowing cinders had begun to cascade around their house, Emma Pulaski had taken her daughter Elsie and fled to the rock pile by the edge of the reservoir, just as Ed had instructed.

The flames were leaping from one mountain to the other, encircling Wallace in a ring of fire.

Somewhere in that terrifying whirlwind was her husband.

"Ask God to save Daddy and his men," she told her daughter.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: The Big Burn swept eastward across the Rocky Mountains, picking up speed, consuming everything in its path.

EGAN: When this thing blew up and moved its way up into the Bitterroots and bounced around in these peaks, it became a weather system of its own.

It is a beast in search of oxygen, it is a beast in search of fuel.

♪ ♪ PYNE: The fire is drafting in on its own winds, sucking it in like a kind of hurricane.

Trees are just tossed down, jack-strawed in circles.

NARRATOR: Moving as fast as a horse could run, the fire was a cauldron of gases and explosive heat, a convection engine, pulling air into its vortex and shooting it skyward, a relentless wall of incendiary mayhem.

MacLEAN: With only a handful of experienced leaders and a handful of experienced woodsmen, you're in a catastrophe.

NARRATOR: Up in the forests above Wallace, Pulaski and his men were suddenly face-to-face with a firestorm.

♪ ♪ (fire crackling) PYNE: Ed Pulaski comes out of Wallace with his pack string of supplies, finds people scattered all over the hillside up in the ridge top where he left them, and realizes that they're in deep trouble.

NARRATOR: Confronting a wall of flame racing towards them in the gathering darkness, all thought of opposition evaporated, and the men began to panic.

Firebrands whistled through the forest.

The wind staggered them.

Huge trees came crashing down on all sides.

Then, one fire fighter remembered, "out of the smoke came Pulaski, waving his arms, "hollering, 'Come on!

Come on!

Follow me.'"

♪ ♪ EGAN: This thing is coming toward them really quickly.

People fall behind, people get injured, people get burned, people get stepped on.

Embers, giant embers are coming down.

It's like artillery coming down.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Pulaski led his 44 men through the inferno, until at last, he came to one of the old mining shafts along the creek.

"In here," he ordered, his hand on his sidearm, "everyone inside the tunnel."

(fire crackling) EGAN: They're in this tunnel and they see this wall of flames creeping toward them while they're cowering.

This fire is consuming oxygen, but to leave the cave is certain death.

They think this is the end.

NARRATOR: In desperation, Pulaski soaked some blankets in water from the floor of the cave and hung them across the entrance, but the flames seared his hands and the superheated air scorched his lungs.

Behind him, the men crammed together in the intense heat and darkness, struggling to find enough air.

PYNE: One guy says, "To hell with this, I'm getting out of here," and starts to leave.

And Pulaski pulls his pistol and threatens to shoot anybody who leaves.

♪ ♪ EGAN: Pulaski has done everything he can to save this crew.

Burned all over his face.

His hands, skin's peeled off on his hands.

And he passes out at the head of this cave.

♪ ♪ MacLEAN: Once the fire had passed the mine, some of the men started to get up and they looked at the figure of Pulaski lying at the mouth and they said, "My God, the boss is dead."

EGAN: Turns out Pulaski's not dead, he's alive.

PYNE: He was temporarily blinded.

His lungs were trashed, but he was able to get himself to his feet.

They inspected the cave.

Five had died and they had lost one man on the run to the cave.

NARRATOR: Barely able to see, Ed Pulaski managed to gather his men together, and they staggered through the still-smoldering landscape, down the mountain trail to Wallace.

♪ ♪ (fire crackling) As the fiery tempest moved past Pulaski's cave and bore down on the railroad towns to the east, Bill Greeley was desperate for information about the men under his command.

As reports trickled in across telegraph wires, the magnitude of the catastrophe began to become clear.

18 men were incinerated when they took refuge in a settler's cabin.

A crew of 28 were battling the blaze near the St. Joe River when firebrands jumped ahead of them and cut them off.

They were never seen again.

The gamblers and prostitutes of Taft refused to fight the fire, preferring instead to open up their best kegs of whiskey for one last round of debauchery.

When the eternal flames finally arrived, rangers evacuated the drunken revelers and Taft was consumed in minutes.

(train whistle blows) By the afternoon of August 20, almost 24 hours into the Big Burn, the railroad town of Avery had been successfully evacuated by the Buffalo Soldiers.

Now, the troops and the few men left in town found themselves facing a wall of steadily advancing flames.

Boarding one last train to the east, they raced across trestles already ablaze, through a furnace so hot the paint melted off the outside of the railcars.

Then the fire jumped ahead and blocked their way.

With nowhere else to go, they were forced back to Avery.

WILLIAMS: They realized, "If we can't turn this fire, "it's going to burn up not only the city, it's going to burn us up, too."

NARRATOR: At 11:00 that night, with the conflagration only half a mile away, the Buffalo Soldiers lit a backfire and held their breath.

PYNE: If you time a fire correctly and you light it in front of the main fire, then those flames from the smaller fire will be sucked in.

MacLEAN: If there's no fuel left to burn, then there's no place for this fire to go.

The forward motion of it will be stopped.

NARRATOR: "Plunging at each other like two living animals, "the flames met with a roar that must have been heard miles away," remembered one ranger.

"The tongues of fire seemed to leap up to heaven itself and after an instant's seething sank to nothingness."

♪ ♪ Miraculously, Avery was still standing.

WILLIAMS: After the town was saved, newspapers were busy interviewing everybody and one account in Avery made the comment that, "My whole attitude about the Black race has changed "as a result of what I've seen and witnessed from these fellows."

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Emma and Elsie Pulaski spent the terrifying night on the rock pile, watching Wallace burn.

As the flames receded and a feeble morning sun tried to burn through the smoke and haze, they trudged back towards town.

The entire eastern side of Wallace was a smoking ruin, but their house, to their amazement, was still standing.

Then Emma heard that a man had staggered out of the mountains with the news that Ed Pulaski and all his men had perished.

A few hours later came another report that Ed was alive, but horribly disfigured and near death.

Finally, around 10:00 in the morning, Emma looked down the road and saw a man leading someone with bandages on his head and hands.

As he walked unsteadily towards her, she recognized the burned and battered face of her husband.

Ed Pulaski had come home.

♪ ♪ EGAN: What finally muffles what's left of the Big Burn is an early season snowstorm.

Snow can happen anytime in the Rocky Mountains, but you don't expect it in the end of August, early September.

PYNE: The crews, the townsfolk, everybody just went out and just sat in the rain and the snow and let it wash them over and wash away all the grime and the fear, the horror of the days.

NARRATOR: As the atmosphere finally cleared in the Northern Rockies, the true nature of the devastation became apparent.

More than three million acres of forest had burned, and Greeley estimated that a billion dollars worth of timber had been lost.

The winds were so strong, entire sections of the forest had been flattened, huge trees spread out like kindling.

Soot from the fires darkened sunsets as far away as Boston, and a layer of ash blackened the ice in Greenland.

The human toll was equally appalling.

One of the startling things that happened in 1910 were all the dead fire fighters.

There were 78 during the Big Blowup and this had never happened before.

They had no idea what to do.

There's no worker's comp.

There's nothing to pay for their expenses.

There's no burial money.

They simply don't know what to do.

EGAN: The survivors go to these hospitals and they patch them up.

But what happens afterwards is horrible.

One of them commits suicide.

Others die months or a few years later and they weren't even credited as part of the official casualty toll because their lungs were so badly compromised by how much smoke they breathed in.

They die at 28, 29 years old from the smoke of the Big Burn, which kills them six months after the fact.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Before the smoke had even cleared from the mountains, the debate over the lessons of the Big Burn began.

EGAN: Gifford Pinchot has two reactions to it.

The first thing is horror, because remember, he said this hubristic thing saying man himself could control fire.

Nature has proved him utterly wrong.

So he's horrified by this thing.

He's horrified by the loss of life.

But he also has a second reaction.

And this is indicative of all great political figures.

Pinchot uses the fire as part of a narrative about American heroes, that these forest rangers gave their lives, risked everything for public land, for national forests.

And all the newspapers write these stories.

It's one of the first times in our history that fire fighters join the pantheon of American heroes.

PYNE: The critics of the Forest Service say, "Look, you guys had everything you wanted.

"It didn't work.

We knew it wouldn't work, so you lost."

But Pinchot argued that, "No, we just didn't have enough "to really give it a full test.

"And we need to honor those who died by seeing their vision completed."

♪ ♪ EGAN: But what should have been their lowest ebb turns out to be their creation myth.

So much public support arises for the Forest Service and the national forests that it has the effect of pushing public policy.

What had been a reluctant Congress now gives the Forest Service the resources it needs, doubling the budget, and eventually creates national forests in the East-- in Pennsylvania, Mississippi, Virginia.

NARRATOR: As the agency grew under the stewardship of men like William Greeley, putting out fires became almost an institutional obsession.

(airplane engine roars) EGAN: Nothing affects the culture of the Forest Service more than this fire.

They become sort of a municipal fire service of national forests.

Only you can prevent forest fires.

NARRATOR: In the decades after the Big Burn, the agency's uncompromising stand on fire would serve the Forest Service well, but its impact on the national forests would be fraught with unintended consequences.

MILLER: I think the fundamental dilemma with the fire suppression policy that Pinchot advocated was in the end, it was the wrong policy for the land.

It may have been the right policy for the agency, but it's the wrong policy for the environment.

KODAS: Fighting fires in the wilderness was not only futile, but it was really not healthy for the forest.

If you have a landscape that normally would burn every 20 years and you put out every fire in that forest for a hundred years, you now have five times more fuel in that forest than you normally would.

The medicine that we were giving was worse than the disease.

EGAN: By putting out every fire for a hundred years, they created, indirectly, what are now some of the greatest wildfires.

♪ ♪ But imagine now if this fire had not happened they might have killed the Forest Service.

And with it would have gone the idea that's so embraced by a majority of Americans today, that we have more than 500 million acres that is all of ours, that belongs to each of us.

By saving the fledgling idea of conservation, then only a few years old, this fire did save a larger part of America.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: In the end, Ed Pulaski could never escape the Big Burn.

He lived on with Emma in Wallace, remaining what he had always been, a quiet man who loved the mountains of the West.

Crippled by the flames that had seared his eyes and lungs, he kept on working for the Forest Service until 1929, stubbornly petitioning the government for compensation for his wounds and for money to care for the simple graves of those who had fallen.

He also never stopped using his hands and crafted a tool with a hoe on one end and an ax on the other.

It was so perfectly designed that fire fighters around the world never again did battle without what came to be known as a Pulaski by their side.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪

Preview: S27 Ep4 | 30s | In 1910 the largest fire in U.S. history burned over 3 million acres. Premiering Feb 3. (30s)

Clip: S27 Ep4 | 2m 58s | In the early 1900s, timber was an essential US product. Premieres Feb. 3 on PBS (2m 58s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep4 | 7m 59s | In 1910 the largest fire in U.S. history burned over three million acres. (7m 59s)

Clip: S27 Ep4 | 2m 54s | Fire was essential to the survival of the new US Forest Service. Premieres Feb. 3 on PBS. (2m 54s)

Clip: S27 Ep4 | 2m 35s | Roosevelt and Pinchot make a plan to save America's wilderness. Premieres Feb. 3 on PBS. (2m 35s)

Clip: S27 Ep4 | 2m 19s | Firefighters are regaled as heroes for the first time in America. Premieres Feb. 3 on PBS. (2m 19s)

Clip: S27 Ep4 | 1m 45s | In 1910 the U.S. Forest Service was desperately understaffed. Premieres Feb. 3 on PBS. (1m 45s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

For Season 27 of American Experience, exclusive corporate funding is provided by Liberty Mutual Insurance, major funding by The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, funding from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting...